There has been a strong Italian presence in Rochester, New York for over 150 years, with Irish and German being the other two dominant immigrant cultures. The first Italian immigrant to Rochester arrived in 1860.

As this ethnic population grew, it migrated to and settled in the neighborhood along the streets of what is now known as Lyell Avenue. Rochester’s city historian Blake F. McKelvey documented references to the area’s being called “Rochester’s Little Italy” going back to 1906.

This area of Rochester has a much-neglected past. It has chronic serious crime issues, prostitution and ever-present drug dealing. Property values are lower than other locations in the community and it has one of the higher levels of per capita poverty in the City.

Blanketing all of these issues is the lack of any group or organization to be able to gain traction with municipal officials in the same way as other part of the city have been able to do.

While other parts of the City have been the focus of major economic efforts in years past, the Lyell Avenue corridor has not shared in those efforts. Significant work was done to the business corridor of Main Street in the late 1980’s – early 1990’s, major economic zones have come and gone for projects such as the never-realized Renaissance Center Cultural and Performing Arts center and Rochester’s short-lived Fast Ferry project. (That project at least did bring major improvements to the State Street and Lake Avenue as well as a resurgence in interest in the Charlotte neighborhood.)

Even the recent Focused Investment Strategy (FIS) program overlooked this area of the city, instead focusing on the Marketview Heights / Dewey Driving Park / Beechwood and Jefferson Avenue neighborhoods.

There have several efforts in the past to address certain critical security issues on Lyell Ave. A NET office (Neighborhood Empowerment Team) was created on Lyell as a liaison for City Hall and Police working with the neighborhood, and a HUD sponsored commercial façade improvement program was offered in the 1990’s but that program had little or no impact to the community. Even the construction of two sports stadium venues—Frontier Field baseball and Capelli soccer—in nearby locations have failed to bring any impetus to improving this area.

There have several efforts in the past to address certain critical security issues on Lyell Ave. A NET office (Neighborhood Empowerment Team) was created on Lyell as a liaison for City Hall and Police working with the neighborhood, and a HUD sponsored commercial façade improvement program was offered in the 1990’s but that program had little or no impact to the community. Even the construction of two sports stadium venues—Frontier Field baseball and Capelli soccer—in nearby locations have failed to bring any impetus to improving this area.

This is not meant to paint the Lyell Avenue area as one of lost hope. On the contrary, there are many in this area who are committed to their business and homes that want to benefit from what they see going on in other parts of their community. It is for these people that the Little Italy Historic District was envisioned.

So…what to do? How does this worthy and historic area of the city improve its place in the community? Many are coming to believe that the missing piece in being able to move Lyell Avenue’s future forward is the creation of an identity that the surrounding businesses, citizens, landlords and tenants can rally around.

So…what to do? How does this worthy and historic area of the city improve its place in the community? Many are coming to believe that the missing piece in being able to move Lyell Avenue’s future forward is the creation of an identity that the surrounding businesses, citizens, landlords and tenants can rally around.

Such an entity would draw on the historic ethnic strength of the area, its position as the primary western gateway to the City, and its proximity to the present resurgence of interest in urban live / work / play areas now undergoing transformations in the High Falls and City Center areas.

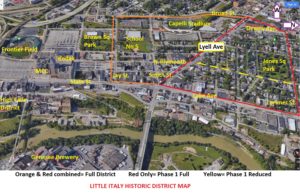

As a result, it’s been proposed that a Little Italy historic district be created for the Lyell Avenue corridor and Jones Square Park neighborhoods. This historic designation would provide a framework for the local commercial and residential communities to use while building a sense of identity that is heretofore lacking for Lyell Avenue.

As a result, it’s been proposed that a Little Italy historic district be created for the Lyell Avenue corridor and Jones Square Park neighborhoods. This historic designation would provide a framework for the local commercial and residential communities to use while building a sense of identity that is heretofore lacking for Lyell Avenue.

It would be heralded by the present Little Italy Neighborhood Association, which already has a significant interest in Italian culture through its many connections to the Rochester community, such as being the sponsor of the yearly Little Italy Festival. The festival is a very inclusive neighborhood celebration, which features and promotes not only the Italian culture and its traditions, but also the food and music of all cultures that reside in the neighborhood.

Of course, as the 3Re Strategy (repurpose, renew, reconnect) described here makes obvious, it’s extremely hard to revitalize a downtown or a historic district if one doesn’t pay attention to the connections. Nothing lives in isolation. Many Main Street-type revitalization efforts have failed because the leaders couldn’t get their heads out of the downtown.

Making a district more attractive is a good first step. But if the customers one seeks to attract must walk or drive through an unappealing and/or dangerous area to get there, it probably won’t be enough.

The most successful downtown revitalization initiatives often include a corridor revitalization initiative. It’s similar to the reason a retailer will make their store’s entrance appealing and easily accessible, rather than just focusing on the interior. The Lyell Avenue corridor is the major western arterial road for Rochester. It is also the primary gateway roadway artery into Rochester.

In a private communication with me (Storm Cunningham), Little Italy Neighborhood Association President Silvano D. Orsi said “We believe revitalizing the Lyell Avenue Gateway Corridor is important to the success of those nearby projects, and that this primary artery into the city will feed those projects with the vital tourism that they expect to sustain them, primarily coming from the west side of the City, and from the Buffalo, Niagara Falls, and very wealthy nearby Ontario region, which includes major cities like Toronto, Mississauga and London.”

In the case of Rochester’s Little Italy, the Lyell Avenue Gateway Corridor corridor is the obvious target for renovation. The Lyell area is one of the nation’s poorest neighborhoods, where one in every two children lives below the poverty line. The area has been neglected for nearly three decades, with little public or private investment since the soccer stadium was built in 2006.

But the scope of that corridor renovation is crucially important. Too large, and it’s unaffordable. Too small, and the Little Italy Historic District could die from insufficient inflows.

Good connectivity means effectively connecting the Little Italy area to other revitalized or revitalizing areas of the city, such as the ROC the Riverway project (described earlier here and here in REVITALIZATION.) Coordination and integration of multiple revitalization projects is one of the most common weaknesses I’ve encountered in my two decades of work in the field.

I got to witness the wasted resources and civic discouragement of poor integration first-hand during the 15 years I spent in the Tampa Bay area in the late 70s and throughout the 80s. Like so many cities, Tampa back then had no cohesive revitalization strategy, and no one assigned to fulfilling a long-term vision and strategy. Here’s an excerpt from a REVITALIZATION article I wrote in the July 1, 2017 issue:

“Downtown Tampa in 1980 had been in decline for decades. The 2.5-mile Riverwalk strings all this revitalization together. It took six mayors and 40 years, but the RiverWalk has opened up public access to the waterfront, connected the big public projects, and led to something new in downtown Tampa: a plethora of pedestrians and bicyclists–shoppers, tourists, and downtown residents–all enjoying the beautiful, long-ignored Hillsborough River.

As a former long-term resident of the Tampa Bay area, I’m delighted that Tampa downtown revitalization efforts are finally paying off. But I think they did it backwards: completing the RiverWalk should probably have been the first element of their strategy.

Reconnecting the downtown to the river in such a grand manner would have inspired tremendous confidence in the downtown’s future, attracting private investment far sooner. Instead, they never had a real strategy and comprehensive renewal process.

As a result, they went through two decades of stop-start redevelopment, leaving a string of failed projects along the way. Each project was done in isolation, and was usually dead or dying by the time the next project started (such as Harbor Island). The lovely new convention center was built, but almost went out of business due to a lack of nearby hotel capacity (since remedied).

The ambitious Channelside waterfront redevelopment thrived for a while, but went into decline, in part because the new trolley serving it wasn’t free, and wasn’t frequent enough. A downtown pedestrian mall similarly was vibrant while it was new, and the went into decline, mostly due to a paucity of downtown residents.

A Riverwalk would also have attracted downtown residents and tourists (shoppers), providing the customers that so many bankrupted downtown retailers and restaurants needed in those days. I know they’d probably say ‘but we didn’t have the money in those days!’. That’s the universal excuse for bad planning. The key is to find the best possible strategy, and find a way to fund it. Put the pain up front, rather than spreading it over decades.” [end of excerpt] Anyway, I’m glad Tampa had the perseverance to get past those tough times. Since every revitalization effort involves a lot of learning and trial-and-error, perseverance is often the key ingredients.”

Business owners are encouraged to fly the flags of their families’ native countries in a celebration of diversity.

Hopefully, the creation of a Little Italy Historic District in Rochester will be accompanied by a strategy and process that includes the revitalization of this entire corridor, and not just the small part of it within the historic district. I’d hate to see a repeat of Tampa’s experience.

Regarding displacement worries on the part of current residents of the area, Silvano said “we really make it a point to be very inclusive in our efforts, and rather than rebuild an ‘Italian neighborhood’ or gentrify the area, we are hoping to transform the area into a ‘hip’ and historic multi-cultural destination.”

“The goal is to have no one displaced, while creating a modern, sustainable, 21st Century urban neighborhood. This serves to attract new investment to the area, primarily in the housing, retail, food and tourism sectors. We believe this will, in turn, create jobs for area residents, helping to alleviate the area’s nearly-unbearable crime and poverty,” he continued.

Orsi explained that last point in a bit more detail: “One in every two children residing in the area with their families lives below the poverty line. We aim to change that, modelling it on San Diego Little Italy’s very successful “community benefit district” (CBD) model. I have worked closely with Marco LiMandri, CEO of New City America and CAO of Little Italy San Diego to write enabling legislation. This would enable New York State to create and implement Community Benefit Districts and BID’s more easily. Our Little Italy Historic District in Rochester hopes to be the pilot program for this new state CBD model.”

The Little Italy Neighborhood Association has applied for a $1 million grant from New York’s Upstate Revitalization Initiative and hopes to match it with at least another million if they win it.

On August 26, 2018, the association unveiled their renderings of the revitalized neighborhood. Local resident Tommie Parker said in response, “The vision is absolutely beautiful. Oh my God, I just got chills when I saw the new vision and hope for Lyell Avenue.”

The historic designation provides many benefits:

- It elevates the impression of the area by connoting a recognized connection of importance to the areas past;

- It provides a means to coordinate and organize a higher standard of outward appearance for the structures that create and define the public realm; and

- It provides the possibility of tax credits that can be applied to renovations of qualified buildings to help offset those costs while creating a more unified appearance for the streetscapes.

But Rochester should be careful to avoid one of the pitfalls of historic districts: sometimes the district’s governing body becomes so rigid that they kill exactly what they’re trying to save. They don’t allow anything new, even when its modern architecture complements the historic fabric. The right new building can actually enhance the charm and beauty of an old one.

Or, when they do build something new, they require that the structure use the same architectural vernacular as the historic structures. This creates a phony “Disneylandish” feel. When visitors can’t tell a new building from an old one, it diminishes the value of the genuine heritage. It also gives developers an excuse to demolish what’s old, since they can just create an imitation in its place.

On August 31, 2018, the Little Italy Neighborhood Association (LINA) requested a round-table meeting and discussion with Lovely Warren, the Mayor of Rochester, plus the City Council, county leaders, state officials and Lyell area community leaders. The goal is to “form a leadership group that will work together to develop and implement a long-term plan for the now vacant Marina Auto Stadium, and for revitalization of the troubled and unattractive Lyell Avenue Gateway Corridor.”

LINA has requested that the Mayor lead the round-table discussion, hoping to gather vital input from local community leaders and officials elected to represent the Lyell Avenue area.

Meanwhile, the City of Rochester would undertake its new and parallel $100,000 “commercial corridor study” across the city’s many distressed commercial corridors.

Improving the arteries that feed visitors into the city center, will improve the chances of success for adjacent projects like ROC the Riverway. They are modelling their Little Italy Historic District on the very successful San Diego Little Italy.

Another important initiative for the Lyell area is the transformation and development of the now-vacant former Tent City Outlet building into the $23 million Gardiner Mill Apartments.

Winn Development, as well as Christa Construction and Depaul Development, have all expressed interest in coverting the building into a mixed-use facility, which would include affordable and market-rate apartments, and a first floor “retail market” similar to the one in the Bronx Little Italy, which would provide much need access to fresh food for area residents.

There are currently no nearby fresh vegetable and food markets in this area of the Lyell corridor.

Refurbishing the Tent City building to include a fresh food and retail market on the first floor could be a catalyst for further revitalization and redevelopment in the Lyell corridor / Little Italy area. This could bring more residents, tourism and purchasing dollars to the area. Creation of a new “Piazza Famiglia” (family piazza) is also part of the building’s intended new design, whether with Winn Development or other developers.

The building has been placed on the Landmark Society of WNY‘s “Five to Revive” list, and with the Landmark Society’s advocacy, the building’s owner may be seeking its historic designation via a submission and request to the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) in Albany, and the National Register of Historic Places in Washington, DC. The Flat Iron building, located just down the street, might do likewise, so that the two buildings may act as historic book-ends of sorts, marking the Little Italy historic district’s East and West entrances.

Silvano D. Orsi (r) presents NY Gov. Andrew Cuomo with traditional Italian Easter bread, baked by Silvano’s 86-year-old mother.

(March 31, 2018, Executive Mansion, Albany.)

An initial planning and feasibility study completed last year by local Rochester area architectural firm Pardi Partnership Architects indicates that the Lyell area requires urgent attention, and a comprehensive, long term, economic development and public safety plan. They say it also needs major public realm improvements, in order to trigger private sector investment, primarily in the housing, retail, food and tourism sectors.

The Pardi Firm study, which cost $6,600, was paid for by LINA President Silvano Orsi from his own personal funds, as a further investment in the neighborhood and Lyell area revitalization project.

Orsi concluded, “We look forward to meeting with area officials and community leaders, and to forming a core group of partners, responsible for revitalizing the Lyell Avenue Gateway Corridor. After decades of neglect and unbearable crime, we believe the time has come now, to develop a long-term plan for the Lyell area, which will help transform the Lyell Gateway and its Little Italy District, into a safe and vibrant destination place, for the enjoyment and benefit of the entire community.”

Featured photo of Rochester’s Littly Italy courtesy of Silvano D. Orsi.