Does your city or region have some efforts for revitalization (healing),

and others for resilience (prevention)? That’s inefficient, and likely to fail.

They can and should be achieved together. RECONOMICS shows you how.

If you have ANY role in improving your local future, you need to read this.

After 20 years as an author, publisher, speaker, trainer and advisor on regenerative economics worldwide, I offer this illustrated, online version of my third book (buy it here) to help your government, charity or company boost economic, environmental and social health in regions and communities.

“RECONOMICS: The Path to Resilient Prosperity” is a guide to healing economies, societies and nature for policymakers, real estate investors and entrepreneurs. What it reveals can easily double the ROI (revitalization on investment) of your redevelopment, renewal and climate adaptation efforts.

by Storm Cunningham, Publisher, REVITALIZATION Last updated: November 14, 2021

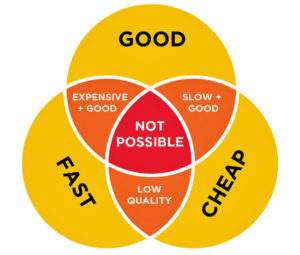

Why didn’t your downtown beautification, historic restoration or mixed-use redevelopment revive your community?

Probably because you lacked a regenerative strategy and a proven process to fully fund and implement revitalization.

It’s common for places to receive funding for renewal or resilience. It’s rare for them to know how to leverage it.

“RECONOMICS should be mandatory reading for all Mayors, Chief Executives and Directors of Planning in cities and regions.”

– Rick Finc, Principal, RFA Development Planning, Edinburgh, Scotland

“RECONOMICS is very concentrated, highly sophisticated, and stunningly accurate.”

– Merrit Drucker, Clean & Green Coordinator at Anacostia Waterfront Trust, Washington, DC

“Storm Cunningham’s RECONOMICS transformed our latest project, which uses his 3Re strategy.”

– Doumafis F. Lafontant, Director, Lower Roxbury Coalition, Boston, Massachusetts

“RECONOMICS is a must-read for every mayor, resilience activist, planning commissioner and urban redevelopment professional who has been frustrated in their attempts to revitalize a place. It succinctly describes why most revitalization plans fail,

analyzes what’s missing, and provides a simple, easy-to-follow strategic process for success.”

– Kevin L. Maevers, D.Mgmt., AICP; President, Arivitas Strategies, LLC, La Quinta, California;

Vice Director of Policy, IES, California Chapter, American Planning Association

“RECONOMICS hits the nail on the head!”

– Nalin Seneviratne, Director of City Centre Development, Sheffield City Council, Sheffield, England

“Storm Cunningham’s RECONOMICS Process raises the bar for community and regional revitalization. It’s a powerful package, succinctly capturing the process that we have doggedly tried to identify over time, not always knowing the next step.

The RECONOMICS Process brings a holistic dimension to redevelopment, inextricably linking vision and task.”

– Eric Bonham, P.Eng, Board member of the Partnership for Water Sustainability in British Columbia

Former Director, BC Ministry of Environment and BC Ministry of Municipal Affairs

“Storm Cunningham is so far ahead of the community revitalization game, I’m in awe.”

– Sarah Sieloff, Executive Director, Center for Creative Land Recycling (September 2019)

A strategic renewal process is how a place revitalizes when it has no money,

and how it revitalizes faster, better, safer and more efficiently when it has funding.

Only a strategic renewal process can integrate economic growth with resilience to create Resilient Prosperity.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE - The Holy Grail: A reliable process for fixing economies, societies, nature & climate together.

On the last day of 2019, exactly 3 weeks before this book was published, the lights went out and ferry service stopped in the town of Little Bay Islands, Nova Scotia. Permanently.

This picturesque array of brightly-painted fishing houses on narrow streets on Canada’s North Atlantic coast is dead: purposely abandoned, as all 51 residents left at the same time.

Once a thriving fishing village, it was killed by the decline of the local fishery. This led to the loss of job opportunities, which led to the loss of young people, which led to the loss of confidence in the community’s future. In 2019, residents voted in favor of resettlement elsewhere.

They once had prosperity, but it wasn’t resilient prosperity. If the fishery had been restored, that would have restored jobs, young people and confidence in the future in one fell swoop. That’s how a restoration economy works.

Thousands of communities around the world have, for decades, been on a “Holy Grail” quest without knowing it. All of them want two things: 1) resilient prosperity and 2) an efficient, reliable process to produce it.

- Resilient Prosperity: No matter whether a place is thriving or distressed, all want a higher quality of life and a more vibrant, inclusive economy: in other words, revitalization. And they want it to last in the face of national economic cycles, political turmoil and the climate crisis. In other words, resilience. Thus, the universal goal is “resilient prosperity” (though few have clarified their thinking enough to use that phrase).

- Strategic Process: Every public leader knows that the reliable production of anything requires a process, whether it’s a factory producing air conditioners, a tailor producing clothing or a tree producing nuts, wood and oxygen. They also know, deep down, that they have no real strategy or reliable process for producing either revitalization or resilience in their community (though few would acknowledge it).

I’ve spent the past 20 years leading workshops, keynoting summits and consulting in planning sessions at urban and rural places worldwide. All of these events were focused on some aspect of creating revitalization or resilience. Most of those events had other speakers who recounted their on-the-ground efforts and lessons learned. I’ve thus spent the past two decades researching commonalities: what’s usually present in the successes, and what’s usually missing in the failures?

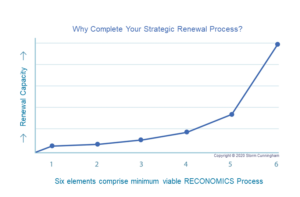

I’ve boiled it down to six elements. Each of them individually increases the likelihood of success. The more of them you have, the more likely you are to succeed. All of them together creates a process that’s far more dynamic than the sum of its parts. If you’re a community leader, you can thus start assembling the locally-missing pieces of the process in whatever order makes sense—and is least disruptive—for your situation.

Many mayors, governors and presidents have intuitively tried to form such a process. Most had two or three of the six elements. Some had four or five: none had all. Even in those few places that came close, the elements didn’t form a process. They were disjointed—usually spread over a long period of time—and had no logical order. In other words, they had the body parts, but no fully-functional body. Thus, they often went nowhere…or not very far. No process = no progress.

I have encountered a few effective renewal processes, but they only address very limited scopes—such as revitalizing downtowns, redeveloping old industrial sites or restoring wetlands—and for very specific kinds of assets, such as brownfields, infrastructure or heritage. Processes for regenerating entire communities or regions seem to be entirely missing.

The goal of creating resilient prosperity for all is obviously of vital importance. So why are efforts to create a process for revitalization or resilience so haphazard? Two reasons: 1) They didn’t consciously know that creating a process was what they were trying to do; and 2) They didn’t have an ideal process template to shoot for. It’s been like trying to assemble a jigsaw puzzle without knowing what it was supposed to look like when finished.

– Kurt Lewin, German-American psychologist.

That’s the focus of this book: to present that ideal process for producing resilient prosperity. Like all good processes, it can be adapted to local goals and constraints: it’s the basic flow that’s of crucial importance, not the specific activities that ensue. Most newly-established processes of any kind will accrue elements as they mature. The key is to put the right bones in place initially: the flesh can develop over time. Thus, the process recommended here is a “minimum viable process”: you can add to it if necessary, but deleting even a single element will drastically reduce its effectiveness.

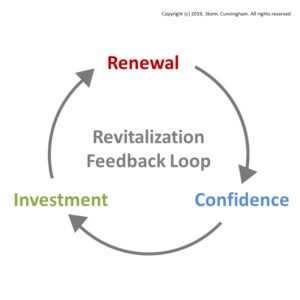

Without a process to connect to, projects tend to wither on the vine from lack of support. Or, projects die because they expend too many resources reinventing functions that should have been provided by a local renewal process. Or, lacking a local “flywheel,” projects don’t add momentum, so confidence in a better future doesn’t increase; residents and employers leave and new ones aren’t attracted as a result.

Of course, it isn’t just lack of process that stymies renewal efforts. The list of potential roadblocks is endless: defeatist public attitudes; empty public coffers; unenlightened leadership, etc. But there’s one obstacle that’s as universal as the lack of process: the “assumptions trap”.

People assume that their fellow stakeholders share their definition of “revitalization” or “resilience”…that they’re all heading in the same direction. They assume that their leadership has had some training in the art of renewal: that they know how to make it happen. They assume that someone is in charge of creating a better future. In most places, none of those assumptions is correct. We’ll dive into those problems—and their solutions—later: this is just the Preface.

Why am I the one who’s writing this book, as opposed to someone famous, powerful…or at least good-looking? Because, as a lifelong world traveler, nature lover, and fan of cities with unique cultures and beautiful heritage, I’m frequently horrified when returning to my favorite places, only to find them degraded or destroyed. I seldom SCUBA or snorkel any more: the barren, lifeless sea floors found all around the planet are just too depressing. I’m old enough to remember the vibrant beauty and rich diversity of just four decades ago.

Badly planned (or unplanned) urban growth and poorly-regulated (or unregulated) natural resource extraction—plus the climate crisis—are the usual culprits. But in the 90s, I started perceiving a glimmer of hope. I increasingly encountered places where governments, businesses, and non-profits were restoring nature, restoring heritage, restoring health and beauty, and revitalizing economies.

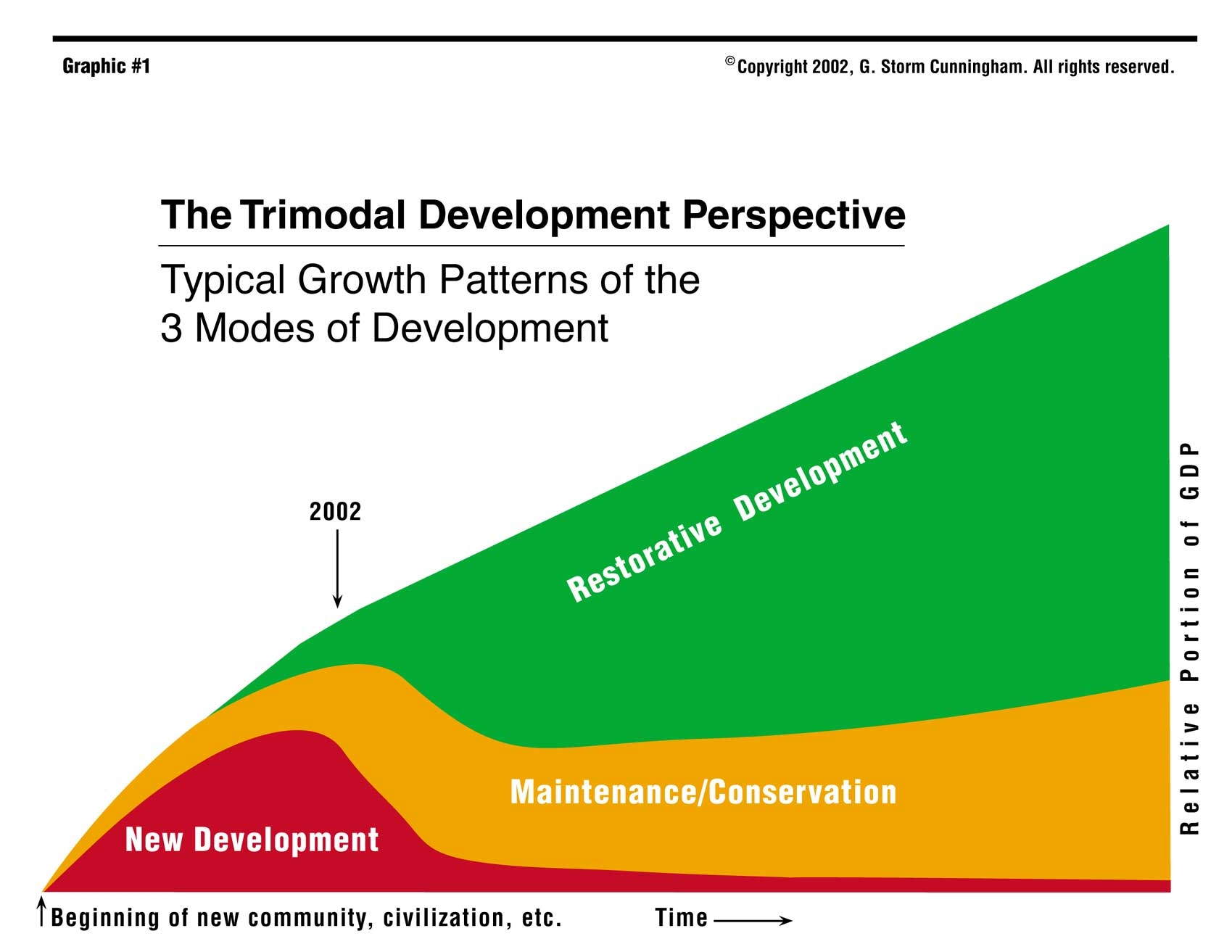

I decided to champion this nascent trend, starting out with great enthusiasm and confidence when my first book, The Restoration Economy (Berrett Koehler), was published in 2002. It was the first book to document the rise of a vast global trend I dubbed “restorative development”. It described eight huge, fast-growing industries and disciplines that are renewing various aspects of our natural, built and socioeconomic environments.

but “how do we become the best for the world?””

– Uffe Albaek, Founder, The Kaos Pilots.

Some were new industries, like brownfields remediation/redevelopment, which now accounts for some $7 billion in annual activity in the U.S. alone. Some were new sciences, like restoration ecology. Others, such as restoring/reusing historic buildings—or renewing/replacing aging infrastructure—have been around for as long as humankind has been building cities. But even those older forms of renewal have expanded dramatically over the past 20 years, with far more growth to come as a tipping point from degeneration to regeneration nears.

I had found my niche. I’m earning a living I love, being paid well—sometimes over $12,000 for a 60-minute talk—to travel the world as an author, speaker and consultant. I’m not getting rich, but life is good.

One of my more-recent clients, the Partnership for Water Sustainability in British Columbia (PWSBC) recently showed itself to be on the leading edge of watershed restoration. How? By focusing a significant portion of their April 2-4, 2019 conference in Parksville (Vancouver Island) on the subject of regional revitalization.

I was asked to deliver most of that content to an audience that largely comprised Streamkeepers and other technical experts who do the on-the-ground work of restoring watersheds. One might wonder what someone who spends their days moving dirt, reducing pollution, removing invasive species and restoring native species might have in learning how places revitalize themselves socially and economically.

The short answer is that such understanding is the key to attracting more funding and more support (citizen and political) for their watershed projects. If they better-understand how their work contributes to economic renewal and quality of life, they will be far more persuasive when it comes time to justify their budgets. And if they better-understand the process of revitalization, they will know where best to insert themselves into local decision-making.

The major flaw in that last statement is that most places don’t actually have a renewal process. So experts, asset owners and other stakeholders have no efficient way to insert themselves into local regeneration. As a result, they just tend to do a lot of isolated projects, hoping that larger-scale revitalization (or resilience) magically appears as a reward for their hard work. But hope is not a strategy.

Most people who are traditionally seen as being responsible for creating community revitalization—mayors, economic developers, private developers, planners, etc.—don’t actually know how to think about revitalization. Most of them tend to think of it as a goal, rather than as a process. As a result, they have “magical” expectations: they assume that revitalization will automatically emerge if they just keep doing more of whatever it is they know how to do:

- If they’re a mayor, they try to lead the way to revitalization via vision and deal-making;

- If they’re developers, they try to build their way to revitalization;

- If they’re architects or engineers, they try to design their way to revitalization;

- If they’re planners, they write plans as a way to revitalization;

- If they ‘re economics developers, they try to incentivize their way to revitalization;

- If they’re activists, they try to organize or sue their way to revitalization; and

- If they’re ecologists or watershed managers, they try to restore their way to revitalization.

All are doing their best with what they have, but is it enough? Only rarely… when stars align and the right things happen in the right order in the right place at the right time. But we’re talking about the future of the place, and everyone in it. Is hoping for the best the best we can do?

A stream on Vancouver Island, BC with the restored, historic Kinsol Trestle in the background.

Photo by Storm Cunningham.

This lack of process is a wonderful career growth opportunity for those involved in reviving almost anything…whether watersheds, brownfields, heritage, infrastructure, workforce, housing, etc. Being the one at the table who actually understands how to structure local activities to increase the ROI (revitalization on investment) positions you for a real leadership role in your community or region.

The folks who attended any of the three talks and workshops I did for those watershed leaders in British Columbia in April of 2019 now have a greater appreciation of process. If you weren’t there—or at any of my other presentations around the world in recent years—here’s a quick recap of what I told them about creating regional revitalization and resilience.

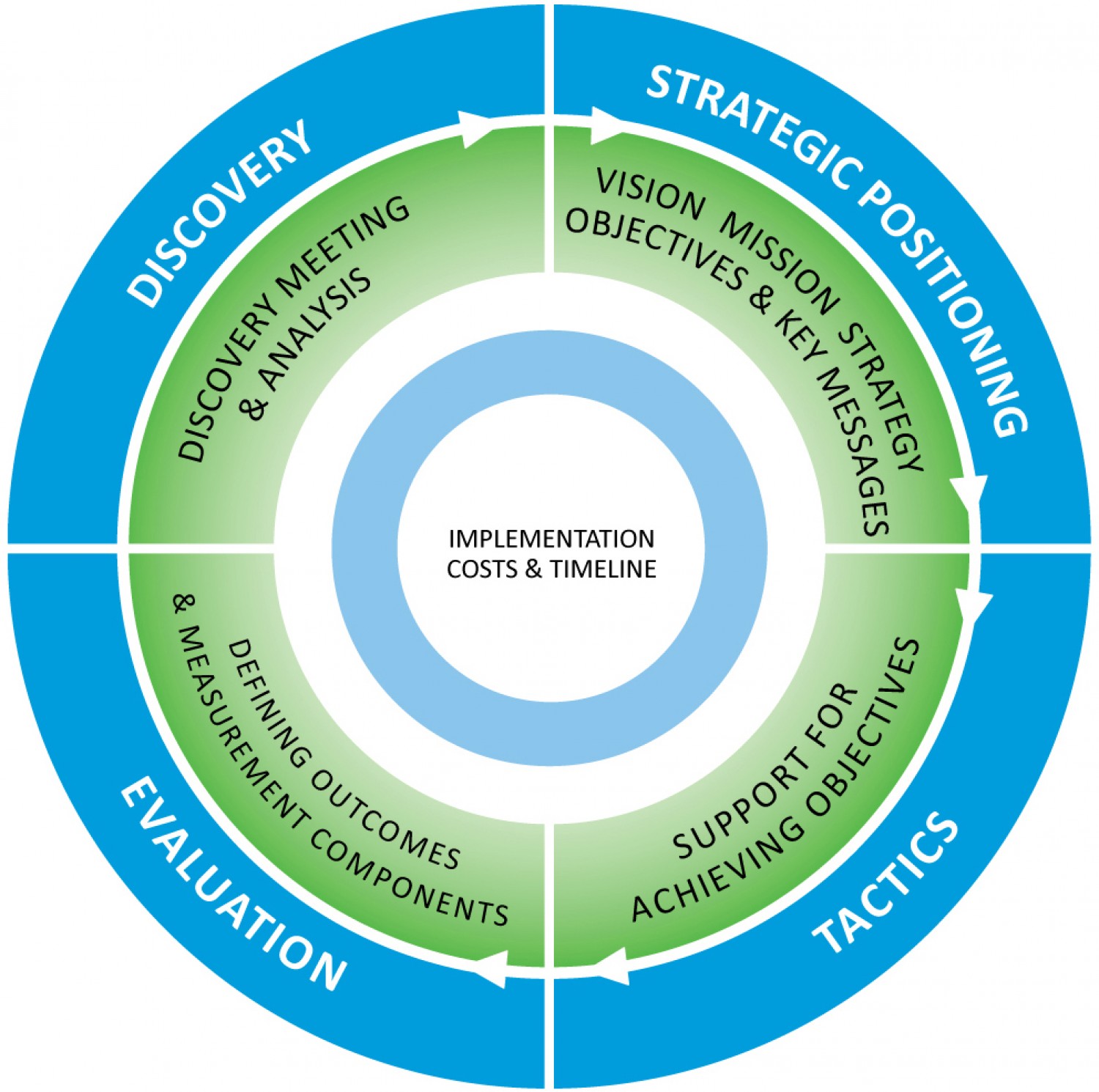

The first step is to create an ongoing revitalization (or resilience) program, which constantly initiates, perpetuates, evaluates and adjusts local renewal efforts. Without an ongoing program, you have little chance of building momentum, which—as mentioned earlier—is essential to increasing confidence in the future of the place, in order to attract and retain residents, employers and funding.

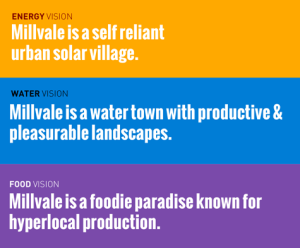

The first job of that program (which could be housed by a foundation or non-profit organization) is to facilitate a regenerative vision for the future, along with a “renewable asset” map that reveals opportunities to achieve that vision. The second step is to create a regenerative strategy to overcomes obstacles to achieving that vision. Next, it’s best to do some regenerative policymaking, adding support for that strategy (via zoning, codes, ordinances, etc.) while removing policies that undermine it.

Once all of that is done, it’s time to move into action. Recruiting public and private partners into your program is the next step. This provides the human, financial and physical (such as properties) resources needed to do regenerative projects, which are the “final” step of the process. I put “final” in quotes because regeneration is a never-ending activity, so the process is circular, not linear. A place that is no longer revitalizing is devitalizing. Stasis is usually an illusion that masks decline.

Armed with an understanding of the above, those BC Streamkeepers and other watershed heroes are no longer operating in a silo, totally dependent on others to champion, fund and support their work. They are far more capable of being their own champions when face-to-face with funders, politicians and stakeholders.

And, they are better able to identify where in the revitalization / resilience process they or their organization should be engaged, in order to be most effective: the program, the vision, the strategy, the policymaking, the partnering or the projects. But let’s back up a bit, for context.

And, they are better able to identify where in the revitalization / resilience process they or their organization should be engaged, in order to be most effective: the program, the vision, the strategy, the policymaking, the partnering or the projects. But let’s back up a bit, for context.

I started writing that first book, The Restoration Economy way back in 1996. Many now-huge regenerative disciplines and industries were just emerging then.

I’ve been enormously gratified to hear from regenerative leaders worldwide, who credit their reading of that 2002 book with the genesis of their career and/or organization.

It apparently helped advance many of today’s regenerative trends, such as resilience, regenerative agriculture (it had a whole chapter on this now-hot trend), circular economies, carbon-negative (climate restoration), heritage renewal, integrated disaster reconstruction, etc. As a result, many leaders who normally would have defaulted to the failed paradigms of “green” and “sustainable”—which helped create today’s global crises by not yielding effective solutions—are now defaulting to restoration. For example, in the November 2019 issue of Fast Company magazine, Kat Taylor, CEO of Beneficial State Bank in Oakland, California said that we need a “new economy that’s fully inclusive, racially and gender just, and environmentally restorative.”

In 2008, my second book, Rewealth, was published by McGraw-Hill.

Whereas The Restoration Economy documented—and created an eight-sector taxonomy for—the broad variety of regenerative projects, Rewealth documented the best practices for turning those projects into the desired outcome of local revitalization: economic growth coupled with enhanced quality of life. You’ll find a brief overview of both books’ key concepts in Chapter 2.

Whereas The Restoration Economy documented—and created an eight-sector taxonomy for—the broad variety of regenerative projects, Rewealth documented the best practices for turning those projects into the desired outcome of local revitalization: economic growth coupled with enhanced quality of life. You’ll find a brief overview of both books’ key concepts in Chapter 2.

Here in RECONOMICS, I reveal the most important and useful insights I’ve gained in the 23 years I’ve spent researching, writing about and teaching this subject.

The title of this book derives from reconomics: a new framework and process for revitalizing economies and making them more resilient. Resilient prosperity, in other words. “Economies”, in this case, includes every scale: national, regional, community, organizational, and even personal.

Communities all around the planet are suffering from economic, social and/or environmental decline. Some due to technological shifts, and others to economic shifts. Some due to local disturbance like war, and others due to global factors like changing weather patterns and sea level rise. In other words, tens of thousands of communities need to produce some form of revitalization. And they don’t just want a brief burst of revitalization: they want resilience as well. The speed of their renewal cycle will be determined locally, depending on a combination of urgency of need, size of the community/region, and management capacity.

Adding a reliable, replicable process for community and regional improvement is the first truly fundamental change in local governance in decades. I specified “public” leaders above because successful corporate leaders are all about process. They know that production and process are virtually synonymous: one simply cannot get the former with the latter. It doesn’t matter whether they are producing vacuum cleaners or marmalade: without a process, there’s no production.

In retrospect, it seems I’ve always been process-oriented. Here’s a truly mundane example. When the personal computer industry was just getting started (yes: I’m that old), I was hired as Director of Marketing for a company selling hardware and software for auto body shops. Nationwide, they were in last place out of about a dozen competitors. Their major marketing mechanism was exhibiting at trade shows, where they tried to sell business owners a $20,000 system straight from their show booth, with little success.

I replaced that single-step sales pitch with a three-step sales process. I figured out what decision they could reasonably expect a person to make at each step. In the few minutes they had a prospect’s attention at the booth, I changed the sale of a $20,000 to getting the person to sign up for a group presentation at the conference. At the group presentation, the goal was to get them to sign up for an individual consultation at the conference. Only at the individual consultation did we try to sell the $20,000 system.

Each of those three steps had an extremely high success rate. Instead of selling the usual single sale at the conference, they sold over 40. They used this process at every trade show after that, and within two years they were the #1 firm in the industry. A year after that, the company was purchased by a Fortune 500 firm. The only thing that had changed was the addition of a simple process.

– Beverly Sills, American opera singer and opera manager.

In the two decades I’ve spent on regenerating places worldwide, I’ve seen many fail. I’ve seen many move towards an uncertain outcome. And I’ve seen many succeed. But what I’ve never seen is a properly-funded Director of Revitalization whose remit covered all necessary environments: natural, built and socioeconomic. In other words, the whole community or region.

It’s time to get serious about renewing our world. The destruction of our planet has been normalized: we’ve been programmed to expect it as the price of progress. We now need to normalize the recovery of our world. We—and our children—need to expect things to get better. Revitalization could be called “Place Medicine”; restoring wellness to communities, regions, and nations. But where are this medicine’s scientists, doctors and schools?

Many places try to revitalize. Few succeed. Few of the successes last. Resilient prosperity should thus be a primary goal of public management. An ongoing process of fixing the present and the future together is how places revitalize in a resilient manner. Few places aim for resilient prosperity, so devitalization is in the cards for most.

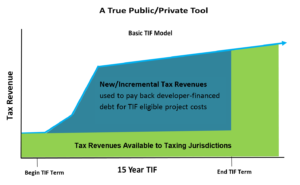

If resilient prosperity is what we want, government should focus on it. And the starting point has to be the revitalization process, along with the myriad “re” activities that comprise it: regeneration, redevelopment, brownfields remediation, historic restoration/reuse, infrastructure renewal, etc. Why? For the same reason that Willy Sutton robbed banks: that’s where the money is.

Of the three components of the adaptive renewal megatrend (which you’ll learn about in Chapter 1)—revitalization, resilience, and adaptive management—understanding the first, revitalization, is the most important. Resilience and adaptive management are of somewhat lesser importance for two reasons: 1) they are both relatively new to the public dialogue, so people are more open to learning about them (whereas most leaders erroneously assume they already understand revitalization); and 2) fewer resources are devoted to resilience and adaptive management in most cities and regions, so there’s not as much to work with.

The downtown area of the Oak Cliff neighborhood in Dallas, Texas is trying to revitalize, despite being severed by a highway. Photo by Michael Barera via Wikimedia.

On the other hand, well over $3 trillion is already spent annually worldwide on urban revitalization and natural resource restoration. Integrating resilience and adaptive management with those existing budgets is thus the quickest way for them to get traction. There’s nothing forced about this 3-way wedding; they reinforce each other quite naturally. Together, they can solve both today’s persistent problems and tomorrow’s unknown—but potentially calamitous—problems.

If you ask a city council to define “revitalization”, how many different answers will you receive? Hint: take the number of council members, and divide by one. Contrary to current practice, revitalization shouldn’t just be a reaction to devitalization: it should be a constant process of breathing new life into a place, regardless of current condition.

In Vietnam, America won most battles, but lost the war. It’s similar in cities: many successful projects, but a failure to revitalize. Part of the problem is ignorance: few communities have anyone who understands the dynamics of revitalization well enough to create a strategy. The other problem is that—even with such a person—they don’t have a Revitalization (or Resilience) Director position in their governance structure. We’ll address this in more detail in the final chapter.

In Chapter 12, you’ll also discover a new, practical way for you to turn this knowledge into a career that helps revitalize your community, or helps regenerate our planet. A vitally-important new type of professional is emerging: the certified Revitalization & Resilience Facilitator. These folks put “RE” after their name, often in addition to certifications from related professions such as planning, architecture, economic development, project management, etc.

We’re capable of tapping deep wellsprings of strength, courage and creativity when family members are in danger. Our economic, ecological, and social future now depends on our extending such concern and compassion to our communities and planet. Our survival—or at least our quality of life—depend on it. Humans and wildlife worldwide are suffering as never before, and both are in greater peril than ever before.

What we destroy, destroys us. Since strategies are our path to success, they become our primary interface with our world, and thus determine in large part how the world responds to us. Thus, what we restore, restores us. What we revitalize, revitalizes us.

- INTRODUCTION - Why your next small renewal project could trigger massive ongoing revitalization.

- PART A - CONTEXT: The challenges of creating resilient prosperity and climate restoration.

It also leads to climate restoration. In my first book, The Restoration Economy, I pointed out that sustainable development is what we should have been doing since the Industrial Revolution started. But we didn’t, so our world is now so depleted, degraded, fragmented and polluted that only restorative development is capable of creating a healthier, wealthier future for all.

That same dynamic has been playing out as regards the global climate crisis. For the past two decades or so, the focus has mostly been on mitigating climate change and adapting to it. The latter is appropriate, since we might well fail to arrest the syndrome before it passes the tipping point (if it hasn’t already) and enters an unstoppable feedback loop.

But saving us from that fate won’t happen as the result of climate mitigation efforts: only climate restoration efforts can do that. Carbon negative, not low-carbon or carbon-neutral. By all means, continue any climate mitigation efforts that are working, but the path forward must be climate restoration.

The good news is that it’s doable, but not just by cleaning-up industry and switching to renewable energy. Those are essential, of course, but there’s a more-oblique path to climate restoration that has vast potential because it’s what everyone wants (even climate crisis deniers): resilient prosperity.

This book is about a path to creating resilient prosperity for communities, regions and nations that simultaneously:

- Grows their economy while boosting environmental health and quality of life;

- Adapts the place to the effects of the climate crisis to make them more resilient; and

- Helps restore the global climate as a side effect, because the regenerative process I describe here—when properly applied—automatically creates carbon-negative economic growth.

In other words, we can revitalize our way to climate restoration.

Every place needs revitalization. City leaders often say “oh, WE don’t need revitalization”, as if it’s something only poor, dirty, post-industrial places do. If I mention a struggling (often ethnic) neighborhood of their city, the reaction is often “well, of course THEY need revitalization.” Any community that thinks it doesn’t need to work on this is probably on its way down. We tend to lose what we take for granted.

They’re also wrong because revitalization isn’t just about the economy. Can any city say that their quality of life and environmental health can’t possibly be any better? Even if a place doesn’t have many assets (like vacant buildings) that need to be repurposed or renewed, their cit almost certainly needs to reconnection. Concentrated wealth and concentrated poverty fragment places, and disguises their overall decline. So, investing in the reconnection and revitalization of distressed neighborhoods is also an investment in social resilience.

Revitalization isn’t defined by current conditions: it’s defined by past conditions, trajectories and trendlines. It doesn’t have to start from a state of distress; just a lower level of whatever you want more of (or a higher level of what you want less of, such as pollution, crime, etc.) Revitalization is defined by the gap between a previous baseline condition—good or bad—and an improved present or future condition.

So revitalization isn’t just for post-industrial economies: it’s for post-bad-planning, post-austerity, post-excessive-economic growth, post-laissez-faire, and post-resting-on-laurels situations as well.

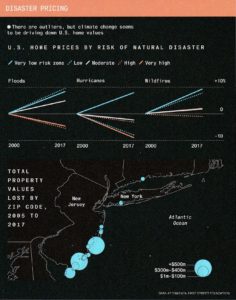

In these days of more and worse disasters fueled by the climate crisis, even places ruled by conservative politicians are realizing they need more resilience.

To avoid repeatedly saying “revitalization and resilience” as if they were separate, unrelated goals, let’s conflate those two universal desires into “resilient prosperity” for the rest of this book to keep things simple.

So, if resilient prosperity is what everyone wants, why do so few enjoy it? Why do so few public leaders know how to create it? That’s what this first section of the book is about.

- Chapter 1 - TRENDS & TERMINOLOGY: Civilization's shift from adaptive conquest to adaptive renewal.

In today’s increasingly broken, dialog-deprived, disaster-fatigued world, we often dive into remedies without understanding the problem, without really talking about the problem, and without even perceiving our level of ignorance. So let’s explore some of the underlying terms, trends and concepts before discussing solutions.

The Adaptive Renewal Megatrend

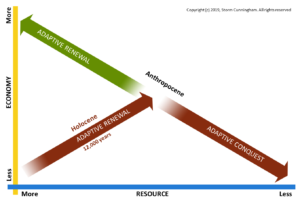

Once upon a time, we humans grew our economies—and accommodated growing populations—by sprawling, and by extracting irreplaceable virgin resources. In other words, we were adapting the planet to our needs, a mode I call adaptive conquest. In most cases, those adaptations were solely for our needs: wildlife be damned.

Many indigenous cultures had ways of limiting their population growth, and used resources in a more sustainable manner. But they usually went the way of wildlife (towards extinction) when the sprawl and extraction machine of adaptive conquest cultures discovered their lands.

That adaptive conquest model has had many unintended consequences—and it has obvious limits on a planet of finite size with a growing population—but it worked fine for about 12,000 years. This was the period that scientists refer to as the Holocene: the epoch during which human activity started to affect the planet.

We’re now in the Anthropocene—which “officially” began in 1950—the epoch during which human activity dominates the planet’s life-supporting processes.

We’re now in the Anthropocene—which “officially” began in 1950—the epoch during which human activity dominates the planet’s life-supporting processes.

How can we survive and even thrive on our tiny planet, despite exploding populations in Africa, Latin America and most of the Muslim world? The only viable alternate mode is to base our economies on restoring our depleted natural resources (and climate), on remediating our vast inventory of contaminated land (and water), and on revitalizing and boosting the capacity of the cities we’ve already created. In other words, we must adapt to our adaptations, a mode I call adaptive renewal.

Economic growth based on adaptive conquest comes in a variety of flavors—capitalism, socialism, communism, etc.—but all are adaptive conquest nonetheless.

– Francis Bacon, British author and statesman.

In the Balearic archipelago of Spain is a paradise called Cabrera Island. It’s part of a sub-archipelago called Archipiélago de Cabrera, which has been a natural reserve since 1991. Here, wildlife flourishes, and human visitors bliss-out on beauty, surrounded by the Mediterranean’s turquoise waters. It wasn’t always so. Between 1973 to 1986, it was a base for the Spanish Armed Forces, although military usage actually goes back to 1916.

Between 1808 and 1814, Isla de Cabrera was a hellhole of suffering for humans and wildlife alike. 9000 of Napoleon’s soldiers were imprisoned there after their defeat in the Peninsular War (when the allied forces of Spain, the United Kingdom, and Portugal repelled Napoleon’s invasion of the Iberian Peninsula). Only 3600 made it out alive, due to starvation, disease, neglect, and abuse.

But the island’s history of adaptive reuse goes even further back. During the 13th and 14th Century, the island was a base of pirate operations, due to its well-concealed harbor. That ended when Cabrera’s castle was built, with its cannons guarding the entrance to the harbor.

Pirate base. Death camp. Armed garrison. Nature reserve. The way humans have constantly adapted the island to their changing needs serves as a microcosmic metaphor for our entire history—and future—on this planet. With the rise of the adaptive renewal megatrend, there’s hope that the entire planet can follow a similar trajectory…similarly ending in paradise. But first we need to know how to manage adaptively—and how to institutionalize the practice—because it’s a very different animal from the old plan-execute-plan-execute model.

– Marc Chagall, Russian-French artist.

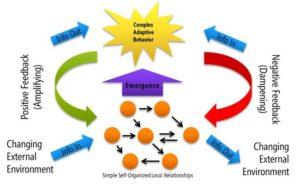

The global adaptive renewal megatrend has arisen from the convergence of three trends, each of which is huge and of vital importance in its own right: regeneration (of natural, built and socioeconomic assets); resilience (physical, economic and social); and adaptive management (which boosts the success of regeneration and resilience efforts by combining learning with action).

Revitalization makes poor places wealthier. It makes wealthy places healthier. It makes healthy, wealthy places healthier, wealthier, and happier. Combining revitalization with resilience makes the good times last. Managing revitalization and resilience efforts in an adaptive manner enables us to take action before we fully understand the problem, and keeps our remedies responsive to new knowledge, challenges and opportunities.

You can recognize the adaptive renewal megatrend at work in places that are constantly repurposing, renewing and reconnecting their natural, built, and socioeconomic environments in an integrated manner, that are monitoring their results and that are improving their methods as they go along.

Resilience efforts are mostly long-term, with few short-term benefits. That makes them a hard sell to both politicians and citizens, and thus difficult to fund. Revitalization, on the other hand, is an easy sell. It’s been the most common political promise for millennia. Combining the two is thus logical. But both revitalization and resilience efforts usually have the same problem: lack of adaptive management.

Adaptive Management

– General Charles de Gaulle, President of France (1958 – 1969)

Under today’s incessant bombardment of change, plans tend to produce great stress for those charged with writing or executing them. Each day, the assumptions on which the plans are based diverge further from reality, yet professional managers are usually required to “stick to the plan”. Adaptive management is a healthy recent trend that allows places and organizations to implement and evolve plans simultaneously. Such a plan is sometimes called a “living document”.

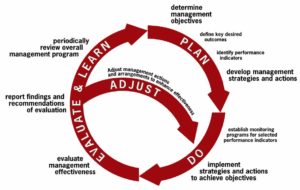

Adaptive management is formally defined as “a structured, iterative process of robust decision making in the face of uncertainty, with an aim to reducing uncertainty over time via system monitoring.” My informal definition is “a flexible management style that learns from—and quickly responds to—reality.”

There are six key steps in adaptive management: 1) assess the problem; 2) design the solution; 3) implement the solution; 4) monitor the results; 5) evaluate the results; 6) adjust the solution. For practical purposes, I normally condense them into three pairs of related steps: 1) assess/design; 2) implement/monitor; 3) evaluate/adjust.

Adaptive management is a global trend in natural resource management that has yet to be widely adopted in urban applications. This is because natural resource managers and restoration ecologists are very aware of the deficiencies in their knowledge. As a result, they wisely developed adaptive management, in which plans are just starting points.

The business world is also catching on. Entrepreneurship professor Steve Blank (UC Berkeley) captured the spirit of adaptive management when he defined a startup as a “temporary organization searching for a repeatable business model.”

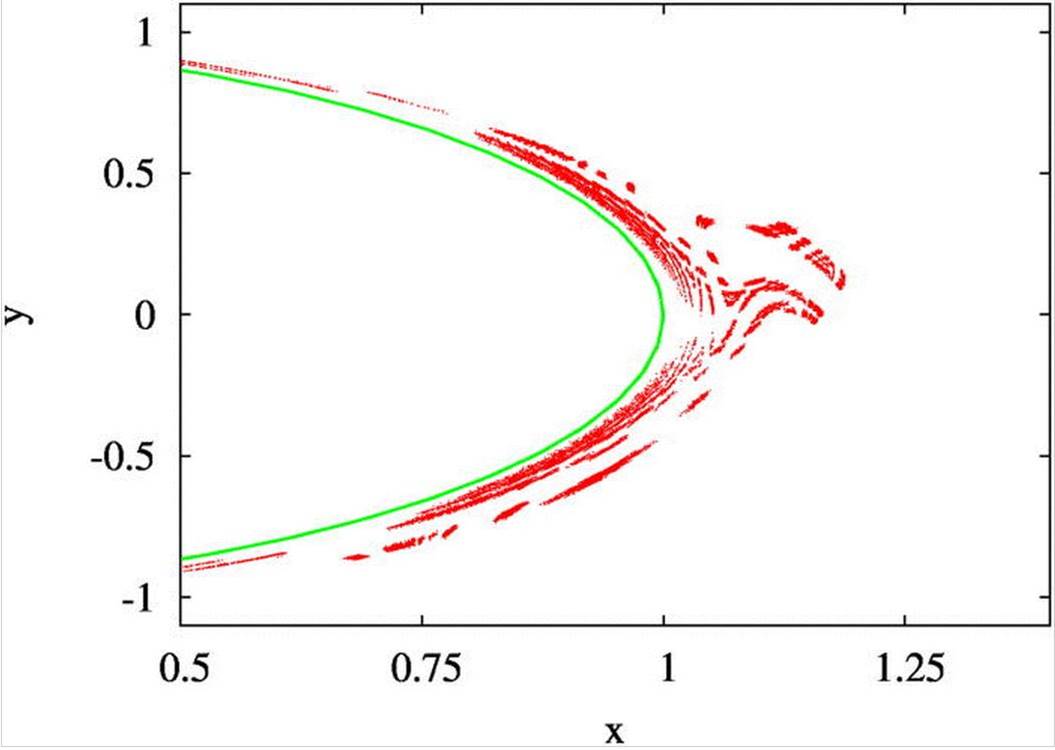

Adaptive management arose primarily from two relatively recent realms of scientific research: 1) restoration ecology (the corresponding practice of which is known as ecological restoration), and 2) complexity science (the study of how complex adaptive systems arise, grow, die and are reborn.

Many insights—both useful and profound—have derived from complexity science, and you use technologies every day that are based on those insights.

Many insights—both useful and profound—have derived from complexity science, and you use technologies every day that are based on those insights.

Here are two of those insights that apply directly to the process of bringing places back to life: (1) Qualitatively new behaviors tend to emerge in dissipative (complex) systems that are out of equilibrium; and (2) Healthy complex systems tend to lie at the border of phase transitions and bifurcation points. The bottom line? Managing change effectively requires a tremendously open and adaptive mindset…one that doesn’t panic when surrounded by uncertainty…one that welcomes and embraces surprise.

I was one of the first 250 members of the Society for Ecological Restoration, and was peripherally involved with the Santa Fe Institute, where I met complexity economist W. Brian Arthur in the late 90’s. I’ve thus been privileged to witness the evolution of both of those new disciplines, and how they have benefited our lives.

Adaptive management arose because the rise of ecological restoration quickly revealed our vast ignorance as to how ecosystems form, how they build and maintain resilience, how they collapse and how they recover.

For centuries, we’ve deluded ourselves into thinking we understood nature, so we simply threw fences around large wildlands, assumed we had conserved them, and developed all around them. In many—maybe most—cases, such “protection” contributed to their devitalization. This was not a learning-intensive process.

Few activities reveal our lack of understanding of natural processes faster than the process of trying to recreate a damaged or destroyed ecosystem. The science of restoration ecology has probably revealed more useful insights into the dynamics of natural systems in the past two decades than we learned in the previous two millennia.

Few activities reveal our lack of understanding of natural processes faster than the process of trying to recreate a damaged or destroyed ecosystem. The science of restoration ecology has probably revealed more useful insights into the dynamics of natural systems in the past two decades than we learned in the previous two millennia.

So, our search for better ways of managing urban revitalization—and the discovery of underlying principles, taxonomies, and frameworks—started with those scientists who bring complex systems back to life for a living: restoration ecologists. Scientists experiment on revitalizing ecosystems in ways that can’t be done on human communities. This can lead to useful insights and metaphors for thinking about cities. One of the most important lessons emerging from the restoration of natural systems is the need for adaptive management.

Urban managers seem to be less aware of their ignorance than ecosystem managers, so comprehensive plans adopted by cities are expected to function unchanged for 5, 10, or even 15 years. But few such plans are ever implemented, and few that are implemented succeed to any significant degree. One thing that’s common to both the failures and the successes is a paucity of monitoring: the process is seldom measured in any rigorous manner, so whatever lessons we learn are usually anecdotal.

Urban leaders seeking socioeconomic revitalization have much to learn from restoration ecology. The results of both their tactics and their strategies are monitored scientifically, and the lessons published in scientific journals such as Restoration Ecology, and in practitioner journals such as Ecological Restoration.

The starting point for this transition to adaptive management in urban environments will likely begin where the city and nature meet.

Here’s a quote from the 2013 Healthy Waterways Strategy report from Melbourne, Queensland, Australia: “Melbourne Water uses adaptive management to ensure that decision making is based on sound and current knowledge. This increases our ability to carry out activities that will result in the greatest gains for waterway health. Adaptive management relies on focused monitoring, investigations and research to build our knowledge of waterways and understand changing environmental conditions, outcomes of management approaches and the effect of external drivers such as climate change. We evaluate these programs to inform our planning and implementation and report outcomes to ensure knowledge is shared.”

New York City’s PlaNYC 2030 plan for adapting to climate change—while accommodating 9 million new residents—is well-designed (the jury is still out on whether it’s well-implemented) because it focuses on three key areas: 1) infrastructure renewal (especially green infrastructure); 2) retrofitting existing buildings; and 3) updating old building codes to current needs. Adapting the natural, built, socioeconomic, and policy/regulatory environments together is where the real magic will be found.

The best plans are not only adaptive, but are based on adapting (repurposing, renewing and/or reconnecting) existing assets. How did Chicago adapt its planning to fix its urban heat island problem, which killed 750 people in 1995? By repurposing roofs. Unlike in many traditional cultures—with their sod, moss or even crop-covered roofs—“modern” roofs are single-purpose: shield occupants from weather. But that design actually changes the local weather. With extremely hot days on the increase (July 2019 was officially the hottest month in recorded history), Chicago has transformed 4 million square feet of roofs into “green roofs”. Besides cooling the city, they:

- reduce flooding from storms;

- help restore Lake Michigan by reducing combined sewer overflow; and

- help restore the climate by absorbing carbon.

Image credit: Worboys, Lockwood, De Lacy: Protected Area Management, Principles & Practice, 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press

Buildings and businesses aren’t the only things that can outlive their form and function. Unchanging building codes, zoning, development incentives, and most other aspects of governance almost inevitably shift from contributing to community progress to retarding it. Keep your policies—not just your plans—adaptive, if you wish to improve your community’s resilience.

But having adaptive policies is one thing. Having the courage to change them when you’re making a lot of money from current bad policies is another. Bad policies can be incredibly destructive, especially those based in the Holocene’s ancient sprawl-based model. When I was doing some work in Belize back in the 80s, a local environmentalist was bemoaning the fact that the only way he could take ownership of the land he loved was by destroying it. The country’s policy then (hopefully no longer) was that any citizen was entitled to land free of charge, provided they clear it first. This “destroy it and it’s yours” policy resulted in widespread devastation of a place whose economy is strongly tourism-based. And most of those tourists come to see nature.

Throughout the 20th century, water engineers seemed to be on a quest to pollute the maximum amount of clean water with any given amount of raw sewage or industrial discharge.

They were driven by a poetic-but-brainless maxim: “the solution to pollution is dilution.” But diluting 1 gallon of sewage with 100 gallons of clean water simply yields 101 gallons of polluted water. Diluting 1 gallon of sewage with 100,000 gallons of clean water yields 100,001 gallons of polluted water.

Combined sewer and stormwater systems made sense a century ago, when urban populations were relatively small, sewage treatment technologies were not in wide use, and cities still had significant amounts of permeable surfaces to absorb rainwater.

Flushing sewers with stormwater could be forgiven then, but what shouldn’t be forgiven is how long it took communities to stop specifying them, and how long it took civil engineers to stop recommending them…decades after combined sewer overflows (CSO) were recognized as a crisis.

The need for adaptive management isn’t the only lesson in managing urban areas that we can derive from the science of restoring ecosystems, of course. Three examples of other potential crossover lessons:

- Restoration ecologists speak of “reparative restoration” (fixing damage, such as by reintroducing native species) versus “replacement restoration” (providing functional equivalents, such as hunters replacing wolves as top predators).

- Lesson: Cities suffering industrial flight to lower-wage countries could choose between recruiting functionally equivalent employers versus restoring jobs by “repurposing” citizens via education, training, and entrepreneurial support.

- Restoration ecologists can’t restore nature 100%, so they aim for resilience. They use “foundational” species—such as corals, seagrasses, and oysters—that form the structural basis of ecosystems and contribute most to community stability. Nature then takes over, repairing itself and diversifying without further intervention.

- Lesson: With limited funding, public leaders must focus on reaching the revitalization tipping point, where the free market takes over. This often involves renewing foundational assets; infrastructure, water, heritage, public services, etc.

- Here’s a quote from the paper “The Rapid Riparian Revegetation (R3) Approach” in Ecological Restoration (June 2014): “With hundreds of thousands of kilometers of riparian corridors in need of restoration, and limited public funds for implementation, practitioners need to identify strategies that lower the unit cost and accelerate the pace of reestablishment of native riparian forests in sustainable ways. The R3 approach is grounded in ecological principles and geared towards producing outcomes consistent with restoration programming and the human desire to see “progress” for the investments made.”

- Lesson: Replace “riparian corridors” with “cities”, have R3 stand for “rapid resilient renewal”, and this passage describes good urban strategies.

The constant arrival and territorial expansion of invasive species is just one of myriad factors creating a need for adaptive management of landscapes. In the U.S. alone, there are over 5000 invasive plant and animal species. A very conservative estimate by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service puts their annual national economic damage at about $120 billion.

Those charged with managing the problem have to juggle removing well-established invasive species, reducing the introduction of new invasive species, and reestablishing native species…all while the climate is changing and human activities are altering the air, soil and water. Creating an effective, static long-term plan for such a mission under such circumstances is quite literally impossible. The only static situations are those devoid of life. Strategies and tactics must adapt not only to the changing situation, but to the changes they themselves cause, resulting in a constant—and often accelerating—loop of cause and effect, feedback and evolution.

it’s about learning to dance in the rain.”

– Vivian Greene

This ignorance of complex adaptive systems dynamics is rife among managers of systems other than nature, such as human societies and economies. As a result, adaptive management is appearing everywhere, though often not by that name. Business people, for instance, have probably encountered the Minimum Viable Product strategy used by many technology start-ups. That’s an example of adaptive management.

The “adaptive” in adaptive renewal might best be defined in terms of flow. Want a specific example of using adaptive management to revitalize a downtown? Look at parking policies and traffic flow.

Some say free or cheap parking causes traffic jams and undermines efforts to improve public transit. Others say traffic jams are a good problem to have: the goal is more shoppers, so the more free parking, the better. Still others say expensive parking is best: it encourages pedestrian-friendly, transit-oriented development, and the increased revenue funds downtown improvements. Who’s right? All of them are.

Downtowns evolve and devolve like all living systems, so parking policies must adapt to current problems, needs and goals. If a downtown has a dearth of retail, then scaring people away with expensive, strongly-enforced parking isn’t a good idea. It only takes one downtown parking ticket to convince a shopper that the sprawl mall is the better place to go. In that case, a switch to free parking might stimulate more visitors. This will encourage more retailers, which will stimulate more visitors, and so on in a positive feedback loop of revitalization.

But if that loop continues long enough, it will eventually result in traffic jams. That will make the downtown noisy, polluted, and dangerous for pedestrians, and they’ll start coming less often. Parking fees can then be reintroduced, starting with cheap parking. If that doesn’t bring traffic down to levels that restore the quality of downtown life, they can be hiked again, until the right balance is achieved.

But then someone is bound to say “Ah: we’ve found the right balance. Let’s engrave this parking price in stone.” Now they’re heading for trouble again, because, again, cities are complex, living systems, and healthy systems never stay the same.

Parking policies are deceptively simple, but they are just one of myriad factors affecting the health and survival of your community that can be managed via policies. So, parking is a good place to start your journey into adaptive public management. Taking an adaptive approach to policymaking is a core element of resilience planning, but it’s rarely practiced. I’ve seen many recent resilience plans for cities: few even mention adaptive management, much less were based on it.

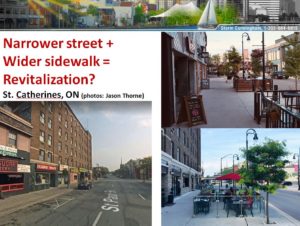

When Manhattan’s Times Square was pedestrianized, cars were completely banned. The rate of visitors quadrupled (delighting the merchants) and the crime rate dropped by half. So to many cars degrade a city center, as can a paucity of cars. The “right” number can revitalize it, and that number might be zero.

What revitalizes a dying place might devitalize a vibrant place. And what revitalizes a place now can kill the same place later. Such complexities are anathema to most public leaders, who like simple, easy “solutions.” Adaptive management is a lot easier to write about than it is to practice, but fear not: technology is coming to the rescue.

We now have systems enabling real-time adaptability, as with demand-price parking meters, similar to Uber’s surge pricing. So, revisions to parking policies might not be needed as frequently as before, as algorithms take over. Maybe we will one day have an Internet of Renewal (IoR) to go along with our Internet of Things (IoT): verb-based, rather than noun-based software.

Here’s a recent example of this adaptive traffic flow dynamic at work. In April 2018, Buffalo, New York was on the verge of wasting a hoped-for TIGER Grant. This was a vestige of the late-and-lamented Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery program that helped revitalize many cities during the Obama administration, and which has been reincarnated by the Trump administration in a lobotomized form (it ignores most of what we’ve learned about cities in the past 30 years) rebranded as BUILD Grants.

Over 30 years ago, Buffalo city leaders were ahead of their time in banning cars from their Main Street. This greatly improved the quality of life downtown, but the desired economic revitalization never manifested.

The problem is that they never followed-through on the logical next step after eliminating the traffic problem: taking advantage of that increased quality of life to add what the downtown (and its businesses) desperately needed: more residents. One would think that the relationship of housing to residents to customers would be fairly easy to perceive. Not so at that time in Buffalo, apparently.

How did they plan to revitalize Main Street? By spending that precious TIGER Grant on restoring automobile traffic! Cars don’t buy goods. Pedestrians do. This is the kind of wasteful, self-destructive decision that cities make when they don’t think strategically. A good strategy affects the underlying cause to create the desired effect.

Adaptive management is the key to dealing with evolving challenges and evolving tools (like surge pricing and smart meters) in an evolving environment that we are changing as a result of our adaptive management…and doing so when we don’t fully understand the dynamics of the system we wish to revitalize.

Pittsburgh’s Mayor Bill Peduto is one public leader who “gets it”: he’s taking an adaptive management approach to the city’s multi-decade, multi-river restoration challenge. Other city, county, state, national and multinational leaders are now doing likewise, as we’ll see in a moment.

With all this constant, self-referential adaptation, we need to be especially careful that we don’t lose sight of our goal. Any changes made to strategies, plans, and projects should reference the vision, to prevent “mission drift”. As Steven Covey says, “The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.” That’s the importance of basing your resilient prosperity efforts on a shared vision, as we’ll describe later.

Oscar Wilde described the importance of having an inspiring vision when he said “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” The function of a clear vision is to keep an iterative (adaptive) strategy or iterative plan from iterating itself into a hole.

– Mike Tyson

There are several ways of interpreting Mike Tyson’s well-known above quote. It might mean that most people panic in the face of adversity, and lose track of their purpose. It might mean that having a plan is useless. Or, it might mean that having a fixed plan is useless: when it’s reality that’s punching us in the mouth, the plan must be adapted to reality. But in the rapidly-changing circumstances of a boxing match, it wouldn’t a plan that’s being adapted: it would be the strategy. (Referees frown on fighters consulting documents while they’re in the ring.)

Large institutions seldom announce that they are switching from a “follow the plan at all costs” approach to an adaptive management approach.

This is partly because once it’s understood, it makes their previous leadership look less than brilliant, and some of those previous leaders might now be on the board. But it’s mainly because the process of adopting an adaptive approach should itself be adaptive. (Say that three times rapidly!)

For instance, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is the federal agency responsible for administering civilian (i.e. non-defense-related) foreign aid. USAID’s annual budget is about $36 billion.

USAID has recently been embedding adaptive management into its funding mechanisms, but you’d hardly know it if you weren’t directly involved in the process. They refer to it as the CLA Framework (Collaborating, Learning, Adapting).

In their new Program Cycle Operational Policy, they state that one of the three key requirements of funding applications from their international partners is “Learning from performance monitoring, evaluations, and other relevant sources of information to make course corrections as needed and inform future programming.”

For those involved in modern disaster-response and/or climate crisis adaptation initiatives, no such cultural change is needed: any true professional working in those areas knows that adaptive management is not optional.

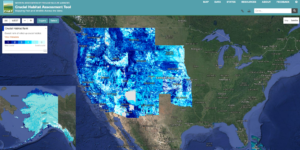

A recent example of this can be found in the draft Adaptive Management Plan, published in October of 2016 by Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

A recent example of this can be found in the draft Adaptive Management Plan, published in October of 2016 by Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

The switch to adaptive management need not be disruptive. After all, all one is really doing is injecting common sense into the previously rigid, blind-faith-in-the-plan culture. Or, as Divyesh Mistry of the Toronto Transit Commission says: “Cities change. Get over it.”

Due to the rapid rise in vacant commercial properties—malls, big box stores, office buildings, etc.—some architects are finally starting to think about designing buildings in a way that facilitates eventual adaptive reuse.

The architecture firm Gensler invented the term “hackable” buildings back in 2014 to capture the idea. They feel we should be constructing—and renovating—in a way that accommodates the desired immediate use, but that responds to changing market demands or preferences by making it easy for the structure to be reworked for a productive new life. It’s basically a proactive approach to the concepts Stewart Brand laid out in the classic book, “How Buildings Learn.”

The architecture firm Gensler invented the term “hackable” buildings back in 2014 to capture the idea. They feel we should be constructing—and renovating—in a way that accommodates the desired immediate use, but that responds to changing market demands or preferences by making it easy for the structure to be reworked for a productive new life. It’s basically a proactive approach to the concepts Stewart Brand laid out in the classic book, “How Buildings Learn.”

In today’s climate of constant crisis and heightened uncertainty, planning for success means assuming the plan will probably fail, but not the project or program. Projects, plans, and programs for improving our built, natural, socioeconomic, and geopolitical environments must adapt not just to rapid change, but to an accelerating rate of change in each of these intrinsically-connected arenas.

Such conditions are highly corrosive to 5-year plans, which now decompose and putrefy at an accelerated rate. Longer-term plans are best suited to fundraising pitches, political posturing, and other fiction-rich endeavors. That said, the process of planning is often of great value, even when the relevance of the resulting plan is decaying even while it’s still being written. An evolutionary ethos is the key to success in such an environment.

– Bruce Lee (on creating a new style of martial art).

The only preservative we can add to our rust-prone plans is adaptability. Once implementation begins, we must be ready to defenestrate our highly-perishable plans at a moment’s notice, lest they become toxic to our future. These days, only our shared visions of our desired future should be long-term, not the strategies, policies or plans we devise for achieving them. Adaptive management provides the flexibility (and reflects the humility) needed to deal with today’s social, economic, political, and environmental precariousness.

While some manifestations of the adaptive renewal megatrend are well-established, many others are more recent or are still emerging. The latter include adaptive strategies related to climate change, sea level rise, and natural disasters, such as for cities, agriculture, and natural resources (including the creation of novel ecosystems).

Experts sometimes refer to “passive” vs. “active” adaptive management. Passive adaptive management is normal planning plus the monitoring and evaluation of results. Common sense, in other words. The passive form was invented to allow traditional managers to say they use adaptive management when they don’t have the courage for it. The active form is what we’ve been discussing here.

Surprise!

As mentioned earlier, one characteristic that defines all living systems is the capacity to surprise. Adaptive management could thus be called “surprise management”. It’s the polar opposite of the engineering-based approach that dominates public management today.

Elwha Dam in 2005. Built in 1913, demolished in 2012. The Elwha River and its salmon runs have spectacularly come back to life. Photo: Larry Ward, Lower Elwha Fisheries Office.

In addition to maximizing efficiency, the primary purpose of an engineer is to eliminate surprises. This is wonderful skill when dealing with structures: no one likes driving over a bridge that behaves in an unpredictable manner. But it’s a disaster when dealing with ecosystems or cities. Removing surprises from a living system is synonymous with killing it.

But even their efficiency goal can be problematic. Again: it’s desirable for mechanical and structural engineering work, but is often inappropriate when applied by civil engineers working on complex systems. Nature does many things that are inefficient in the microcosm, but highly efficient in the macrocosm. Plants create thousands of seeds—and fish lay thousands of eggs—since maybe 1/10th of 1% will reach reproductive age. The rest become food for other species. Forest fires are another example of (apparent) waste, and we’ve now seen the vast damage done to our ecosystems (and towns) when we try to engineer fires out of existence.

These are two of the major reasons the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—in controlling the life out of our estuaries and waterways—has done more economic damage to America than all foreign armies combined. It’s also why China might eventually be headed towards another national meltdown: they have far more engineers in local and national government than any other country.

Manhattan’s magnificent High Line Park (which we’ll return to later) is emblematic of the adaptive renewal megatrend. It created jobs, boosted real estate values, and increased quality of life. It revitalized, in other words. The High Line was initially a bottom-up flow, a resident-led effort that led to a top-down flow of support by the city. It accomplished all of this through reuse of existing assets (an elevated railroad track), which reconnected neighborhoods and reestablished flows. These are the trends and models you’ll see throughout this book.

Single-use places are a form of disconnection and isolation, whether urban or agricultural. Civil engineering has traditionally been oriented toward isolating functions, separating asset types and preventing flows. So, it’s not just that adaptive conquest must shift to adaptive renewal: the nature of our adaptations must shift from our traditional mode of fragmenting systems, blocking flows and eradicating surprises to a mode of reconnecting systems, restoring flows and encouraging surprises.

Terminology and Concepts

What we’re doing is protecting against future damage, but there’s not a new positive cash flow.

You’re not creating new value. You’re protecting against the loss of existing value.”

– David Levy, management professor at the University of Massachusetts – Boston.

Revitalization is the process of regaining lost vitality.

Resilience is the process of retaining vitality.

Resilient prosperity is the process of regaining and retaining vitality.

Terminology is important, and becomes even more important when huge sums of money—and the future of communities—are involved. In the 50s and 60s, the U.S. federal government offered cities hundreds of millions of dollars to revitalize any area they labeled “blighted.” White politicians and urban planners usually decided that the word meant any place with large numbers of darker-skinned, lower-income people and/or immigrants. Hundreds of vibrant neighborhoods were demolished as a result, all in the name of “urban renewal.” A more-rigorous definition of blight embedded in policy might have prevented a lot of unnecessary suffering.

While most articles about the horrors of urban renewal focus (rightly) on the human cost, it should be noted that vast numbers of manufacturers and retail businesses fled the downtowns for the suburbs while all of the physical devastation was taking place. This was an example of destructive federal policymaking: the catalytic funding initially came from the Housing Act of 1949, and was accelerated by the National Interstate Defense and Highways Act of 1956. It was called “urban renewal”, but it was just demolition and new infrastructure. A more-rigorous definition of revitalization might have prevented a lot of unnecessary devitalization.

My current working definition of revitalization: “Revitalization is a cycle of rising optimism, equitable prosperity, quality of life, and environmental health—usually triggered by renewing, reconnecting, and/ or repurposing distressed natural, built, socioeconomic, and human assets—and often preceded by a cycle of devitalization.”

The 2008 movie, Slum Dog Millionaire was praised outside India, but largely reviled within India. Why? Because it perpetuated the faulty perceptions of slum life that help Westerners feel superior. It ignored the positive aspects of slum communities, which can often make American suburbs look dysfunctional—even sociopathic—by comparison. These days, many socially-rich slums are being bulldozed In India, to be replaced with the isolated, anonymous life of apartment and condo towers.

In his December 19, 2014 article in Global Site Plans, “Why Some Mumbai, India Slum Dwellers Prefer Slums to Condos”, writer Adwitya Das Gupta quoted his slum-dwelling maid as “If I am late from work, my neighbours bring my children dinner and make sure they are taken care of without me needing to ask… I have friends there and people I can rely on. Why would I want to move? I think the communities we have there are much stronger than you would even have here.”

Maybe we need to redefine “slum”. Those examples are just a tiny sampling of the suffering that can arise from imprecise terminology. Sometimes, a perfectly good word takes on a negative meaning as a result of bad practices. In Milton Keynes, England several public housing projects are being demolished and replaced with better housing. But it’s apparently being done in a way that results in unnecessarily-high levels of displacement and social trauma.

A February 28, 2019 article in the Milton Keynes Citizen reported that Former Milton Keynes Council leader Kevin Wilson said “I want the word regeneration replaced with something more community-inclusive. The word ‘regeneration’ has become synonymous with the word ‘demolition’. The moment that you raise the spectre of ‘regeneration’, residents think that you are hiding something. The word itself has become toxic.”

In February of 2019, the Colorado Springs City Council was asked to declare 40 acres of virgin greenfields in the foothills to be an “urban renewal” zone. Some city leaders wanted to boost their tourism revenue by letting the U.S. Air Force Academy build a new 57-acre visitors’ center in this sprawl area.

The visitors center may or may not be a good idea, but calling it “urban renewal” is most definitely a bad idea. Doing so will undermine the city’s credibility in any future attempts to attract state or federal revitalization funding. This behavior certainly isn’t limited to Colorado: any time national governments create a pot of money with a given label, local politicians will call their project whatever’s necessary to get their hands on it.

That abuse of terminology in the scramble for money isn’t always totally misguided. In Michigan, for instance, any vacant property (usually residential) that’s accepted into a local land bank’s inventory is automatically designated a brownfield, whether or not there’s any suspected or actual contamination. This gives the land bank access to state brownfields funding.

That’s terminological misuse in a good cause, but it could undermine “real” brownfields reuse efforts. On the other hand, every plot of land on the planet is contaminated by something—old lead-based paint, oil leaks from vehicles, brake pad dust, etc.—so it’s a relative term. Most homes and lawns in the U.S. could be considered brownfields, given the heavy applications of toxins to kill weeds, mosquitoes, termites, fleas, rats, etc.

And so it is with resilience, where terminological fuzziness abounds. Part of the problem is that people often say they seek community resilience without specifying the type of resilience: social, natural disaster, climate, economic, etc. Or, they aren’t aware that all of those types of resilience must be addressed to create real community resilience.

As a community revitalizes, it increases its capacity of reaping the resilience dividend.”

– Dr. Judith Rodin, former President of The Rockefeller Foundation (2014)

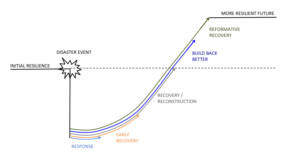

If you’re new to the study of resilience, let me explain the “bouncing forward” reference in Dr. Rodin’s above quote about revitalization and resilience. Traditionally, cities hit by catastrophe (whether sudden and natural, or gradual and socioeconomic) have rather mindlessly gone about rebuilding in a way that merely reconstructed what had been lost. Their goal was to “bounce back.”

If resilience is your goal, you want to “bounce forward”…rebuilding better than you were before, in a way that makes you less vulnerable to future disasters. One might call this “preemptive planning”. Leadership of ANY kind can be actually defined as “acting before one has to,” which fits a resilience agenda perfectly.

I described this concept in my 2002 book, The Restoration Economy, showing how Lisbon, Portugal rebuilt the entire city on higher ground after a massive earthquake and tsunami in 1755.

They were also smart enough to take advantage of the opportunity to correct a number of urban planning mistakes (actually, lack of planning). That redesign was led by the Marquês de Pombal, who is sometimes called the world’s first urban planner. He was probably Robert Moses’ inspiration, as his style of planning has been called “despotic.” Nonetheless, the present-day result is one of the world’s most beautiful cities.

“Bouncing forward” is, in fact, a pretty good example of a strategy: it’s succinct, memorable, an effective guide in decision-making, and reliably successful when well-implemented in the right place at the right time. Unfortunately, government bureaucracies are often stuck in “bounce-back” mode, as FEMA has often demonstrated. Even worse are maladaptive recovery efforts that actually compound problems (usually due to short-term, palliative thinking and/or budget constraints from tax cuts).

– Chelsea Clinton, Vice Chair of the Clinton Foundation

Again: resilience is revitalization plus adaptability. Revitalization makes poor (or damaged) places wealthier, and wealthy places healthier. It makes healthy, wealthy places healthier, wealthier, and happier. Adaptability helps make the good times last. Resilient prosperity, in other words.

We should keep in mind that health and wealth (both in their holistic senses) are emergent qualities of doing the right things in the right way for the right amount of time. So, they should not be goals in themselves. Their nature is too ephemeral, and their emergence is too unpredictable to serve as deliverables. As Eleanor Roosevelt wisely said of another ephemeral goal: “Happiness is not a goal…it’s a by-product.”

Most folks define resilience along the lines of “the ability to bounce back from adversity or trauma, or adjust to change”. Traditionally applied primarily to materials and individuals, it has now become a goal of institutions and communities (as well as restored ecosystems). [Note: I use “resilience” in this book, rather than “resiliency.” Their meanings are identical, and both are real words. But “resiliency” is mostly used in casual American conversation. This guide uses the shorter, more elegant form preferred by scientists and educators, and by most English-speakers worldwide.]

A systems-oriented definition of resilience is: “the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and re-organize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks.”

A systems-oriented definition of resilience is: “the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and re-organize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks.”

In their 2012 book Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back, authors Zolli and Healy offer an institutionally-oriented definition: “the capacity of a system, enterprise, or a person to maintain its core purpose and integrity in the face of dramatically changed circumstances.”

Resilient solutions are normally 1) redundant (to endure loss or damage); 2) flexible/scalable (to endure growth, contraction, and change); and 3) integrative/strategic (to endure time and heal fragmentation).

The desire for revitalization can be triggered by a long, slow decline, a sudden disaster, or simply dissatisfaction with the current quality of life. The desire for resilience is often triggered by recent or impending disaster: a fishery on the edge of collapse, a fragile economy, climate-related agricultural challenges, etc. So, revitalization is motivated by present-day pain, whereas resilience is motivated by a desire to avoid future pain. The two goals have obvious overlaps.

This book is not about resilience in the traditional sense. There are many excellent books on that subject. One of the more recent is The Resilience Dividend, by the Rockefeller Foundation’s former CEO, Dr. Judith Rodin, published in November of 2014. Her 384-page work on resilience was especially insightful because it included a chapter on revitalization.

This book is not about resilience in the traditional sense. There are many excellent books on that subject. One of the more recent is The Resilience Dividend, by the Rockefeller Foundation’s former CEO, Dr. Judith Rodin, published in November of 2014. Her 384-page work on resilience was especially insightful because it included a chapter on revitalization.

This book, RECONOMICS, has the opposite emphasis: it focuses more heavily on revitalization, and its role in resilience. That’s because resilience is the poorly-funded newcomer, whereas revitalization, regeneration, and redevelopment agencies and budgets have been around for decades, if not centuries. Refocusing these established community and regional assets on resilient prosperity is thus the low-hanging fruit. An obvious and frequent connection between resilience and regeneration is in post-disaster situations.

This book thus comes at resilience from an oblique angle. Rather than focusing on traditional resilience strategies, it shows how the parallel trends/activities of community revitalization and natural resource restoration are ideal paths to a resilience effort. This is as opposed to launching yet another silo, this one called “resilience.”