This Guest Article for REVITALIZATION is by Dr. Sandra Piesik.

We are running out of time. The International Labour Organisation in its World Employment Social Outlook 2018 Greening with Jobs provides these staggering statistics:

“Some 1.2 billion jobs, or 40 per cent of total world employment, most of which are in Africa and Asia and the Pacific, depend directly on ecosystem services, and jobs everywhere are dependent on a stable environment. Every year, on average, natural disasters caused or exacerbated by humanity result in the loss of 23 million working-life years, or the equivalent of 0.8 per cent of a year’s work. Even in a scenario of effective climate change mitigation, temperature increases resulting from climate change will lead to the loss of the equivalent of 72 million full-time jobs by 2030 due to heat stress. Developing countries and the most vulnerable population groups are most exposed to these impacts.“1

River-flooded homes in the United States of America. Across the globe, flooding has killed millions of people in the past hundred years – more than any other type of weather phenomenon. River floodplains and coastal regions are the areas most at risk, though floods result from a range of different processes.

Humanity urgently needs productive landscapes and ecosystems to avoid the self-extinction of the kind seen on Easter Island, but regenerating degraded land and ecosystems with reduced biodiversity takes time. It takes longer to restore degraded land than it does to destroy it.

According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in Those Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Desertification, Particularly in Africa, 169 countries have declared that they are affected by desertification. More than 1.5 billion people directly depend on land that is slowly being degraded.2

One of the biggest challenges of our time is the acceptance across all spectra of society that we need change and communicating this message to all to the ordinary citizens. Desertification, floods, amplified hurricanes and cyclones and melting ice in Siberia for the first time in 40,000 years are profound and irreversible changes to our landscapes and unless people live in the affected areas we can be indifferent, because it does not affect someone in a personal or individual way.

Numerous UN organisations and political leaders are calling for collective action across all spectra of society, and it is in the hands of all of us: governments, both national and local, nongovernmental organisations, civil society, those in higher education, indigenous people and every citizen to take action – because it will only be possible to reverse the current path of self–destruction into which we are heading by collective global action. This requires a change of mindset.

We have no control. Virtual habitat.

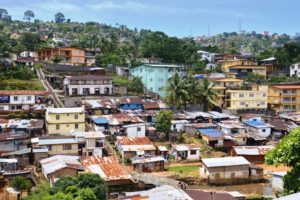

Uncontrolled urban growth in Freetown, Sierra Loene, West Africa, has created slums, many of which are built from imported materials and systems that do not respond well to the conditions of the local environment.

It is fair to say that we no longer have control over “Mother Nature” but some control to reverse the changing planetary ecosystems.

However, it is worth acknowledging that we also no longer have control over technological developments; in March 2019 Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, asked governments for help in regulating Facebook and the internet as Facebook is no longer able to provide adequate protection for its users, and this is only the tip of the iceberg.

According to Loril Lewis, in one internet minute (that is just 60 seconds) in 2019 – over 266 million users are engaging with activities in virtual space on Google, Facebook, YouTube, etc.3 It means that we are meeting in a virtual space of artificial and intangible landscapes and ecosystems which we have created, wholly detached from nature and tangible landscapes and tangible human relationships.

We have no control over the development of technology, and we have no control over the virtual space that more and more people have decided to inhabit, detached from tangible landscapes.

Natural habitat.

Village houses set in the landscape of Madagascar’s central highlands represent the regions’ more humble built expression.

Whilst the logical conclusion suggests that we are heading into an apocalyptic disaster, there is a part of us that says that with all the data available we can and must take action.

Despite phenomenal advancements in collective data and the increasingly important sophistication of spreadsheets, the evidence is that the data has not led to increased action on climate change.

Deep down, the majority of men and women have a desire to connect with nature, to be with nature and to experience its healing power and beauty. This is where we can regenerate and where we can feel at our best.

Our evolutionary development is a tiny part of the over 4 billion years of Planet Earth’s existence; we came into the picture over 250,000 years ago. The development of agriculture in 12,000–10,000 BC meant that people became more settled, and somehow we manged to create cities and habitats in co-existence with a natural habitat.

“HABITAT: Vernacular Architecture for a Changing Planet”4 offers the first contemporary global review of vernacular architecture carried out in the past twenty years. Organised according to the five major climate zones: tropical, desert, continental, temperate and polar regions; and covering more than one hundred countries worldwide, the encyclopaedia reveals how peoples and cultures have adapted to their environment to make the best use of indigenous materials and construction techniques, and stresses the importance of preserving disappearing craftsmanship and local knowledge before it is too late.

The overarching conclusion of HABITAT is the interconnectedness of the planet’s five major ecosystems with the built environment. Civilisations maintained this interconnectedness between natural habitat and landscapes and built habitat until the First and the Second Industrial Revolutions of 1760 and 1820. Gradual but persistent detachment from our presumed independency from nature commenced during this period. Climate change scientists take this time frame as a benchmark for measuring human impact on the environment of the “pre-industrial level”.

The pre-industrial period of our relationship with nature is important. It demonstrates a way of living in harmony with nature, and more importantly technologies for the built environment, developed through evolution and tested by time. This was “The Cornerstone” of our habitat and coexistence with the natural habitat.

Conceptual problem of progress.

Technology School of Guelmim, Morocco. The starting point for the project was to provide a strong architectural form that was contemporary but was also inspired by the context in which it occurs.

The speed of developmental changes, the discovery of oil in the Gulf Region in 1970s, transport and communication, interconnectedness leading to globalisation meant that the conceptual framework of progress changed somehow. Our distorted conceptual framework of progress is detached from our relationship with the natural world.

Indigenous people with the same access to technology want upgrades to their houses that traditional building materials are not always able to offer. Modernity is manifested through concrete blocks, corrugated roofs, plastic pollution and excessive use of glass. Globalised westernisation, created in the context of temperate and continental climates, invaded other climate zones and it is a two–way process.

On the one hand architects and town planners continue to design imitations of the western world in other climate zones, and on the other hand, indigenous people themselves do not really want to go back to the past or live in the houses of their grandparents. Although we know that traditional solutions were good for the environment, many people no longer want to live in traditional houses.

Heritage-driven regeneration is almost always successful, but it is not a mainstream approach to development, and with the magnitude of the climate change challenges facing us we need more to be done, and to be done more quickly. We need a paradigm shift and we need a change of paradigm at the global scale.

Adaptive resilience.

The Stone Rejected by the Builders Has Become the Cornerstone.5 It is in our past relationship with nature that we can rebuild and restore the new paradigm of coexistence with nature that is needed. It is the “rejected stone”.

Adaptive landscapes, adaptation and restoration of ecosystems, nature-based solutions, land degradation neutrality, bio-economy, circular economy and all the other trends that direct us into a new understanding of our equilibrium of living with nature matter.

The key issue is an attempt to try to bring about small steps in local community and local government collaboration, to do small incremental changes and actions on the ground. We have passed the stage of statistics and the rationale of why we need to do this – it is time for action on the ground across the entire spectrum of stakeholders involved in cities, rural areas and forests regeneration.

In April 2019, the Green Climate Fund launched its first working paper on Adaptation: Accelerating action towards a climate resilient future.6 According to the Oxford English Dictionary it defines resilience as “the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties”.7 Here the focus is on recovery or bouncing back from a shock or a disaster.

The UN’s International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) defines resilience as “the ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate to and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions”.8 Resilience does not necessarily involve adaptation if it means simply returning to the status quo.

However, resilience is closely related to the vulnerability of people or communities: the greater their vulnerability to the impact of climate change, the lower their resilience, and vice versa. Here is where an overlap with adaptation exists. For example, when disaster risk reduction efforts work to reduce people’s vulnerability and build their resilience through integrated flood management, improving water supply systems or strengthening agricultural value chains, that is adaptation.

By contrast, if people simply rebuild their houses and businesses after a hurricane or a flood in order to live as they did before the disaster, they are demonstrating their resilience, but this cannot be termed adaptation. Post-disaster recovery efforts are adaptive only if they include a transformative shift towards more sustainable systems – a concept of transformative resilience.9

The planet and humanity need a transformative resilience of minds, natural landscapes and the built environment in a collective effort to accept the status quo. The stone of the past, rejected by modernity holds some vital clues on how to adapt to our sustainable future without leaving no one behind.10

All images courtesy: “HABITAT: Vernacular Architecture for a Changing Planet” edited by Sandra Piesik Published in London by Thames & Hudson (2017), in the USA by Abrams, France by Flammarion, Germany by Edition DETAIL and Spain by Blume.

About the Author:

Dr. Sandra Piesik is an award-winning architect, author and researcher specialising in adaptation of traditional knowledge, urban – rural dynamics and the implementation of global sustainable legislation.

Dr. Sandra Piesik is an award-winning architect, author and researcher specialising in adaptation of traditional knowledge, urban – rural dynamics and the implementation of global sustainable legislation.

She is the founder of 3 ideas Ltd, a Policy Support Consultant on Rural – Urban Dynamics to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), a Visiting Professor at the UCL Global Institute for Prosperity, initiator of several RD&D groups and consortia including HABITAT Coalition.

She is a stakeholder and network member of several organisations including UN-HABITAT Urban – Rural Linkages; the Nairobi Work Programme (NWP), the Resilience Frontiers, the Paris Committee on Capacity Building (PCCB) and Climate and Technology Centre & Network (CTCN) of UNFCCC. Her published work includes Arish: Palm-Leaf Architecture (Thames & Hudson 2012) and she is the general editor of the encyclopaedia, HABITAT: Vernacular Architecture for a Changing Planet (Thames & Hudson, Abrams Books, Flammarion, Editions Detail and Blume 2017).

Website: 3ideasme.com

Twitter: @SandraPiesik

- The International Labour Organisation on its World Employment Social Outlook 2018 Greening with Jobs, 0.5

- https://www.unccd.int/actions/united-nations-decade-deserts-2010-2020-and-fight-against-desertification

- @LoriLewis

- “HABITAT: Vernacular Architecture for a Changing Planet”, edited by Sandra Piesik, published by Thames & Hudson 2017

- Psalm 188:22, The Jerusalem Bible, Popular Edition, General Editor, Alexander Jones, Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd, 1974

- Adaptation: Accelerating action towards a climate resilient future, Green Climate Found working paper No 1, April 2019

- Oxford English Dictionary, “Resilience”, Oxford Dictionary I English accessed March 23, 2019

- UNISDR, “2009 UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction,’ ISDR, 2009, accessed March 23, 2019

- Adaptation: Accelerating action towards a climate resilient future, Green Climate Found working paper No 1, April 2019

- “Leaving no one behind” Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 2015