Back around 2004 or 2005, I (Storm) was taken on a tour of the Stapleton redevelopment in Denver, Colorado by Melissa Knott, who was then Director of Sustainability for Forest City, the prime redeveloper of this wonderful project.

Melissa is the daughter of John L. Knott, Jr., the visionary real estate redeveloper. At the time, he was bringing me down to South Carolina on a regular basis to do workshops for both his team and the local community. John’s spectacular Noisette Project revitalization plan for North Charleston was based on the taxonomy of my 2002 book, The Restoration Economy.

The mixed-use community now known as Stapleton was built the 4000-acre brownfield that comprised the majority of the 4700-acre former Stapleton Airport site. The monumental process of repurposing, renewing and reconnecting (a good example of the 3Re Strategy in action) this vast site has been going on since 1988.

The mixed-use community now known as Stapleton was built the 4000-acre brownfield that comprised the majority of the 4700-acre former Stapleton Airport site. The monumental process of repurposing, renewing and reconnecting (a good example of the 3Re Strategy in action) this vast site has been going on since 1988.

With the catastrophic storm flooding in Houston and Florida again sounding the alarm about development patterns and ever-expanding impermeable urban surfaces in cities across the U.S., the sustainable design strategies of Stapleton stand out. Denver-based urban design and landscape architecture firm Civitas has been instrumental in the design of Stapleton, particularly in the articulation of its beloved parks and greenways, from the beginning.

The North Stapleton Open Space Plan for the newest neighborhoods north of I-70 won Civitas a 2017 ASLA Colorado merit award. A final centerpiece of the plan—–Prairie Meadows Park–—is scheduled to open spring of 2018. Now as the last of the developable acreage in Stapleton is being graded for construction, most of the community’s parks have already opened.

The North Stapleton Open Space Plan for the newest neighborhoods north of I-70 won Civitas a 2017 ASLA Colorado merit award. A final centerpiece of the plan—–Prairie Meadows Park–—is scheduled to open spring of 2018. Now as the last of the developable acreage in Stapleton is being graded for construction, most of the community’s parks have already opened.

With the double function as green space and drainage ways, “Stapleton Parks were designed to handle major storm events,” says Scott Jordan, Civitas principal and design lead for Stapleton’s open spaces. At a recent community meeting, a resident observed, “The system is working. When we’ve had heavy rains, our homes didn’t flood,” adding an emphatic “thank you.” And between storms, the creative drainage solutions provide myriad active outdoor uses, including a kid-friendly creek bed in Prairie Meadows Park.

With over 250 acres of recently opened parks and open spaces between I-70 and 56th Avenue, Civitas has taken the relatively flat site and created a series of strategic and sculptural landforms that naturally convey storm water in lieu of piping it underground.

With over 250 acres of recently opened parks and open spaces between I-70 and 56th Avenue, Civitas has taken the relatively flat site and created a series of strategic and sculptural landforms that naturally convey storm water in lieu of piping it underground.

“By using a natural and visible system of water conveyance, residents are offered an array of interactive experiences to better appreciate the role of water in the prairie landscape,” explains Jordan.

Further inverting the traditional people-first pattern of residential development, Civitas designed an integrated prairie-like landscape that restores pre-airport Front Range ecosystems through a series of interconnected, yet diverse, open spaces that provide residents an increasingly natural experience of the landscape. “The system was designed as a network of loops to put the parks in motion and enhance potential social interactions,” added Jordan.

On the plantings level, Civitas worked with national firm Great Ecology to calibrate seed mixes and plant species selections for each micro-climate and micro-topography – “not only creating experiences for humans, but also optimal growing conditions for plants to thrive,” according to Jordan.

On the plantings level, Civitas worked with national firm Great Ecology to calibrate seed mixes and plant species selections for each micro-climate and micro-topography – “not only creating experiences for humans, but also optimal growing conditions for plants to thrive,” according to Jordan.

This intertwined approach to living in the landscape will be further enhanced as development pushes northeast toward the Rocky Mountain Arsenal – establishing long-term sustainability and reducing consumption of one of the West’s most valued natural resources; water.

Known for delving into the history of a place to inform its future, Civitas looked to the original wetlands and sand dunes that comprised the indigenous Sandhills Prairie ecosystem long before jets and runways crisscrossed Stapleton Airport. By creating water conveyance paths throughout the area, natural water filtration systems are re-established while feeding the landscape and nurturing habitat corridors for birds and other wildlife.

Once completed, the 470-acre Stapleton open space system north of I-70 will introduce the most expansive native prairie grass landscape system within the Denver Parks network. And once established, the plants will no longer require irrigation, effectively reducing the project’s overall water needs by 70 percent.

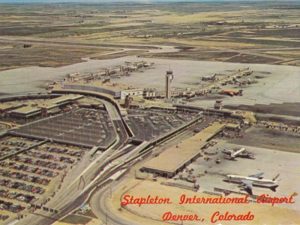

Here’s a bit more background: In 1995, when the opening of Denver International Airport meant the closing of Stapleton International Airport, Denver had the unique opportunity to transform 7.5 square miles of runways, concourses and terminals into a beautiful new community. It would be the largest urban in-fill redevelopment in the country and, to this day, one of the largest in-fill projects ever.

Here’s a bit more background: In 1995, when the opening of Denver International Airport meant the closing of Stapleton International Airport, Denver had the unique opportunity to transform 7.5 square miles of runways, concourses and terminals into a beautiful new community. It would be the largest urban in-fill redevelopment in the country and, to this day, one of the largest in-fill projects ever.

The building of Stapleton started as a collaborative effort by business leaders, civic officials and citizens who wanted to have a say in how Denver should grow. They spent countless hours and much of their own money creating what became known as the Green Book, the guiding principles for the redevelopment of Stapleton.

In 1998, the city of Denver selected Forest City to be the master developer and to make the vision of the Green Book a reality. In May 2001 the redevelopment began.

The idea was to take the best things about Denver’s classic neighborhoods – parks, welcoming front porches, ally-loaded garages, architectural diversity, tree-lined streets, more parks – and continue those urban patterns into new Denver neighborhoods. While applying some new thinking in the process. Like the use of water-wise landscaping and energy-efficient building standards on everything from homes to commercial spaces.

Over the last decade, the name “Stapleton” has become synonymous with an urban neighborhood that boasts award-winning parks, pools, schools and a diverse array of people, homes and lifestyles. But it wasn’t long ago, that “Stapleton” referred to something much different: an airport that no longer met the needs of its vibrant, growing city.

Over the last decade, the name “Stapleton” has become synonymous with an urban neighborhood that boasts award-winning parks, pools, schools and a diverse array of people, homes and lifestyles. But it wasn’t long ago, that “Stapleton” referred to something much different: an airport that no longer met the needs of its vibrant, growing city.

When Forest City Enterprises, Inc. broke ground for the redevelopment of Stapleton in 2001, it was the nation’s largest urban infill project at 4,700 acres. The vision was to take something that was no longer useable and give it a new purpose. As such, the concrete laden runways were transformed into tree-lined streetscapes, the parking structure became a sixth neighborhood site, and business travelers were replaced with thousands of happy residents. This transformation has helped make Stapleton a leading example of adaptive reuse in the U.S., and the nation’s 6th best-selling community, according to Robert Charles Lesser & Co. LLC (RCLCO). Through this thoughtful transformation of repurposed materials and spaces, a new identity for Stapleton emerged.

“For decades, the name ‘Stapleton” had been known throughout the nation and later the world as Denver’s airport,” said Tom Gleason, vice president-public relations for Forest City Stapleton, Inc. “Today it represents a mixed use neighborhood that celebrates the diversity of its residents and amenities that reflect the best of urban living.”

Over the course of the past dozen years or so, Stapleton has become a true urban oasis. The estimated 20,000 residents are at the heart of this success, helping create the spirit, personality and quality of life that are palpable just by walking down the street.

Over the course of the past dozen years or so, Stapleton has become a true urban oasis. The estimated 20,000 residents are at the heart of this success, helping create the spirit, personality and quality of life that are palpable just by walking down the street.

“We all believed the vision behind the new community of Stapleton was to become an extension of Denver…whether it was by continuing the neighborhood grid system, building on its long history of incredible parks or embracing the reuse of the former Stapleton International Airport as our location,” said John Lehigh, President of Forest City Stapleton.

Over the years, the community of Stapleton has continued this history of organic naming throughout the area. It embraced the neighborhood nicknames given by residents that expressed their individual identity. These names later became the foundation of Stapleton’s collection of neighborhoods, including Southend, Eastbridge and Central Park West to name a few—with the most recent new neighborhood, Willow Park East, being named for its city soul and prairie heart.

Much like “Stapleton”, each neighborhood embraces and references its unique location in the community. Moreover, the name of each park is derived from the geographic place it is near. This helps orient the community and its residents to their location. Examples are Central Park (the 80-acre centerpiece of the community), the ecologically-restored Westerly Creek (adjacent to the creek), and Bluff Lake, which is adjacent to the Bluff Lake Nature Center.

Much like “Stapleton”, each neighborhood embraces and references its unique location in the community. Moreover, the name of each park is derived from the geographic place it is near. This helps orient the community and its residents to their location. Examples are Central Park (the 80-acre centerpiece of the community), the ecologically-restored Westerly Creek (adjacent to the creek), and Bluff Lake, which is adjacent to the Bluff Lake Nature Center.

Affordable housing, both for rent and sale, fitting seamlessly into the neighborhoods. And perhaps the most sustainable idea of them all: a pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use environment with everything residents need is just a short walk or bike ride away.

Two decades later, Stapleton stands as a global model of urban redevelopment. Buzzing with bike races, farmers markets and concerts in the park, Stapleton now thrives at a grassroots level, thanks to residents and business owners who each add their own touch. It has become a place that’s far better than anyone could have planned.

Despite all this newness, Stapleton also continues to embrace its heritage as a historic airport. The community pays homage to its aviation history through the naming of its pools including Aviator, Puddle Jumper, F-15, Jet Stream and Runway 35. In other words, they achieved this spectacular revitalization by repurposing, renewing, and reconnecting all the existing “restorable assets”—natural, built, and cultural—as recommended in the new Resilience Success Guide.

All images provided by Civitas.