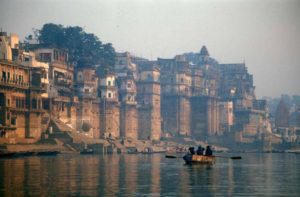

It’s been a long, long time since I (Storm) visited Varanasi, India (still called by the British name, Benares, when I was there). Yet my memories of the iconic ghats and the long-suffering Ganga River (known as the Ganges to most English speakers) are still remarkably fresh in my mind. Such is the power and intensity of the experience.

The Ganga flows 2525 km (1569 miles) through the nations of India and Bangladesh. The river originates in the western Himalayas in the Indian state of Uttarakhand, and flows south and east through the Gangetic Plain of North India into Bangladesh, where it empties into the Bay of Bengal. It’s the third largest river in the world, measured by water volume.

The Ganga is the most sacred river to Hindus, and is a lifeline to millions of Indians who live along its banks and depend on it for their daily needs. Indeed, it supports almost 10% of the world’s population.

The Ganges was ranked as the fifth most polluted river of the world in 2007. Pollution threatens not only humans, but over 140 fish species, 90 amphibian species, and the endangered Ganges river dolphin. The levels of fecal coliform from human waste in the waters of the river near Varanasi are more than 100 times the Indian government’s official limit.

The Ganges was ranked as the fifth most polluted river of the world in 2007. Pollution threatens not only humans, but over 140 fish species, 90 amphibian species, and the endangered Ganges river dolphin. The levels of fecal coliform from human waste in the waters of the river near Varanasi are more than 100 times the Indian government’s official limit.

The Ganga Action Plan was launched by Shri Rajeev Gandhi, the then-Prime Minister of India, on January 14, 1986. It was an environmental restoration initiative designed to clean-up the river, but has been a major failure thus far. This is reportedly due to a combination of corruption, lack of technical expertise, poor environmental planning, and lack of support from religious authorities.

Now, the innovative Delhi-based architectural practice Morphogenesis has presented an urban intervention for sustainable restoration of the historic interface between humans and the river. The firm is known as a world-leader in net zero energy and sustainable design.

Now, the innovative Delhi-based architectural practice Morphogenesis has presented an urban intervention for sustainable restoration of the historic interface between humans and the river. The firm is known as a world-leader in net zero energy and sustainable design.

Yet, the Ganga is dying. The issues that the river faces today are environmental, social, hydrological and infrastructural. Whilst all are important, the most critical one to tackle is the Ganges’ environmental degradation. The Ganges probably carries more sewage than any other water body in the world today. 260 million litres of industrial waste pours into it every day, more than the output of several nations. It carries pesticides and is highly contaminated by ritual waste and human remains. While the Ganges provides life to a significant population, the number of waterborne deaths it causes due to pollution, at a conservative estimate, is 600,000 per year.

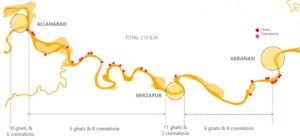

As architects and advocates for this “River in Need” wanted to design in an environmentally contextual and culturally sustainable approach; one that recognizes that the ultimate goal to close the circle of life around the Ganges is to become one with the river. Morphogenesis aims to design the crematoria and actual pyre, to reduce the amount of wood required to 30%, thereby also reducing the cost of the cremation, which is often higher than the annual income of the household.

As architects and advocates for this “River in Need” wanted to design in an environmentally contextual and culturally sustainable approach; one that recognizes that the ultimate goal to close the circle of life around the Ganges is to become one with the river. Morphogenesis aims to design the crematoria and actual pyre, to reduce the amount of wood required to 30%, thereby also reducing the cost of the cremation, which is often higher than the annual income of the household.

There has to be a sensitive handling of all the various rituals that the Ganges is part of. A large scale vision and small scale execution is key to a successful implementation. Whilst looking at rejuvenating the usage of the river, a prime design concern has been dealing with the erosion of the river bank, which is addressed by researching and redesigning traditional vernacular learning of the way the water edge was treated, such as ghats (a flight of steps leading down to the river), which lent themselves to stabilizing the river edge along with providing the interface for human and water engagement.

The provision of ritual tanks and various other urban design elements – platforms for discourse, platforms for cremation – are such that all the acts can be performed using the water in a controlled way, hence introducing the potential for cleaning of the polluting elements. Morphogenesis has looked at reforestation with plants that are resilient, and work with varying flood levels on the ghats. With increasing densification of Indian towns and cities, there is greater need for space required for urban interaction, community building and for public engagement.

The provision of ritual tanks and various other urban design elements – platforms for discourse, platforms for cremation – are such that all the acts can be performed using the water in a controlled way, hence introducing the potential for cleaning of the polluting elements. Morphogenesis has looked at reforestation with plants that are resilient, and work with varying flood levels on the ghats. With increasing densification of Indian towns and cities, there is greater need for space required for urban interaction, community building and for public engagement.

Morphogenesis aims to turn the city inside out by sustainable development of this riverside urban frontage. These ghats when redeveloped will not only serve their traditional ritualistic purposes but also function as urban spaces for discourse and dissemination of knowledge. In that vein these spaces are designed to be Wi-Fi enabled, and in keeping with sustainability metrics, they will almost entirely run off solar power. Simple technological yet historic innovations like hume pipes are introduced to stabilize the edges.

In terms of design strategies, locally available porous materials which allow water to percolate through are used. Almost all structures are proposed to be made of brick because of the good quality soil available in the region, and that it is low maintenance and self-cleaning with the weather.

Chaupals (seating under the shade of trees), which has been the age old gurukul method of teaching, are reintroduced as shade canopies for social activity. Smart ghat columns provide additional framework for increasing shaded area besides fulfilling essential functions of providing drinking water, Internet connectivity and as solar power stations. Ventilation has been taken care of, with all structures lifted, which is ideal for hot climate construction.

Chaupals (seating under the shade of trees), which has been the age old gurukul method of teaching, are reintroduced as shade canopies for social activity. Smart ghat columns provide additional framework for increasing shaded area besides fulfilling essential functions of providing drinking water, Internet connectivity and as solar power stations. Ventilation has been taken care of, with all structures lifted, which is ideal for hot climate construction.

Solar panels form most of the lifted roofs enabling greater energy efficiency. Piers capable of sustaining water transport up and down the river have been designed.

Morphogenesis says that its social agenda is to respond to a river in need, a river that feeds one of the highest densities of population in the world, and in its resurrection, not only bring back the glory of the past but also create potential for the future that sustains the Ganges’ intrinsic importance in the lives of future generations.

All images courtesy of Morphogenesis unless otherwise credited.