It’s no secret in the U.S. that big box stores, shopping malls and strip centers—in other words, sprawl-based retailers—are closing right and left. Online shopping and downtown revitalization are the two key causes in most cases. Many industries—not just retail—have turned the name “Amazon” into a verb, as in “our industry is being Amazoned.”

But this fast-growing inventory of “greyfields” (non-polluted abandoned sites) is being met by the rapid growth of innovative redevelopers who are using the new “3Re Strategy” to repurpose, renew, and reconnect these idle properties.

It’s a trend that has already had some publicity in popular media. The January 2015 issue of Fast Company magazine, for instance, had an article titled “Unconventional Ideas For Using Empty Office Buildings“. It included such suggestions as using them to hold community meetings (such as book clubs), coworking space (kind of like a commercial AirBNB), nightcare (daycare for parents who work at night), exercise studios, and (my favorite): homeless shelters.

Let’s arbitrarily choose a single day in 2018 for a small, representative sampling of the current rapid growth of this trend: March 20 will do nicely.

In Clay, New York, for instance, it was announced on March 20 that a local real estate firm is partnering with the new owner of the former Macy‘s store at the Great Northern Mall to redevelop the space with restaurants, stores and entertainment.

Syracuse-based Acropolis Development was been selected by Lionheart Capital to oversee the leasing and management of the vacant 88,000-square-foot store at the front of the mall. Macy’s closed the store in April 2017 as part of a plan to shutter 100 of its 730 stores nationwide.

Photo courtesy of Patch.com

Also on March 20, 2018, it was announced in Toms River, New Jersey that the largest mall developer in the U.S. is apparently shifting its growth strategy from building new malls to repurposing and renewing those it already has. Simon Property Group—whose spectacular growth since 1960 triggered the devitalization of thousands of American downtowns—is the owner of the Ocean County Mall. They plan to redevelop the vacant Sears building.

In the fourth quarter of 2017, Indianapolis-based Simon acquired full control of five Sears stores at its malls, including the one at Ocean County Mall. Now with full ownership, Simon will have the ability to chart the future course of the building. “We are extremely excited to get these spaces back and redevelop the space into higher and better uses,” Simon said in a statement. “The redevelopment at Ocean County Mall will be a great positive for the property with more terrific options for our shoppers.”

This is the least-innovative form of the repurposing and renewal (adaptive reuse) trend, in that the facilities will remain primarily retail. But both the ownership model and the nature of the commerce—from big-box to small-scale—is changing.

Of course, greyfields aren’t just dead retail facilities. They can be office buildings also. Here again, such properties—which used to remain vacant for years or even decades in the recent past—are now being snapped-up by redevelopers. But not all of these buildings are architectural gems, or even well built. Sometimes, it’s the property beneath them that needs to be repurposed and renewed, not the structures.

Again on March 20, 2018, the Fairfax County (Virginia) Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a project by private redeveloper Renaissance Centro to replace a three-story office building built in the late 1980s with a 20-story condominium high rise in Reston, Virginia.

The project will include 150 residential units, including 24 for-sale, workforce housing units and 24 bonus units, built on top of an underground parking garage.

Speaking of Fairfax County, I (Storm) should point out that this new wave of redevelopers includes public players, too.

Fast-growing Fairfax County has been running out of space to build new schools. Recognizing that office buildings are often in easily-accessible locations, they have been converting some of their vacant commercial properties into public schools and county offices. They’ve also made changes to their policies that make it easier for private redevelopers to repurpose office space for non-commercial uses.

Despite its wealth, Fairfax County has been over-built commercially: it’s grappling with over 18 million square feet in empty office space. In response, the county recently approved changes to their land use plan to more easily allow these vacant buildings to be turned into other uses, such as apartments, schools, co-working spaces or food incubators.

The Board of Supervisors signed-off on the change during its December 5, 2017 meeting. The action allows these offices to be turned into other uses without requiring a site-specific change to the land use plan. To be eligible, buildings must be in areas planned for mixed use or industrial development, like Tysons, Dulles and Merrifield, and they need to meet specific guidelines to ensure the new uses fit in with the surrounding development.

Most buildings proposed to be repurposed will need rezoning approval by the board. This process incorporates opportunities for community input, including public hearings. County officials also retain the right to require a reuse project to go through a site-specific land use change.

Rendering of interior of Bailey’s Upper Elementary School courtesy of Cooper Carry.

If more cities and counties were to follow Fairfax County’s lead, and redesign their local policies and zoning ordinances around the 3Re Strategy to encourage the repurposing, renewing, and reconnecting of their natural, built and socioeconomic assets, we would see an even faster blossoming of community revitalization.

Fairfax County might have been inspired by its neighbor, Arlington County (where I live). Back in July of 2014, the Arlington County Board approved a plan by the national real estate development firm Vornado to convert a vacant 1960s office building in Crystal City into innovative residential apartments that will offer shared amenities and a unique floor-by-floor “neighborhood” culture.

The former office building, known as Crystal Plaza 6, is part of the six-building Crystal Plaza Development. Its last federal tenant left earlier that year.

Vornado created the project in partnership with WeWork, a national company with co-working offices in major metropolitan areas across the country. The company currently has three offices in the Washington, D.C. area that provide co-working office space, benefits and support.

The Crystal City project will be WeWork’s first residential building, bringing the same benefits of co-working – shared amenities, a sense of community and opportunities for collaboration – to a residential building. The project will offer an entirely new type of apartment living within walking distance of the Crystal City Metro Station, several bus stops and Capital Bikeshare stations, and will serve as a model for adaptive reuse of an outdated building until redevelopment can occur.

“This temporary conversion of an aging, vacant office building into an innovative live-work space is an example of how we continue to reinvent Crystal City as a more attractive, vibrant place that will attract more entrepreneurs and tech workers,” said then-Arlington County Board Chair Jay Fisette.

The County Board vote 4 to 0 to approve the major site plan amendment for 2221 S. Clark Street, changing the use from office to residential. The 12-story building will have 252 units, many of them 360 square feet or less, and several shared two-story “neighborhoods” with expansive common areas. The neighborhoods will be connected by staircases and feature commercial-grade kitchens, dining areas and shared community spaces.

WeWork has a 20-year lease on the building, which is eventually slated to be redeveloped by 2050 as part of the Crystal City Sector Plan, with realignment of S. Clark/Bell Street.

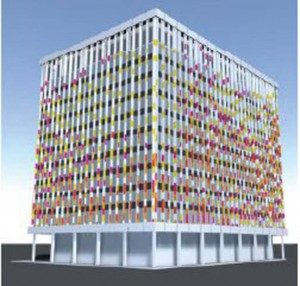

The building—built in 1965 and now obsolete by modern office standards—was gutted. The exterior remained largely intact, although it’s been updated with an experiential exterior color application that changes as one moves around the building.

The colors work quite nicely to enliven the concrete-intensive nature of Crystal City: my wife and I remarked on it several times before I learned what the project was. The project included streetscaping, sidewalk improvements, and outdoor areas including, play and lounge zones and a community garden. The building has 154 parking spaces and 86 interior and 8 exterior bike parking spaces.

The WeWork project joins other innovative initiatives, such as the Crystal Tech Fund, TechShop, and Crystal City Design Lab, that are transforming Crystal City into a community for growth tech companies, small businesses and entrepreneurs.

The site plan amendment was reviewed at the Site Plan Review Committee (SPRC) meeting on May 12, 2014, by the Transportation Commission at its hearing on June 30, 2014, and by the Planning Commission on July 7, 2014.

Crystal Plaza 6 is one of eight buildings which together comprise the mixed-use, multiple building Crystal Plaza site plan, which falls under the Crystal City Sector Plan. The site plan was approved in 1963, and most of the buildings were constructed in the 1960s. Today, the site plan has approximately 785,572 square feet of site area and is developed with 989,707 square feet of office, 196,610 square feet of retail, and 1,143,326 square feet of residential. Plaze 6 is approximately 157,670 square feet.

The County Board adopted the Crystal City Sector Plan in 2010. The 50-year long-range plan is the result of extensive work with the community, including more than 90 public meetings over a four year period. The plan embodies the community’s vision to transform the Crystal City area by encouraging new development through density and other incentives, improving the streets, sidewalks and other public infrastructure, upgrading open space and increasing transit options.

Arlington might have been inspired by a paper (link below) titled “Adaptive reuse of office buildings: Opportunities and risks of conversion into housing“, published by researchers at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands back in March of 2014.

The Abstract reads: “Conversion into housing is a way of adapting and reusing vacant office buildings. Former research has shown possibilities for this type of conversion, and has delivered instruments for determining the conversion potential of vacant offices. While adaptation and renovation of outdated offices can prove to be a successful real estate strategy, conversions into housing still take place only on a small scale. There are several reasons for this, like uncertainty about financial feasibility, and little knowledge about the opportunities and risks of building conversions. This paper reveals drivers for office-to-housing conversions and conversion opportunities and risks, based on a review of international literature and a cross-case study of 15 buildings in the Netherlands which were converted from offices to housing. The findings show that various legal,financial, technical, functional and architectonic issues define the opportunities and risks of building conversions. These insights can be used to support decision making on how to deal with vacant office buildings.”

Between Fairfax County and Arlington County, Northern Virginia is showing communities suffering from an excess of commercial development that they don’t need to passively wait for market forces to bring these structures back to life. Innovative public leadership can accelerate the process, and do so in a way that has more social benefits than ordinary office rentals usually provide.

Arlington was the birthplace of the “smart growth” movement in the United States, and was the first local government in the country to require that all new public buildings be LEED-certified. Now, it seems to have been of the forefront of the trend of community-led adaptive reuse of vacant commercial space as a revitalization strategy. I’m proud to call it home.

Featured photo by Storm Cunningham shows Bailey’s Elementary School in former vacant Fairfax County office building.

See interior photos of Bailey’s Elementary School on Architizer.

See Macy’s article in Syracuse.com

See Sears article in USA Today.