Ethiopia is suffering from severe drought, but there is water in Gergera. 20 years of restoring its hills and river valley has brought life back to this area of the Tigray region in the country’s far north.

The work has been painstaking, complex and multidimensional and continues to this day. But the hard-won results offer up two key lessons. We know now that landscape restoration in drylands hinges on water management. And we know, just as importantly, that restoration can create a base for better livelihoods and jobs for youth who formerly left in droves.

Government ministers visited the revitalized watershed on May 31, 2017 after signing a Memorandum of Understanding to establish a National Agroforestry Platform to support climate-resilient green growth and transformation. Over 40 prominent figures attended, including ministers of state Kaba Urgesa and Gebregziabher Gebreyohannes, Wubalem Tadesse of the Ethiopian Environment and Forest Research Institute, Fassil Kebede, adviser to the minister of agriculture, and Eleni Gabre Madhin, founder of Ethiopia’s commodity exchange and representatives of embassies, development agencies, and civil society groups such as Oxfam, Farm Africa, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and Packard.

Government ministers visited the revitalized watershed on May 31, 2017 after signing a Memorandum of Understanding to establish a National Agroforestry Platform to support climate-resilient green growth and transformation. Over 40 prominent figures attended, including ministers of state Kaba Urgesa and Gebregziabher Gebreyohannes, Wubalem Tadesse of the Ethiopian Environment and Forest Research Institute, Fassil Kebede, adviser to the minister of agriculture, and Eleni Gabre Madhin, founder of Ethiopia’s commodity exchange and representatives of embassies, development agencies, and civil society groups such as Oxfam, Farm Africa, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and Packard.

The World Agroforestry Centre has been running a related 3-year research project in sub-Saharan Africa to restore degraded soils. The project runs from April 2015 to April 2018. Thegoal of the project is to reduce food insecurity and improve livelihoods of poor people living in African drylands by restoring degraded land, and returning it to effective and sustainable tree, crop and livestock production, thereby increasing land profitability and landscape and livelihood resilience.

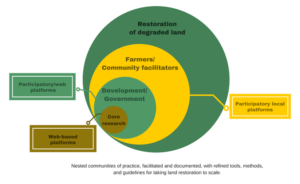

The project is designed to operate through bringing key partners from the public and private sectors, across research, extension, market, and governance institutions to work together in an iterative co-learning cycle, where options are tested against context and lessons learnt are fed back into the cycle.

This requires capacity strengthening within these key institutions and locally, nationally and regionally to facilitate interaction amongst them. The capacity strengthening is achieved by doing (the co-learning cycle is a capacity strengthening strategy that is propelled by the learning achieved through using planned comparison of options by context, rather than only trying best bets over narrow ranges of context). The approach will create durable communities of practice able to better use resources to make impact on land restoration at scale.

During the recent European Development Days held on June 7-8, 2017 in Brussels, Belgium, the Joint Research Commission of the European Commission led a session on sustainable soil management in Africa. Panelists drew from different organizations including the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and University of Leuven.

Their discussion focused on solutions to large-scale adoption, both at policy and practical levels, of key land restoration options including integrated soil fertility management alongside practices such as intercropping and agroforestry. Scientists from ICRAF presented compelling evidence on how soil restoration can contribute to improved food security and livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa.

“Land degradation in the drylands of Sub-Saharan Africa continues to threaten food security and livelihoods,” said Leigh Winowiecki, a soil scientist at ICRAF. “To that end, sustainable soil management is key to restoration of degraded land to transform lives and landscapes.” Her presentation looked at the role of sustainable soil management for restoration of degraded land in East Africa and the Sahel, highlighting activities from the IFAD/EC-funded project ‘Restoration of degraded land for food security and poverty reduction in East Africa and the Sahel: taking successes in land restoration to scale“.

“Land degradation in the drylands of Sub-Saharan Africa continues to threaten food security and livelihoods,” said Leigh Winowiecki, a soil scientist at ICRAF. “To that end, sustainable soil management is key to restoration of degraded land to transform lives and landscapes.” Her presentation looked at the role of sustainable soil management for restoration of degraded land in East Africa and the Sahel, highlighting activities from the IFAD/EC-funded project ‘Restoration of degraded land for food security and poverty reduction in East Africa and the Sahel: taking successes in land restoration to scale“.

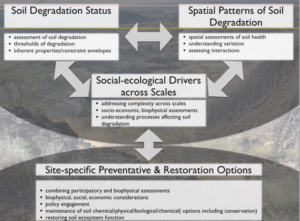

When considering options for land restoration initiatives, it is important to understand what works where for whom. Variability in social, cultural, economic and biophysical environments greatly influence the results of such initiatives. ICRAF has developed tools that map soil organic carbon and soil erosion prevalence to provide relevant soil information aimed at land restoration interventions.

“We are working with development partners in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mali and Niger to implement and monitor on-farm land restoration interventions such as farmer-managed natural regeneration, soil and water conservation, micro-dosing of fertilizers, tree planting and agroforestry, use of Zai pits [small water harvesting pits] on farms and pest control,” added Winowiecki.

“We need to understand the systems we work in to design effective interventions to restore land health and reverse land degradation,” said Tor-Gunnar Vagen, who leads ICRAF’s GeoScience Lab. “There are different ways to understand how the soil properties and their spatial distribution determine sensitivity to land degradation using tools such as tools such as the Land Degradation Surveillance Framework and earth observation. Assessments need to be spatially explicit and at scales relevant to farmers and land managers.”

See article by Cathy Watson in The Guardian.