Akron is the fifth-largest city in Ohio, and the 119th largest city in the United States, with a 2010 population of 703,200. It’s located on the about 39 miles (63 km) south of Lake Erie, on the Little Cuyahoga River.

It was co-founded in 1825 by Simon Perkins and Paul Williams, primarily because it was in strategic position at the summit of the developing Ohio and Erie Canal. That canal was short-lived, due to the rapid onslaught of the more-efficient rail alternative. But that was the only blow affecting the city’s fortunes.

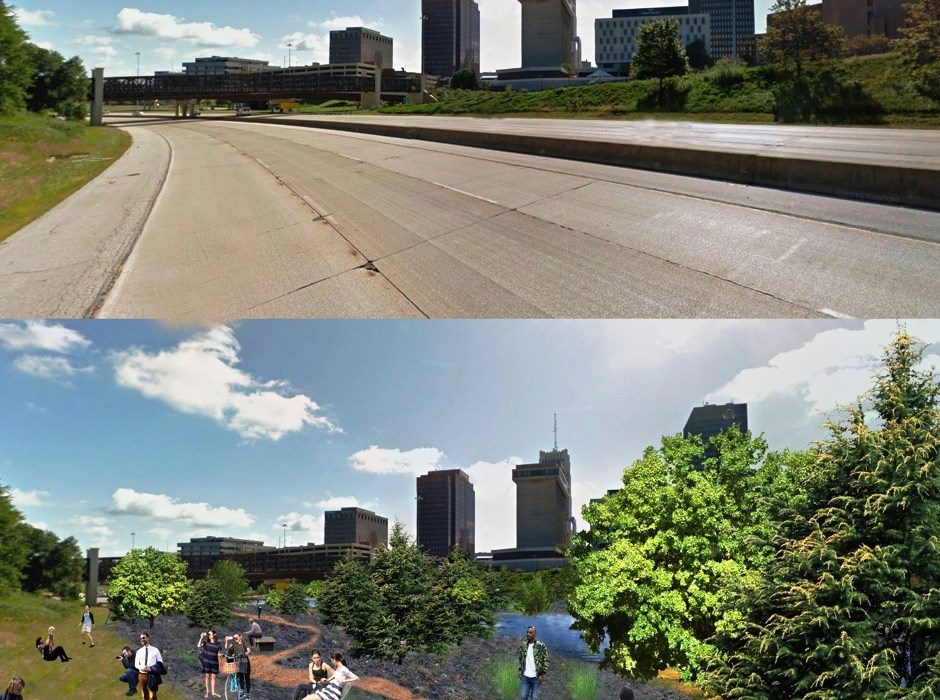

The same decline of heavy manufacturing that doomed so many “Rust Belt” cities in America hurt Akron badly. But so did their planners (another characteristic they share with other declining cities). In the annals of bad highway planning, Akron’s Innerbelt—a, a sunken six-lane artery built in the 1970s, deserves special mention.

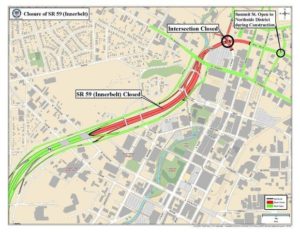

Never completed, the 4.5-mile long freeway was envisioned as a connection between central Akron and the peripheral expressways that were sucking residents out of the inner city to the devitalizing suburbs.

Instead, the Innerbelt devastated historic black neighborhoods, cordoned off downtown from westbound foot traffic, and became a notoriously underused “road to nowhere” as Akron’s population dwindled to fewer than 200,000 souls—two-thirds of its 1960s peak.*

That narrative is familiar in so many American cities, where bad–often racist–urban highway planning has long been the norm, not the exception.

As readers of REVITALIZATION are well-aware, there’s a global movement underway to repurpose and renew inappropriate and/or obsolete infrastructure, with the aim of reconnecting and revitalizating the neighborhoods it once severed and devitalized.

In Akron, one of the proposals is to repurpose the unused portion of the highway as a heavily-forested public park. They are testing the concept on a small scale: Armed with a $214,420 grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation‘s 2017 Knight Cities Challenge, artist Hunter Franks plans to transfor two acres of abandoned highway with lush trees and attractive light installations, and will activate it with public events that are easily accessible to the surrounding neighborhoods.

The Knight Cities Challenge sought new ideas from innovators who will take hold of the future of American cities. The challenge is currently closed, but for three years it invited applicants from anywhere to tell us their ideas for making the 26 Knight communities more vibrant places to live and work.

The challenge was designed to help spur civic innovation at the city, neighborhood, and block levels, and all sizes in between. In particular, they hoped to generate ideas that focus on one or all of three key drivers of city success: attracting talented people, expanding economic opportunity, and creating a culture of civic engagement.

Of course, reconnecting neighborhoods by updating the infrastructure that once divided them isn’t simple: The wave of gentrification sparked by New York City’s High Line offers a case study in the potential pitfalls of adaptive reuse projects, and concerns about rising property values pricing out longtime residents are motivating resistance to the Denver highway cap.

But the housing market in Akron is a far cry from either of those cities; with median home values hovering at a scant $63,000, displacement is not the concern at hand. As the city’s population continues to decline, Akron leaders are exploring dozens of strategies to remake the city into a more attractive place to settle.

Feature image of before-after repurposing Innerbelt by Hunter Franks/Knight Cities Challenge.