Humans killed off all the major predators on British Columbia’s Gulf Islands a century ago.

Now that there are no cougars, wolves, or bears to keep the raccoons in check, the masked marauders have run rampant.

The raccoons eat everything they find, including songbirds, crabs, and fish. “They’re essentially out night and day, eating all the time, and having a pretty dramatic impact on the entire ecosystem,” said Justin Suraci, an ecologist with the Raincoast Conservation Foundation.

The populations for many of the islands’ native species have declined by as much as 90 percent as a result. The researchers hypotesized that they might be able to reduce the raccoons’ foraging by reintroducing at least the fear of predators, if not the predators themselves.

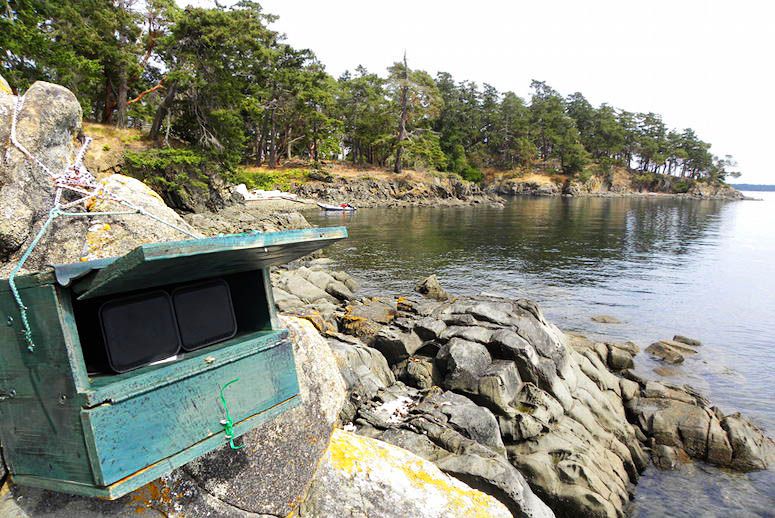

They installed a series of loudspeakers, and played the sound of barking domestic dogs. It worked, although the scientists acknowledge that the effect will wear off with time, as the raccoons start to realize there aren’t any actual dogs.

By the end of the researchers’ experiment—documented this week in a study published in the journal Nature Communications—the raccoons’ prey had dramatically bounced back. Intertidal crab populations increased by 97 percent, fish increased by 81 percent, and the red rock crab population grew by 61 percent.

Abstract from Nature Communications report: The fear large carnivores inspire, independent of their direct killing of prey, may itself cause cascading effects down food webs potentially critical for conserving ecosystem function, particularly by affecting large herbivores and mesocarnivores. However, the evidence of this has been repeatedly challenged because it remains experimentally untested.

Here we show that experimentally manipulating fear itself in free-living mesocarnivore (raccoon) populations using month-long playbacks of large carnivore vocalizations caused just such cascading effects, reducing mesocarnivore foraging to the benefit of the mesocarnivore’s prey, which in turn affected a competitor and prey of the mesocarnivore’s prey.

We further report that by experimentally restoring the fear of large carnivores in our study system, where most large carnivores have been extirpated, we succeeded in reversing this mesocarnivore’s impacts. We suggest that our results reinforce the need to conserve large carnivores given the significant “ecosystem service” the fear of them provides.