Set in the foothills of mountains, surrounded by greenery and dotted with buzzing cafés, visitors to Germany’s Lusatian Lake District may have little idea of the scarred landscape beneath the peaceful waters.

Thirty years ago, the now-peaceful villages sat alongside the noise and dust of a major coal mine.

At its height, thousands of people were employed in Lusatia’s mines. Numerous pits were dug to extract lignite – a poor-quality form of coal – to fire Germany’s power stations.

Many villagers were driven away as the earth was carved up to access the natural resources – 26,0000 people were relocated to make way for the mines.

But with the reunification of Germany, most of the mines were closed down. The former industrial site fell into decline. And the marred landscape was a source of pollution.

Now, some serious investment in the region has created Europe’s largest artificial lake complex. An hour and a half southeast of Berlin, the area now attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists a year.

More than 20 lakes are connected by a cycle network, providing a venue for watersports, horse riding, quad biking, fishing and diving. There are cafés, restaurants and hotels.

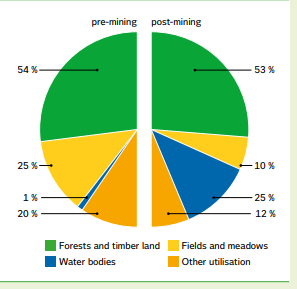

Millions of trees have been planted to restore great forests, and many hectares of agricultural land have been created on former mining dumps. There are even vineyards.

Tourists can visit former mines, slowly being reclaimed by wildlife, and a former power plant is now home to art exhibitions and a music venue.

A Scarred Landscape

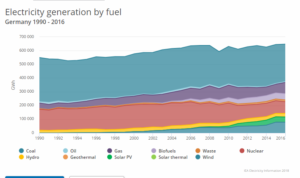

But with coal still lighting a large number of Germany’s homes, some of the mines in the region are still active. And a fact-finding mission by the European Parliament in 2018 concluded that the environmental scars of the region’s industrial past are still evident.

There are concerns that chemicals making their way into rivers threaten Berlin’s drinking supply. Some areas are suffering drought as a result of ground water levels dropping around the mines and there is the risk of ground movement affecting buildings.

Poisonous sludge in waterways risks killing off fish and insects and jeopardizing nature conservation.

Germany plans to shut down its coal industry by 2038 – a shift that is likely to come at a cost of tens of billions of euros.

In recent years, renewables have increased in the electricity generation mix. Wind power was the second largest energy source last year and for most of the year made up a greater power source than hard coal or nuclear, according to solar energy research body the Fraunhofer Institute.

Featured photo of an old mine converted to a touris destination courtesy of REUTERS / Wolfgang Rattay.

Our thanks to REVITALIZATION subscriber Julia Oxarango-Ingram for alerting us to this article.

This article by Charlotte Edmond originally appeared on the website of the World Economic Forum. Reprinted here (with minor edits) by permission.

See related National Geographic article.

Learn more about Lusatia’s economic revival based on restoring and repurposing old mines (PDF).