Not very long ago, the glitzy area now referred to as Nuevo Polanco was a grubby warehouse and factory district in the west-central part of Mexico City.

The area’s fortunes started reversing when the high-end Antara Polanco shopping center was opened in 2006, on the site of a former General Motors manufacturing plant.

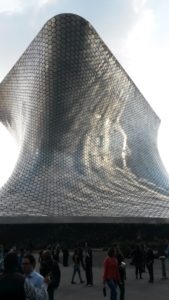

When most tourists think of Nuevo Polanco, the first thing that comes to mind is the spectacular Museo Soumaya, a private museum designed by the Mexican architect Fernando Romero. It helped turn this tired old light-industrial district into one of the hottest new neighborhoods in the city center, much as Frank Gehry‘s Guggenheim Museum became emblematic of Bilbao, Spain‘s revitalization. NOTE: the Guggenheim didn’t cause the city’s turnaround, despite what “starhitects” like to claim. The true story of Bilbao’s impressive urban regeneration success was told in a case study in the 2008 book, ReWealth (McGraw-Hill).

Museo Soumaya is a non-profit cultural institution that actually has two museum buildings in Mexico City: Plaza Carso (in Nuevo Polanco) and Plaza Loreto.

It has over 66,000 works from 30 centuries of art including sculptures from Pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica, 19th- and 20th-century Mexican art and an extensive repertoire of works by European old masters and masters of modern western art such as Auguste Rodin, Salvador Dalí, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, and Tintoretto, considered one of the most complete collections of its kind.

The museum is named after Soumaya Domit, who died in 1999, and was the wife of the founder of the museum, billionaire Carlos Slim. [Note: One of the world’s richests men, Slim made his fortune by using corrupt politicians to gain a private monopoly on telephone service in Mexico. For almost two decades, TelMex charged some of the world’s highest rates to some of the world’s poorest people. It also greatly undermined this beautiful nation’s economic development by protecting its antiquated technology from competition: a monopoly that is finally being broken.]

Museo Soumaya was attended by over a million people in 2013, making it the most visited art museum in Mexico, and the 56th in the world that year. In October of 2015, the museum welcomed its five millionth visitor.

Museo Soumaya has company right across the railroad tracks in Nuevo Polanco: Museo Jumex.

Museo Jumex features art works by Damien Hirst, Andy Warhol, Gabriel Orozco, Cy Twombly, Jeff Koons, Andreas Gursky, Darren Almond, Tacita Dean, Olafur Eliasson, Martin Kippenberger, Bruce Nauman, and Francis Alÿs.

Museo Jumex is thus devoted to contemporary art. Its aim is not only to serve a broad and diverse public, but also to become a laboratory for experimentation and innovation in the arts.

Built in November of 2013, the building–with its distinctive sawtooth form–was designed by David Chipperfield Architects.

Rather charmingly, freight trains still make their way (very slowly) through Nuevo Polanco, helping to connect all this shiny newness to its very recent gritty industrial past.

Nuevo Polanco’s revitalization is so successful that it is attracting major employers away from the sprawl areas, and back into the city center.

Mexico’s largest financial institution, BBVA Bancomer, moved its Mexico City operations center from a Brutalist building in a leafy suburb to Parques Polanco, the old neighborhood that’s being reborn due to its being next to Nuevo Polanco.

Bancomer hired Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) to design a building that would help reinvigorate the company.

The Bancomer Operations Center is an architectural landmark that consolidates and repositions BBVA Bancomer’s physical presence in Mexico City. Rising 135 meters, the state-of-the-art, environmentally sustainable building raises the bar for new commercial projects in Mexico’s capital and elevates the profile of BBVA Bancomer in Latin America.

As part of a planned development, the Operations Center relates to its dense urban context through massing and scale. The building is conceived as a “vertical city,” a bundle of volumes shifted at their intersections to create points of articulation. It is filled with amenities including cafeterias, lounges, outdoor terraces, and meeting spaces to reinforce a sense of community. The building’s scale and visual dynamism contribute to the area’s pedestrian character, while creating an interior environment that supports productivity.

Certified LEED®-NC Gold, the Operations Center elevates the level of building quality and performance in Mexico City’s commercial marketplace. A host of energy- and water-saving features are integrated in the design. Its sophisticated glass facade is wrapped by a screen of staggered vertical louvers that are calibrated to the angle of the sun, in order to reduce solar heat gain while maximizing views and filtering daylight.

Located next to a verdant open space, the tower provides a commercial anchor for the neighborhood’s mixed-use master plan. The project has spurred improvements to the public realm, and residential and retail development has increased in the surrounding area.

“I think the big lesson here is that office buildings today are not just about desks, efficiency, and packing people in. They’re much more about lifestyle and amenities,” SOM design partner Gary Haney says. “When you’re competing for a high-end workforce, these things aren’t just nice—they’re necessary.”

BBVA invested an additional $8.6 million beyond the cost of the building to engage the changing neighborhood: $4.4 million of that went toward direct community development, such as the planting of 355 trees. “It became a real outreach, way beyond the confines of the site,” Haney says. But the architecture also contributes.

Enclosing it with an elegantly shaded skin of aluminum and high-performance glass, SOM designed the building, on target for LEED Gold certification, to minimize its impact on the area’s infrastructure: solar water heating, daylighting, and a cogeneration plant reduce its energy consumption and prevent it from burdening the local power grid; water-efficient fixtures, on-site gray/blackwater treatment, and rainwater harvesting protect the city’s water supply and sewers.

On November 11, 2016, BBVA Bancomer Operations Center was selected to receive a 2016 Premio Nacional from the Instituto Mexicano del Edificio Inteligente y Sustentable (Mexican Institute of Intelligent and Sustainable Building).

The award was presented on November 28, 2016, at the Alcázar del Castillo de Chapultepec in Mexico City.

All this good news being said, Nuevo Polanco has had its problems, and its detractors. One problem is gentrification: city officials apparently put little attention on creating affordable housing for local workers.

Signs on vacant lot promise that condo buyers won’t need cars, thanks to nearby transit.

Photo credit: Storm Cunningham

The crumbling infrastructure and water shortages of this ancient, gargantuan city caught up with the developers, and got so bad in 2013 that the Mexico City’s Secretary of Urban Development, known in Spanish by the acronym Seduvi, halted all new building permits while they conducted a “technical study”.

Needless to say, that terrified local developers: few things are more worrisome than delays when one is working on borrowed money, and the interest in piling up. The moratorium also scared away potential condo buyers, who worried that the whole area might turn into a white elephant.The problem derived in large part from a lack of master planning, which was excacerbated by the large number of high-impact, non-integrated megaprojects, said Felipe de Jesús Gutiérrez, Mexico City’s director of urban development from 2006 to 2010. “The example that we should not follow is Nuevo Polanco,” he cautioned.

That said, anyone who visits Mexico City with enjoying the Museo Soumaya in particular, and Nuevo Polanco in general, will be missing a real treat.

See full Architectural Record article by Heather Corcoran.

See SOM site for Bancomer Operations Center.

See July 20, 2017 photo essay of Museo Soumaya by Laurian Ghinitoiu in ArchDaily.