When John Wick and his wife, Peggy Rathmann, bought their 540-acre ranch in Marin County, California, in 1998, So smitten were they with the wildlife, in fact, that they decided to return their ranch to a wilder state.

The first step they took toward what they imagined would be a more pristine state was to revoke the access enjoyed by the rancher whose cows wandered their property.

Within months of the herd’s departure, the landscape began to change. Brush encroached on meadow. Dried-out, uneaten grass hindered new growth. A mysterious disease struck their oak trees. The land seemed to be losing its vitality. “Our vision of wilderness was failing,” Wick told me recently. “Our naïve idea was not working out so well.”

Then Wick and Rathmann met a rangeland ecologist named Jeff Creque. Instead of fighting against what you dislike, Creque suggested, focus on cultivating what you want. Squeeze out weeds by fostering conditions that favor grasses. Creque, who spent 25 years as an organic-pear-and-apple farmer in Northern California before earning a Ph.D. in rangeland ecology, also recommended that they bring back the cows.

Grasslands and grazing animals, he pointed out, had evolved together. Unlike trees, grasses don’t shed their leaves at the end of the growing season; they depend on animals for defoliation and the recycling of nutrients. The manure and urine from grazing animals fuels healthy growth. If done right, Creque said, grazing could be restorative.

This view ran counter to a lot of conservationist thought, as well as a great deal of evidence. Grazing has been blamed for turning vast swaths of the world into deserts. But from Creque’s perspective, how you graze makes all the difference. If the ruminants move like wild buffalo, in dense herds, never staying in one place for too long, the land benefits from the momentary disturbance. If you simply let them loose and then round them up a few months later — often called the “Columbus method” — your land is more likely to end up hard-packed and barren.

The cows beat back the encroaching brush. Within weeks of their arrival, new and different kinds of grass began sprouting. Shallow-rooted annuals, which die once they’re chewed on, gave way to deep-rooted perennials, which can recover after moderate grazing. By summer’s end, the cows, which had arrived shaggy and wild-eyed after a winter spent near the sea, were fat with shiny coats.

When Wick returned the herd to its owner that fall, collectively it had gained about 50,000 pounds. Wick needed to take an extra trip with his trailer to cart the cows away. That struck him as remarkable. The land seemed richer than before, the grass lusher. Meadowlarks and other animals were more abundant. Where had that additional truckload of animal flesh come from?

Creque had an answer for him. The carbohydrates that fattened the cows had come from the atmosphere, by way of the grass they ate. Grasses, he liked to say, were like straws sipping carbon from the air, bringing it back to earth. Creque’s quiet observation stuck with Wick and Rathmann.

It clearly illustrated a concept that Creque had repeatedly tried to explain to them: Carbon, the building block of life, was constantly flowing from atmosphere to plants into animals and then back into the atmosphere. And it hinted at something that Wick and Rathmann had yet to consider: Plants could be deliberately used to pull carbon out of the sky.

This carbon-sequestering function is just the latest benefit uncovered in the rapidily-growing global trend known as “regenerative agriculture.”

The trend was first documented in Storm Cunningham‘s 2002 book, The Restoration Economy, which devoted any entire chapter to it. Back then, those few who knew anything about it referred to it as “restorative agriculture”, but “regenerative” has now been deemed a more all-encompassing term.

Regenerative farming and ranching has arrived in the nick of time, as poorly-managing cattle ranching has become a global crisis, even in places most people think of green paradises. For instance, on the other side of the planet from Marin County, California, yet another damning report has been issued on the deteriorating health of New Zealand’s environment.

In April of 2018, the New Zealand Ministry for the Environment released Our Land 2018, which reveals that the large-scale conversion and intensification of dairy farming is a key driver of environmental degradation.

“This report should be a serious wake-up call,” says Greenpeace sustainable agriculture campaigner, Gen Toop. “There are too many cows. We urgently need to diversify and transition away from intensive dairying.”

The report found that the “intensification of farming is increasing pressure on the environment”. It states: “Farming is considered to be intensifying when the amount of agricultural inputs going into the farm are increasing per hectare of land. Inputs include water, feed, agri-chemicals, and livestock numbers.”

The report also found that NZ is losing 192 million tonnes of soil a year into our waterways and into the ocean. 44% of this, 84 million tonnes, is coming from pastoral farming. “Healthy soil is the key to healthy rivers, healthy people and a healthy planet,” says Toop.”The industrial way are farming is literally squandering soil, which we ultimately depend on to grow food and sustain life.”

Other key finding include: 83% of our indigenous land vertebrates are threatened with extinction and rare wetlands and other rare indigenous ecosystems continue to be destroyed. “NZ is in a worsening freshwater crisis, our soils are degrading, our emissions increasing and we are continuing to lose our precious wetlands, native forests and tussock lands. 8 out of ten of our indigenous land vertebrates are now threatened with extinction. This Government must take urgent action to curb cow numbers and shift New Zealand agriculture away from destructive industrial practices and towards regenerative farming. Regenerative farming is the future for farming in NZ and it is already being practiced by innovative farmers around the country.”

Just recently, Patagonia released an international regenerative organic certification, although this has yet to be adopted in New Zealand. Here’s their definition of the solution: “Regenerative farming is a way of farming that treats a farm like a healthy ecosystem rather than a factory. It does away with environmentally damaging inputs and has been shown to be able to rebuild healthy soil, reduce pollution, sequester the carbon that causes climate change and protect biodiversity.”

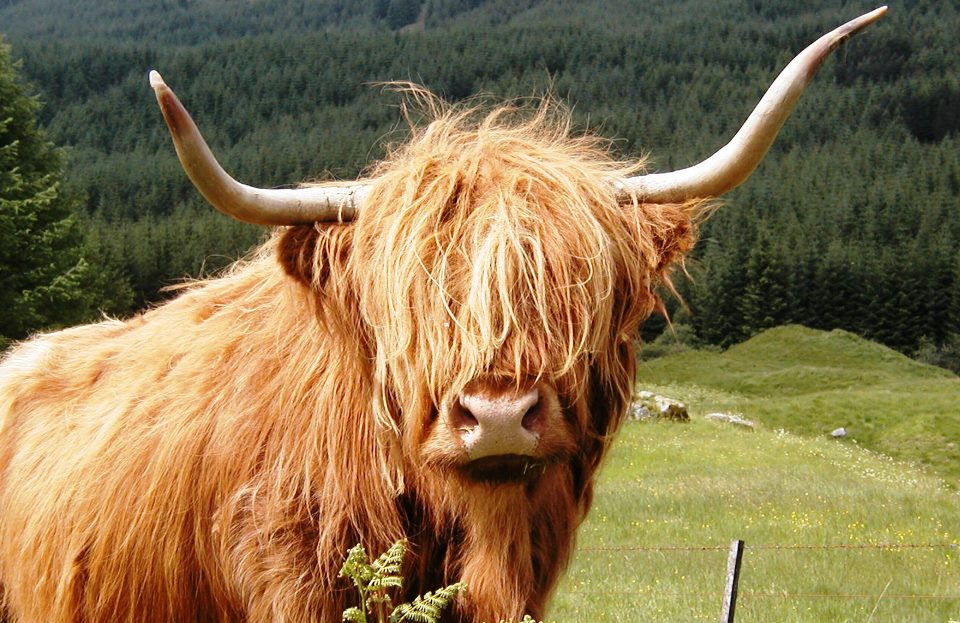

Highland cattle photo in the Glen Orchy area of Scotland by Storm Cunningham.

Read full New York Times article by Moises Valasquez-Manoff.