Rivers and streams have pulses, just as we (and everything else in nature) does. These pulses–which we call floods–are essential to scouring silt from streams in some spots, and depositing in others. This is how waterways evolve and adapt. But humans don’t like floods, so the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been bust for some two centuries, eliminating the living pulses of literally thousands of streams and rivers nationwide.

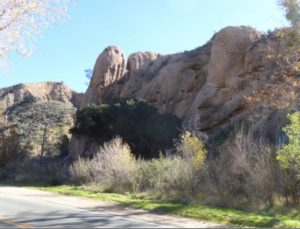

In northern Los Angeles County, California, county officials discovered that sections of Bouquet Canyon Creek had accumulated so much silt that the creek bed was level with the roadway, which caused dangerous overflows. As with most streams in urbanized areas, the flooding was unnaturally severe, due to the combination of large amounts of impervious surfaces (such as roads and parking lots), and due to lost wetlands (which act as sponges).

The initial response (as usual) was to dam the creek. But this destroyed critical habitat depletion for the endangered three spined stickleback. The stickleback is a minnow-sized fish that has managed to survive in the Santa Clarita Valley for an estimated 10,000 years. It only lives in four local creeks in the valley, one of them being Bouquet Creek.

As a result, a state bill was introduced that would allow the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works to “fast track” restoration of Bouquet Creek’s flows, and Governor Jerry Brown signed it into law on October 8, 2015. The primary purpose of this project is to restore habitat in Bouquet Canyon Creek. An important component of this restoration is reestablishing the creek’s flow pattern and flow-carrying capacity such that the now-dry reaches of the creek can again receive water.

Reestablishing creek flows to the southern end of Bouquet Canyon would potentially increase fish habitat and replenish the groundwater wells of residents downstream of the project site. The flow pattern reestablishment would also prevent flow impacts to Bouquet Canyon Road during reservoir releases and during many storm events.

five sites have now been restored along a 3-mile stretch of the creek. Shallower side slopes will be engineered next to the creek, riparian root mass material will be replanted along the side slopes, and boulder clusters will be placed at strategic points to slow creek flows and create eddying effects within the creek.

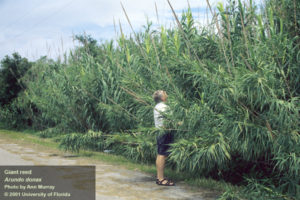

But that wasn’t Bouquet Creek’s only human-caused problem. An invasive giant reed (Arundo donax) was taking over the riparian areas of the entire watershed.

But that wasn’t Bouquet Creek’s only human-caused problem. An invasive giant reed (Arundo donax) was taking over the riparian areas of the entire watershed.

A recently-completed restoration project has now controlled the spread of 60 to 100 sites of Arundo donax within a 3.5 mile stretch of Bouquet Canyon creek, using integrated pest management. The sites were revegetated with native plant species endemic to the region (Baccharis salicifolia, Artemesia californica, and Quercus agrifolia) in order to enhance the natural ecology and restore biodiversity.

Photo of courtesy of the Puget Sound Aquarium.

See flow restoration project on Dept. of Public Works website.

See more about the native plant species restoration on Wetlands Recovery Project website.