The Caribbean King Crab might be the secret to wiping out a killer algae invasion on coral reefs, according to a new study by researchers at Florida International University (FIU).

Reefs provide many benefits to marine life and to people, yet climate change, pollution and an abundance of seaweeds are conspiring to snuff out reefs all over the world.

The algae invasion is particularly problematic because it smothers corals, reduces their growth and reproduction, and prevents establishment of juvenile corals. Seaweeds also fill in the nooks and crannies on coral reefs fish and other marine life use for shelter.

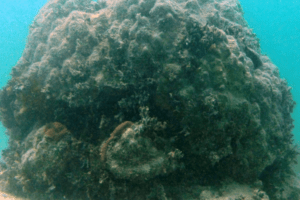

One of the patch reefs studied in the Florida Keys with patches of the calcareous green algae Halimeda.

In the Caribbean, the calcareous green algae Halimeda is taking over many reefs. Few animals tolerate its taste and texture. The Caribbean King Crab is the exception. So, researchers tested a few scenarios to see what would happen when concentrations of crabs were increased on reefs in the Florida Keys that were covered in Halimeda.

On reefs where people first scrubbed corals and introduced crabs, 80 percent of the algae was wiped out. On reefs where the crab didn’t receive clean up help from people, more than 50 percent of the algae was gone.

“Crabs are basically cleaning house so the corals can do better,” said FIU marine scientist Mark J. Butler, the study’s senior author.

Once the seaweed situation was under control, Butler and co-author Angelo Spadaro observed more fish and coral recruits on the reefs.

Butler is the Walter and Rosalie Goldberg Professor of Tropical Ecology in the FIU Institute of Environment and Department of Biological Sciences. He joined FIU in 2020 after 31 years at Old Dominion University, where, among other accolades, he was a recipient of the Virginia Outstanding Faculty Award, the highest honor for faculty at Virginia’s public and private colleges and universities.

For more than 30 years, the Florida Keys and Caribbean have served as the home base for his research and he has published more than 150 scientific articles on tropical marine ecology. He is continuing to explore how this latest work can become a large scale, viable solution for keeping corals healthy. He is particularly interested in using aquaculture techniques to rear Caribbean Kind Crab and deploy them to reefs when they are larger and less likely to be eaten by predators before they can get to work.

RESEARCH SUMMARY

Coral reefs are on a steep trajectory of decline, with natural recovery in many areas unlikely. Eutrophication, overfishing, climate change, and disease have fueled the supremacy of seaweeds on reefs, particularly in the Caribbean, where many reefs have undergone an ecological phase shift so that seaweeds now dominate previously coral-rich reefs.

Discovery of the powerful grazing capability of the Caribbean’s largest herbivorous crab (Maguimithrax spinosissimus) led us to test the effectiveness of their grazing on seaweed removal and coral reef recovery in two experiments conducted sequentially at separate locations 15 km apart in the Florida Keys.

In those experiments, we transplanted crabs onto several patch reefs, leaving others as controls (n = 24 reefs total; each 10−20 m2 in area) and then monitored benthic cover, coral recruitment, and fish community structure on each patch reef for a year.

We also compared the effectiveness of crab herbivory to scrubbing reefs by hand to remove algae. Crabs reduced the cover of seaweeds by 50%−80%, resulting in a commensurate 3−5-fold increase in coral recruitment and reef fish community abundance and diversity. Although laborious hand scrubbing of reefs also reduced algal cover, that effect was transitory unless maintained by the addition of herbivorous crabs.

With the persistence of Caribbean coral reefs in the balance, our findings demonstrate that large-scale restoration that includes enhancement of invertebrate herbivores can reverse the ecological phase shift on coral reefs away from seaweed dominance.

Unless otherwise credited, all photos are courtesy of FIU.