If you’re a long-term REVITALIZATION reader, you’ve seen countless examples of how the 3Re Strategy (repurpose, renew, reconnect) has been used to revitalize buildings, neighborhoods, communities and regions.

In this editorial, we’ll look at how it can be used to revitalize an organization, or a whole class of similar organizations. The example we’ll use is land banks.

While land banks were invented in the USA and are primarily found here, the lessons should be applicable to organizational leaders anywhere on the planet.

Land banks are a powerful, fairly-recently-created method of revitalizing cities suffering from depopulation, often combined with deindustrialization. In other words, communities with large inventories of vacant, tax-foreclosed properties.

That’s the theory, anyway. In actuality, far too many of them have devolved from a strategic revitalization entity to a tactical blight removal entity.

Applying the 3Re Strategy, land banks can be revitalized by:

- repurposing them from blight removal to revitalization;

- renewing them via the additional funding this higher-and/better mission should attract; and

- reconnecting them to the assets they are meant to renew via partnerships with other organizations whose mission contributes to revitalization, but who don’t have sufficient access to properties.

Those who are familiar with the strategic renewal process (AKA the “RECONOMICS Process”: see chart at right) know that the foundation of any revitalization program is the vision, and the strategy to achieve that vision.

The vast majority of land banks I’ve encountered have neither vision nor strategy. They just do real estate transactions; taking in vacant properties on one end and disposing of them (via sale, donation or demolition) on the other end.

In other words, rather than working consciously to achieve neighborhood revitalization, they merely remove what they perceive to be the problem, and hope that revitalization magically appears as a result. But hope is not a strategy.

I said “devolved” above, because the enabling legislation in some (maybe most) states originally envisioned the creation of local revitalization programs, not just blight removal mechanisms. In 2002, U.S. Congressman (D) from Michigan Dan Kildee sponsored the LAND BANK FAST TRACK ACT 258 of 2003.

The key text reads, “The legislature finds that there exists in this state a continuing need to strengthen and revitalize the economy of this state and local units of government in this state and that it is in the best interests of this state and local units of government in this state to assemble or dispose of public property, including tax reverted property, in a coordinated manner to foster the development of that property and to promote economic growth in this state and local units of government in this state. It is declared to be a valid public purpose for a land bank fast track authority created under this act to acquire, assemble, dispose of, and quiet title to property under this act.”

That makes it pretty clear that the legislators were focused on the ends, not just the means. But few organizational leaders are visionary or strategic: most are actually just managers. About 70 percent of the approximately 150 land banks that currently exist in the United States were created pursuant to comprehensive state-enabling statutes that authorize local governments throughout a state to create land banks.

According to the Center for Community Progress (CCP), the following eleven states have passed comprehensive state-enabling land bank legislation as of August 2015:

- Michigan (2004)

- Ohio (2009)

- New York (2011)

- Georgia (2012)

- Tennessee (2012)

- Missouri (2012)

- Pennsylvania (2012)

- Nebraska (2013)

- Alabama (2013)

- West Virginia (2014)

- Delaware (2015)

Founded in 2010, the Center for Community Progress is the only national nonprofit specifically dedicated to building a future in which vacant, abandoned, and deteriorated properties no longer exist. They serve as a sort of national association for land banks.

You’re probably wondering “If they’ve only been around since 2004, why do they need to be reinvented already?” Excellent question! I’m glad you asked.

Kalamazoo County Land Bank’s visionary Executive Director, Kelly Clarke at Prairie Gardens. This site of a former mental asylum got the 3Re Strategy treatment: repurposed as affordable housing, renewed with restored native prairie habitat, and reconnected to the community with new infrastructure.

As you can see in the enabling legislation above, land banks were meant to be community revitalization entities. But people and organizations tend to gravitate away from risk, and towards money. Most of the funding made available to land banks has been strictly for blight removal, which usually involves widespread demolition.

Demolition is relatively quick, simple, and risk-free. The opposite is true of community revitalization. It tends to be slow and complex, with uncertain outcomes (risk). Little wonder then, that so many of these community revitalization entities have devolved into little more than demolition agencies. Or, as Dave Allen, Executive Director of the Kent County Land Bank Authority in Grand Rapids, Michigan told me, they’ve become “a repository for everyone’s crap.”

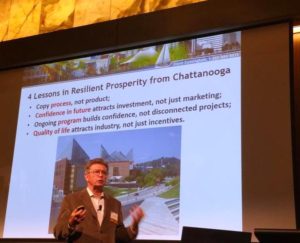

Back on October 2 and 3, 2017, I delivered both a keynote and a workshop at the annual conference of the Michigan Association of Land Banks in Battle Creek, Michigan. That was followed a day later by a workshop for the Kalamazoo County Land Bank.

The Battle Creek keynote focused on the latest trends in community revitalization strategies. The workshop on the following day focused on Land Bank 2.0: defining the next generation of land banks.

One of the attendees at that conference was David Allen. He understands that the simplest—not necessarily the easiest—way to harness a land bank’s physical assets to a vision and strategy is to partner with (or at least collaborate with) other organizations that have a vision and strategy, but lack physical assets.

Here’s how he described the benefits of such an approach, in an email to me prior to the conference: “The Grand Rapids Community Foundation (GRCF) has a major initiative called Challenge Scholars It is a multi-million dollar investment on behalf of the GRCF. However, once launched a very negative unexpected consequence occurred. Property values and rents in the Challenge Scholar neighborhood immediately soared! Soon the very families they made a multi-million investment to help were being priced out of the neighborhood. The GRCF and the KCLBA partnered together to assemble multiple parcels literally adjacent to the Challenge Scholar middle school, Harrison Park. The KCLBA brought in a well established non-profit housing developer and a rather significant LIHTC project is about to break ground on this site. The GRCF PRI was used to purchase the key piece of property in this development. This only happened because the KCLBA was in regular communication with the GRCF.”

Allen takes a similarly-collaborative approach to working with the for-profit sector, as well. Here’s how he described his land bank’s mission and approach to me: “KCLBA provides tools to local units of government—as well as nonprofit and for-profit developers—to revitalize and stabilize communities throughout Kent County. By purchasing and facilitating acquisition and rehabilitation of bank-owned and tax-foreclosed properties, the KCLBA helps:

- Kent County’s local units of government:

- stabilize neighborhoods;

- eliminate blight;

- increase property values;

- create economic development opportunities; and

- preserve neighborhood character.

- Nonprofit developers:

- revitalize properties by giving them…

- access to tax- and bank-foreclosed properties in their development areas.

- For-profit developers:

- quickly clear title on properties;

- obtain brownfield designation on contaminated properties;

- fully inspect and make an educated decision on purchasing tax-foreclosed properties; and

- provide access to purchase bank foreclosed properties.“

There are three key reasons that outcomes from community revitalization efforts are so uncertain:

- They don’t clearly define what they mean by “revitalization”, so their vision is unclear;

- Vision drives strategy, which is the second problem: most community leaders don’t understand what a strategy is, of how to create an effective one;

- Vision and strategy are just two elements of the overall renewal process, which also includes partners, policies, projects, and programs. Nothing in nature or the world of humans is produced without a process.

Most communities lack a clear vision, an effective strategy, and a comprehensive renewal process. Little wonder then that they also lack revitalization. (You can learn more about all three here.)

Of course, not all land banks see themselves only as blight removal agencies.

Of course, not all land banks see themselves only as blight removal agencies.

The Kalamazoo (Michigan) County Land Bank, for instance, is on the leading edge of community revitalization.

They’ve adopted the 3Re Strategy (repurpose, renew, reconnect) not just as a tool, but as their slogan, as seen here on the cover of their 2016 annual report.

Here’s the article that appeared in REVITALIZATION back in 2015 that originally drew my attention to them, leading to my work for the Michigan Association of Land Banks.

Here are two paragraphs from a recent Next City article about the Philadelphia Land Bank:

“The land bank has a five-year goal of reactivating roughly 2,000 properties. So far, according to the city, the number of properties sold through the program is 196, and most were vacant lots. Any streamlining Rodriguez does will have to cover mastering the agency’s elaborate acquisition policies. As outlined in the strategic plan, released in February, the criteria for whether or not the land bank can transfer certain parcels depends on the intended re-use. The re-use category also determines the approval process and which city offices and organizations have to weigh in.”

“The ability to be strategic is key, says Frank Alexander, co-founder of Center for Community Progress, a national nonprofit that focuses on vacant properties. While Philly’s five-year targets forecast that the land bank will add 7,727 publicly owned parcels to its holdings, it will also acquire another 1,650 tax-delinquent properties. The agency also has outlined a mix of types of properties for its disposition process. Sixty-five percent of land returned for active use will be for housing, and in an effort to ensure affordability, only 25 percent of that won’t be restricted by income brackets.”

Kalamazoo County Land Bank’s office is on this revitalized old commercial property. Shown here is a bioswale of native plants. Using the 3Re Strategy, the property was repurposed and renewed, and was reconnected to the community via a river trail.

As the Kalamazoo County Land Bank’s projects reveal, the process of becoming more beneficial to their community isn’t just about repurposing, renewing and reconnecting. They also looked at scale, and realized that focusing on individual residential properties was far too limiting: as the Prairie Gardens example (above) shows, they are creating entire new neighborhoods out of blight.

And it’s not just about increasing the physical scope: extending the chronological scope is key, too. They aren’t just taking in houses and disposing of them as quickly as possible: Prairie Gardens also shows that they are into their properties for the long haul. For a land bank that truly understands how to revitalize a place, holding on to properties while they revitalize the entire neighborhood offers a major new revenue stream. Everyone wants to invest in a neighborhood that’s coming back to life, which means the land bank would enjoy actual appreciation of assets that most people see as liabilities.

Some day, I hope to see an app invented that allows entities like land banks to quickly and easily create a “mini-TIF” (tax increment financing), which would provide the financial resources to do renewal on a grander scale, including brownfields cleanup and infrastructure renewal.

Getting back to vision and mission: Maybe the best strategic partnership for a huge land bank like Philadelphia’s would be with Community Land Trusts (CLT), which have the mission of providing permanently affordable housing, usually in neighborhoods and communities that are revitalizing.

Rather than explain the advantages of this approach here in this editorial, here’s an excellent article on the subject. The fit is natural: CLTs have a public benefit vision and strategy but need residential property. Land trusts have tons of residential property, but are (usually) weak on vision and strategy.

If you’d like to read more about the revitalizing activities of land banks, here are some article that have appeared in REVITALIZATION over the years:

- https://revitalization.org/article/new-study-reveals-the-revitalizing-economic-impact-of-land-banks-in-michigan

- https://revitalization.org/article/how-should-the-next-generation-of-land-banks-evolve-to-better-redevelop-brownfields

- https://revitalization.org/article/the-growing-trend-towards-revitalizing-foreclosed-properties-via-community-land-banks

- https://revitalization.org/article/does-brownfields-revitalization-define-the-4th-generation-of-land-banks

- https://revitalization.org/article/oregon-progress-on-creating-urban-land-banks-to-clean-up-brownfields

Lastly, here are a couple of articles about Community Land Trusts, in case you need to get up to speed on that growing trend:

- https://revitalization.org/article/community-land-trust-hopes-minimize-gentrification-dc-neighborhood-revitalizes

- https://revitalization.org/article/community-land-trusts-restore-affordable-housing-revitalize-neighborhoods

So, the best way to revitalize an organization that supposed to be revitalizing your community? The same way it should be revitalizing your community: via the 3Re Strategy: 1) find a viable new (or enhanced) purpose for the organization; 2) this will attract the funding and other resources needed to renew it; 3) then reconnect it to the community via effective partnerships.

Ideally, you organization would foster a comprehensive local renewal process, comprising 1) a regenerative vision and a regenerative strategy, 2) supported and implemented via regenerative policies, regenerative partnerships and regenerative projects, and 3) perpetuated by an ongoing program designed to produce resilient prosperity for all.

About the Author:

Storm Cunningham publishes REVITALIZATION.

Storm Cunningham publishes REVITALIZATION.

A former Green Beret SCUBA Medic, Storm lives in Arlington, Virginia, and is the author of two highly-acclaimed books: The Restoration Economy (Berrett-Koehler, 2002), and Rewealth (McGraw-Hill Professional, 2008). His upcoming 3rd book is RECONOMICS (coming January 2020).

His 100+ global client list includes: US State Department, Boeing, Harvard University, Ontario Chamber of Commerce, Israel Planners Association, European Property Italian Conference, University of Guadalajara, National Arbor Day Foundation, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, American Institute of Architects, Project Management Institute, US Embassy (Poland), Governor of Montana, Canadian Urban Institute, Santee Cooper, Urban Land Institute, University of Texas, Leadership Cleveland, and many more.

Learn more about his consulting, books, talks, and workshops at StormCunningham.com [Image: Storm keynoting conference of the Planning Institute of Australia (2015). Photo by Adam Beck.]

See article by Cassie Owens in Next City.