Puerto Rico (Spanish for “Rich Port”) is officially named the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. “Free Associated State of Puerto Rico”)[b] and briefly called Porto Rico,[c][15][16][17] is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the .

This archipelago northeastern Caribbean Sea includes the main island of Puerto Rico and a number of smaller ones such as Mona, Culebra, and Vieques (long used as a training area by the U.S. Navy to practice bomb runs). The capital and most populous city is San Juan.

The official languages are Spanish and English, though Spanish predominates, and it has a population of about 3.4 million. The island’s rich history, tropical climate, diverse natural scenery, renowned traditional cuisine, and attractive tax incentives have long made it a popular destination for travelers from around the world.

But now, after a decade of economic depression and encouragements by financial institutions to paper over their problems by borrowing, Puerto Rico carries $72 billion in “unpayable” debt. The local government has made plenty of mistakes that exacerbate the crisis, but U.S. Congress played a major role too. For instance, they made shipping costs to the island larger, and Medicare reimbursements smaller, along with many other rule changes that increased economic hardship. Unemployment on the island has now hit 12 percent, and more Puerto Ricans have migrated away in the last two years than in all of the 1980s and 1990s combined.

The situation has attracted no shortage of vultures who want to profit from the crisis, as well as people who want to help. For instance, on October 13, 2016, the Association of Financial Guaranty Insurers (AFGI) Puerto Rico Revitalization Conference took place in New York City. [AFGI is the trade association of financial guaranty insurers and reinsurers of municipal bonds and other types of public and private debt. AFGI members, also known as bond insurers or monoline bond insurers, guarantee the timely payment of principal and interest as due on insured securities in the event of a payment default by the issuer. Financial guaranty insurance is designed to improve local governments’ access to capital markets by protecting investors from the risk of nonpayment.]

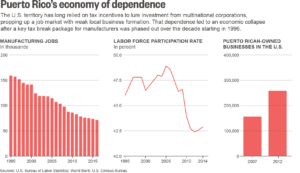

In 1976, Congress passed Section 936 of the federal tax code, granting U.S. corporations a tax exemption from income originating from U.S. territories. Manufacturers, largely from the pharmaceutical industry, flocked to Puerto Rico to take advantage of these tax breaks.

It was boom time on the island; until the tax incentives phased out in 2006 (Congress voted in 1996 to rescind them), the island enjoyed 28 out of 29 years of economic growth. Since 2005, Puerto Rico has seen negative growth eight out of 10 years and, just as the automotive industry left Michigan, so too fled Puerto Rico’s most prevalent manufacturers — pharmaceutical companies — in droves.

To make matters worse, the island’s agricultural industry is at a standstill, importing more than 85 percent of its produce. Puerto Ricans also pay two to three times more for electricity than average Americans, due in part to their dependence on oil imports and because the government-owned utility company is plagued with billions in debt.

On June 30, President Barack Obama signed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), which creates a committee (consisting of no elected Puerto Rican officials) to oversee the island’s finances. Some have criticized the law as a devolution to America’s colonial past.

One catalyst to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan was the role of the city’s emergency financial manager, empowered by the state of Michigan to dictate practically every aspect of local governance. The financial manager wasn’t accountable to Flint residents, and didn’t have to worry about whether ignoring their concerns about lead-tainted water would harm future election prospects. Democracy in Flint, for all practical purposes, had been suspended by the state.

Now we’ve exported this model to Puerto Rico. PROMESA imposes a federal oversight board that effectively turns the commonwealth into a colony. Many expect even further disaster for vulnerable Puerto Rican citizens, partly from the corporate bonanza PROMESA creates via privatization of public functions.

One solution to the mess would be for Puerto Rico to file bankruptcy and restructure its debt. But peculiar rules disallow commonwealths from utilizing U.S. bankruptcy laws the way cities like Detroit have. These rules give so-called “vulture funds,” who have scooped up the Puerto Rican debt at a discount, the opportunity to demand repayment in full amid threats of a lawsuit. The vultures have little incentive to make a fair deal, because the laws work so completely in their favor.

Puerto Rico is now trying to bring back productive corporations through a series of tax incentives. Two laws in particular, Act 73 (2008) and Act 20 (2012), set a fixed income tax rate of 4 percent for commercial manufacturers and companies exporting services from the island, respectively. A 50 percent tax credit for research and development activity costs has also been instituted under Act 73. According to Puerto Rico Secretary of Economic Development and Commerce, Alberto Bacó Bagué, “20% of the companies that operate under [Act 20] are tech oriented … and the rest have a tech-related component.”

“Technology is certainly one of the pillars of our economic development program,” says Bacó. “As of today, we have a strong tech cluster with examples like Infosys, a global leader in creating breakthrough solutions that address mobility, sustainability, big data, and cloud computing and Honeywell, with a new EMI (electronic magnetic [sic] interference) research lab that alone will create 300 jobs.”

To buoy the tech sector, Puerto Rico is trying to reinvent itself as a knowledge-based economy that will compete globally in part by creating a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem. But economists are increasingly realizing that tax incentives–the standard economic development tool of cities and regions for decades–seldom create sustained revitalization on their own.

In fact, the over-use of tax incentives by economic developers often leads to devitalization. General revenues dry up because companies are paying no taxes, thus degrading public services and quality of life. And the low-quality, low-wage employers such incentives often attract tend to leave town as soon as the freebies expire. Further devitalization ensues, since high-quality employers are primarily attracted by high quality of life and efficient infrastructure.

In fact, the over-use of tax incentives by economic developers often leads to devitalization. General revenues dry up because companies are paying no taxes, thus degrading public services and quality of life. And the low-quality, low-wage employers such incentives often attract tend to leave town as soon as the freebies expire. Further devitalization ensues, since high-quality employers are primarily attracted by high quality of life and efficient infrastructure.

For decades, the island bet on multinational manufacturers, who bailed when the U.S. repealed the tax incentives. Meanwhile, frustrated local entrepreneurs–who got no such support from their government–fled to the mainland. “We didn’t have the foresight of developing local industry,” says horse breeder Prudo Jimenez. “We depended always on people from the outside.”

Many Puerto Ricans fear that more tax break schemes will only promote the same artificial stability that preceded the latest economic crash. The island needs to evolve from “a culture of employees to a culture of entrepreneurs,” said Antonio Medina, who stepped down in August as the chief of Puerto Rico’s economic development agency, known as PRIDCO.

More promising is the strategy of breeding home-grown businesses. For instance, the Puerto Rico Science, Technology and Research Trust envisions turning the island into a regional tech hub by 2020, The trust recently established the Technology Transfer and Commercialization Office to help develop and commercialize intellectual property from the island’s universities, and to provide income tax breaks for researchers working in their grant program.

Trust CEO Lucy Bacó says, “While big hitters are important, a new breed of entrepreneurs has flourished, and we have joined forces with our diaspora using their knowledge and network reach to further propel economic growth.”

Parallel18, a startup accelerator in San Juan backed by the trust and the government, has reached out beyond the Puerto Rican diaspora, soliciting help from Start-Up Chile founder Sebastian Vidal.

Tourism, is another obvious economic sector with much untapped potential. “The embryo of the new Puerto Rico is growing robustly,” says Jon Borschow, founder of the nonprofit Foundation for Puerto Rico, which focuses on building the island’s lagging tourism industry. including ecotourism. “It’s just not visible, because it hasn’t broken through the shell of the old Puerto Rico.” The foundation’s stated mission is “to transform Puerto Rico into a destination for the world by driving economic and social development through sustainable strategies“.

Renewable energy is crucial to revitalization, as well. Four-fifths of Puerto Rico’s power comes from petroleum, which the island neither produces nor refines. “Sustainable energy is key to Puerto Rico’s future,” says Puerto Rico journalist Juan González. In September of 2016, Puerto Rico activated the largest solar farm in the Caribbean on northwest coast.

The ultimate revitalization solution will, of course, only come about when today’s reactive, crisis-response mode is abandones in favor of an effective long-term strategy and comprehensive renewal process. This would help inspire real confidence in the future of Puerto Rico’s economy, which is the single most important key to revitalization. Only with such confidence will residents, investors, and businesses remain on the island. And only with that confidence will new residents, investors, and businesses be attracted to the island.

The ultimate revitalization solution will, of course, only come about when today’s reactive, crisis-response mode is abandones in favor of an effective long-term strategy and comprehensive renewal process. This would help inspire real confidence in the future of Puerto Rico’s economy, which is the single most important key to revitalization. Only with such confidence will residents, investors, and businesses remain on the island. And only with that confidence will new residents, investors, and businesses be attracted to the island.

Most places have some elements of a renewal process. But with missing steps, their efforts tend to be unproductive or less-productive. Here are the seven crucial elements of a complete process:

- Visions adaptively guide actions to the desired outcomes;

- Strategies drive actions to success;

- Partners fund or support actions;

- Policies enable strategic actions;

- Plans organize actions;

- Projects are actions;

- Programs perpetuate, evaluate, and adjust actions. Ongoing programs create synergies, capture momentum (to grease the wheels for more projects), and inspire confidence in the local future.

In cities, regions, and countries around the world the two most common gaps in the regeneration process are almost always “strategy” and “ongoing program”. While there are some good strategies being implemented by non-profit groups, as we’ve seen above, they seem to be missing both in Puerto Rico’s government, and in the “assistance” being provided by the United States.

Photo of San Juan, Puerto Rico’s Old City Wall via Adobe Stock.

See full TechCrunch article by Jim Glade.

See full Reuters article by Nick Brown.