The Bintang Bolong is the largest, most water-rich river in West Africa, serving both Senegal and The Gambia.

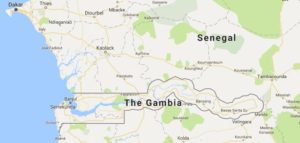

The Gambia (officially the Republic of The Gambia), is the smallest country in mainland Africa, and certainly the most strangely-shaped.

It’s entirely surrounded by Senegal, except for its coastline on the Atlantic Ocean at its western end.

As you can see from the map, a major portion of that coastline in composed of the estuary formed by the Bintang Bolong River.

In August of 2017, the Gambia Department of Parks and Wildlife, collaborating with Sahel Wetland and three local communities, spent two days planting mangrove trees around the Bintang Bolong estuary.

Kawsu Jammeh of Parks and Wildlife said that the primary purpose was restore biodiversity, such as wading water birds, mud crabs, reptiles, butterflies, insects, mammals and other wildlife that has suffered from widespread destruction of mangrove forests.

Another goal is to revitalize the economy by restoring fisheries and and boosting ecotourism. “We do not have to wait until the forest disappears completely,” he said, adding that they must restore the wetland in order to support the well-being of future generations.

This restorative wetland work in Gambia comes at a time of increasing distress over the general loss of wetlands in that section of Africa.

On May 3, 2017 Wetlands International published a report aimed at highlighting to policymakers the relationship between the health of wetland ecosystems and involuntary human migration in the Sahel region of Africa.

Entitled “Water Shocks: Wetlands and Human Migration in the Sahel” the publication examines how poor water management leads to degradation of ecosystems, and is an overlooked cause of human migration, including to Europe.

Human displacement is a common situation in the Sahel region. For instance, around Lake Chad, the Boko Haram insurgency has displaced more than 2.3 million people since mid-2013, including 1.3 million children. The Lake Chad Basin has lost 95% of its surface area due to water abstraction for irrigation projects, and youths from this region are joining armed groups because of lack of opportunities.

“Humanitarian organisations need to connect their work with the environmental and development actors to find durable solutions. We need to understand better the complex and multifaceted drivers of involuntary migration, social conflict and poverty, which may be rooted in the depletion of natural resources,” concluded Juriaan Lahr, Head of International Assistance of the Netherlands Red Cross Society.

According to the UN, there are 20 million people in the Sahel who are food-insecure, mainly due to lack of water. If development plans for future hydropower and irrigation projects do not position ecosystems at the heart of national and regional development strategies, Europe and other nations will fail to achieve their goals for inclusive sustainable development and increased resilience to climate change.

The European Union has a five-year 80 million euros funding package available to support disaster risk management across Sub-Saharan Africa[1]. By 2020 the European Union and the African continent aims to increase both energy efficiency and the use of renewables by building 10,000MW of new hydropower facilities. These investments must assess the economic and social costs of environmental degradation.

“Driving forward inclusive and sustainable development in the Sahel is an urgent, global priority. But this will only be achieved by shifting from the traditional development paradigms and hard infrastructure schemes which play havoc with the natural hydrology of the region. Maintaining and restoring the natural resource base is essential to increase water and food productivity and provide livelihood strategies to cope with a changing climate. In this context, wetlands such as river floodplains and lakes are disproportionately important; especially to the most marginalised and poor people of the region,” said Jane Madgwick, CEO of Wetlands International.

The drying out and siltation of the Senegal River’s large coastal delta due to the Manantali Dam has resulted in the loss of 90 per cent of its fisheries.

The Maga Dam and a water diversion scheme on Cameroon’s Logone River floodplain damaged downstream flood-recession agriculture, pastures, fisheries and wildlife tourism. These changes annually cost 2.5 million euros against the 10.7 million euros a year that the annual flooding contributed to the local economy.

The planned Fomi Dam in Guinea could cut fish catches in the delta by 31 per cent and reduce the pastures by 28 per cent.

Dams in northern Nigeria have reduced the Hadejia-Nguru wetland. The benefits of the floodplain ranged from approximately US$9,600 to US$14,500/m3 of water, compared with US$26 to US$40/m3 for the irrigation project.

Featured photo of the Bintang Bolong by Atamari via Wikipedia.