It wasn’t long ago that now-vibrant downtown Los Angeles felt quiet on evenings and weekends. Once the bankers and lawyers and office managers went home, you could walk for blocks without finding somewhere to have a cup of coffee. Dinner options were scant, and safety on the dark, empty streets at night was a concern.

But over the past decade or two, things have changed: Developers have transformed Beaux-Arts banks, Art Deco office buildings, and early 20th-century theaters and warehouses into loft apartments, restaurants, galleries, and clothing shops. Grocery stores and dog parks soon followed. Now, the streets of downtown L.A. bustle long after 5 p.m.

Similar changes are happening all across the country. According to the 2010 census, more than 80 percent of Americans now live in urban areas—and that number is only growing. Where most people once aspired to live in suburban houses with a yard and a garage, a new generation is embracing the diversity, historic character, and less car-centric lifestyle that a city provides. Baby boomers, drawn to those same qualities, are following. Yes, cities are having a big moment—and that’s creating a huge opportunity for the preservation community.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation has been working for decades on initiatives designed not only to keep the historic fabric of cities intact, but also to improve the lives of urban residents. Its Main Street America program, relaunched as an independent subsidiary in 2013, has helped revitalize thousands of downtowns and commercial corridors over the past 36 years, and since 2000 the National Trust Community Investment Corporation (NTCIC) has placed the National Trust at the table with developers and business owners to identify financing that helps old buildings serve their communities again.

More recently, the National Trust established the Preservation Green Lab to promote more sustainable cities, neighborhoods, and communities through the reuse and retrofitting of old buildings.

“We want preservation to become the default for cities,” says National Trust president Stephanie K. Meeks. “We want cities to understand that historic buildings are a resource, and to have their first response always be to figure out how to restore and reuse them and keep them in active service for their community.”

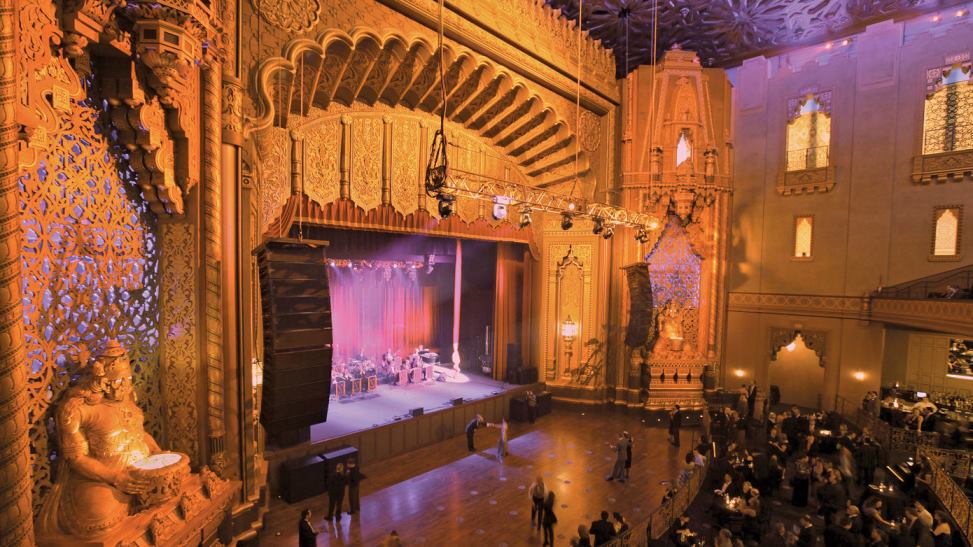

In 1997, developer and Oakland, California native Phil Tagami proposed renovating the long-vacant Fox Theater (pictured above). Those plans finally moved forward in 2004, and around the time they were announced, something interesting happened: Restaurants began opening nearby. New businesses moved in. Quiet Uptown began to bustle.

Photo credit: Jennifer Reiley, ELS Architecture and Urban Design