Interest in discovering and restoring urban ecology is exploding. A livable city is both vibrant green and vivid blue. Environmental organizations are tripping over themselves to develop urban initiatives and establish a stronghold in formally forgotten places to meet the interests of energized urban dwellers.

One of the best places to concentrate nature programming and improve ecological integrity in the urban biosphere is in and along rivers.

Urban river revitalization is not new. Often cited as urban river restoration exemplars, San Antonio, Texas and Providence, Rhode Island have shown that if you uncover your river and turn towards it, great things can happen along the water.

However, in both examples ecological values played a secondary role to community interests. What happens in the water matters too. Rivers are undisputed aesthetic amenities, but if seen as only shimmering window dressing, and not urban wilds with essential functions and values, simply turning towards them is not enough.

Presently there is no place in North America where engineers, academics, landscape architects and restoration planners can test, monitor and evaluate urban river restoration techniques. A proving ground does not exist where researchers and practitioners can experiment with urban river restoration techniques and see how interventions can revive ecological integrity as well as revitalize the surrounding neighborhoods. There is no innovation space where advocates from cities struggling to revive their waterfronts can learn, understand and implement in real time.

In Western Massachusetts, situated snugly in the Hoosic River Valley, is the small mill city of North Adams. At the turn of the last century North Adams was home to 24,000, today it is the smallest city in the state with only 14,000 residents.

In Western Massachusetts, situated snugly in the Hoosic River Valley, is the small mill city of North Adams. At the turn of the last century North Adams was home to 24,000, today it is the smallest city in the state with only 14,000 residents.

The story of North Adams’ decline has been replayed a thousand times in North America; manufacturing all but disappeared in the 1980s, and as mills were shuttered, workers left and immigration petered out. North Adams has an adult poverty rate of 17% and 25% of children live at or below the poverty line.

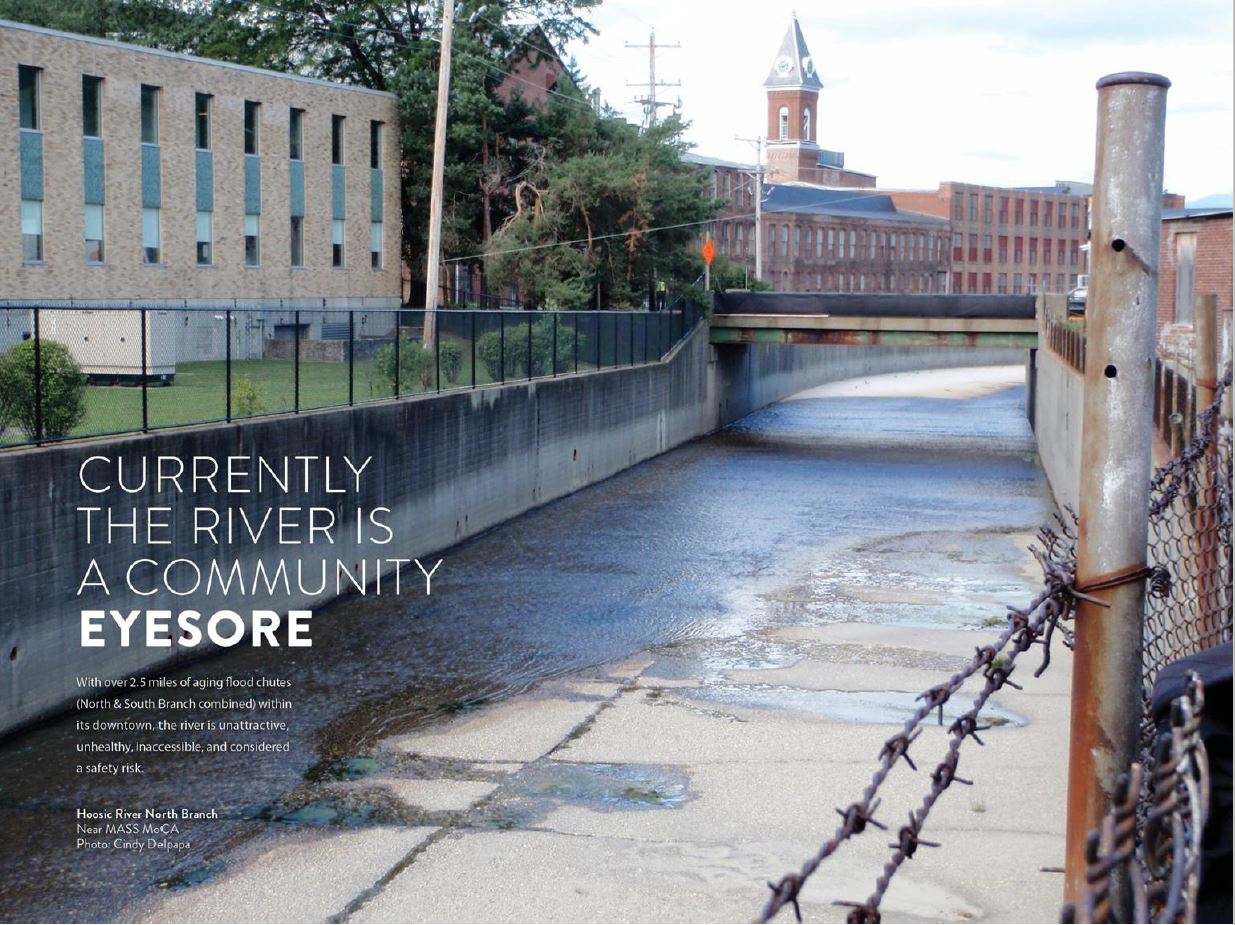

Despite its diminutive size, North Adams has big city river issues. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, after epic floods in the 1930s and 1940s, erected an almost three-mile long, three-sided concrete box and conveniently placed the river inside the functional equivalent of a sarcophagus. Ninety degree vertical banks, 20-feet deep, are grimly adorned with chain link. Trapped inside, the Hoosic River boils in the sun and supports little to no aquatic life. Riparian vegetation cannot take root and habitat-rich woody debris is unceremoniously swept away.

While floods are contained, the Hoosic River in North Adams is inaccessible, immobile, and lifeless. Healthy rivers need to access their floodplains, swaths of streamside vegetation are essential to filter pollutants, and habitat complexity (pools, riffles and runs) is a necessary to support fish and wildlife.

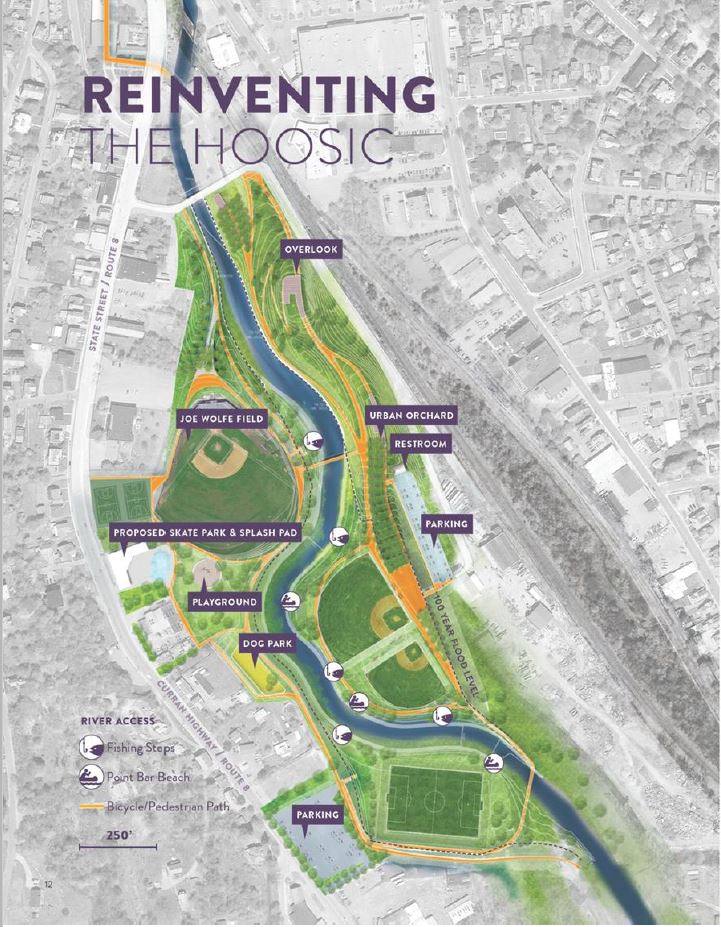

Grassroots organizations, led by the Hoosic River Revival, are rallying around the revitalization of the river and plans to transform the riverway are underway. As part of the planning process, the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration commissioned HR&A Advisors, economic development consultants, to look at the need for an urban river innovation center, and whether such an innovation space could be developed in tandem with the on-the-ground improvements in North Adams. Finally, HR&A examined what it would take to establish a full-fledged urban river laboratory.

In a series of interviews with urban river experts across the country, HR&A staff found that there is a distinct need for such a center and that restoration professionals and advocates could greatly benefit from one.

In a series of interviews with urban river experts across the country, HR&A staff found that there is a distinct need for such a center and that restoration professionals and advocates could greatly benefit from one.

Although there are sterling examples of urban river restoration, there is no clearinghouse and/or experimental space to test the viability and effectiveness of restoration/ revitalization techniques.

Examples of these techniques include: storm water best management practices, habitat structures, flood-friendly parks, flexible natural buffers, bank treatments, floodplain connections, and erosion controls. In addition, the socio-economic benefits of restored urban rivers could be measured and analyzed.

North Adams could support a new innovation center if the restoration community is galvanized around the concept; or perhaps it could be built in your city.

While North Adams will eventually serve as a model urban river restoration and revitalization, without a dynamic feedback loop, lessons learned cannot be told and the progress of urban river restoration will be limited.

Images courtesy of Hoosic River Revival, Sasaski Associates, and Inter-Fluve.

About the Author:

Tim Purinton is Director of the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration in the Department of Fish and Game.

Tim Purinton is Director of the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration in the Department of Fish and Game.

Tim was a former Governor Robert F. Bradford Fellow for Excellence in Public Administration at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

For a copy of the HR&A report, contact him at tim.purinton@state.ma.us.