This Guest Article for REVITALIZATION is by Eliza Charley of CoDesign Studio.

Rapid revitalization as a response to rapid urbanisation: unlocking social capital in existing communities to transform their neighbourhoods for long-term systemic change.

It is estimated that 30% of public land is underutilised [The Economist 2015]. With rapid urbanisation and rampant social isolation set to increase to epidemic levels, it is more important than ever that we find tested, scalable methods to breathe new life into spaces and transform them into places for our communities to thrive.

Imagine these three spaces: a community physically divided by an abandoned 1890’s sewerage pipeline; a traffic-heavy square with no place for lonely youth to connect; and a down-at-the-heels beachside mainstreet with growing vacancies losing its financial viability.

What could these very different urban landscapes possibly have in common? Thanks to a locally-led placemaking program in Australia called The Neighbourhood Project, all three have now been transformed into thriving, greener, and more vibrant places for communities.

Locals at work in Edithvale Collective’s local place greening, community engagement, and vibrancy activation, part of The Neighbourhood Project by CoDesign Studio in 2018.

The Neighbourhood Project is a three-year action research project run by CoDesign Studio in the city of Melbourne from 2015-2018. The program aimed to catalyse long-term council process change in order to unlock long-term community benefits.

It was hypothesized that creating an enabling environment at a local government level, with less red tape, would allow community members to have greater say and ability to take action in how their places are shaped and formed. What resulted was in fact far more interesting.

Three iterations of the project revealed that addressing community capacity-building first, alongside creating an enabling environment at a governance level, was actually the key to unlocking long-term self-sustaining outcomes for people, process, and place.

Rapid urbanisation requires a rapid revitalization

Rapid urbanisation is occurring globally. According to the UN’s 2015 report World Population Prospects, planet Earth will be home to nine billion people by 2050, and two-thirds of them will be living in cities. In fact, according to a report by the World Economic Forum in 2016, urban areas around the world are already receiving an influx of 200,000 new inhabitants every day.

Australia itself is feeling the impact of this rapid urbanisation, with higher density living on the rise alongside rampant social isolation. Loneliness in Australia is expected to hit epidemic levels by 2025, which is particularly concerning when one considers that loneliness puts us at a similar risk of death as smoking or heart disease (Harvard Medical School 2016).

Let’s Make A Park youth-led group from Strathmore making a difference in Melbourne’s concrete-heavy northern suburbs in 2018.

Place is known to be one of the top determinants of health. According to the World Health Organization, our social, economic, and physical environment have a direct impact on our health. In fact, the WHO reports that 3.3% of deaths globally can be directly linked to a person’s access to public space, especially green space.

The nature of public process can make it difficult for governments and communities to respond quickly to the place needs of ever-growing populations. Traditional methods of citymaking are not responsive enough to adapt quickly, and the top-down approach of place designers is inherently primed to remove existing communities from having a say in the process of how their places are built, shaped and managed.

Grassroots movements such as tactical urbanism have emerged to empower change from a community-level, taking an “act now, ask permission later” mentality, with some positive results. However, government authority and red tape can prevent these interventions from having long-term change, and the global urbanisation trend demands a long lasting response.

Activate existing spaces by unlocking People, Process and Place

Place matters because people matter. Places determine our health, wealth, and happiness. Since its founding in 2012, CoDesign Studio has been tackling the issue of urbanisation through revitalisation of existing and underutilised ‘spaces’, turning them into ‘places’.

Today, we are a placemaking thought-leader and strategic advisory outfit with the motto “Prosperous places; better lives,” built on a foundation of evidence-based research.

In researching a methodology on how to catalyse multi-stakeholder collaboration to achieve lasting change to a place, CoDesign Studio also unlocked a way to deliver positive development for people and the processes connected to that place.

In researching a methodology on how to catalyse multi-stakeholder collaboration to achieve lasting change to a place, CoDesign Studio also unlocked a way to deliver positive development for people and the processes connected to that place.

People, Process, and Place, are now the three drivers of change that CoDesign Studio touts to be best-practice for measuring and implementing social change with regards to place.

This way locally-led projects have been shown to deliver more than physical outcomes, to provide a quadruple bottom-line of placemaking: social, cultural, environmental and financial place value.

The chicken, the egg, and pop-up

When local governments create a pathway for communities to more easily take action at a local level, this understandably allows for more pop-ups, trials, and temporary actions to take place. These in turn serve as prototypes for gauging community buy in, community ownership, as well as initial social and physical impact on the place, which feeds back as information for council to sure up further, more substantial changes to place.

Concurrently, when local community members take temporary action, this action in and of itself serves as a low-cost means of identifying roadblocks and red tape at a council level. In turn, this highlights pathways and permitting procedure which may require review in order to create an enabling environment.

Williams Landing Community Garden, created atop a decommissioned 1890’s heritage-listed pipeline, and now adopted into the region’s linear park plan.

So, which comes first? Top-down council change or bottom-up community action? The ideal answer is both: top down and bottom up at the same time through a collaborative approach to locally-led placemaking.

To this end, The Neighbourhood Project tested three variations of a program across eight Australian councils, and nine projects, to research how to best deliver small-scale interventions and place activations as a means of prototyping ideas, garnering council support, building community capacity for leadership, and ultimately be a feasible catalyst for long-term change.

Essentially, the project tested a roadmap and capacity-building program at both a council level and a community level to leverage the humble pop-up as a catalyst for connecting councils and community members for place change.

Three case studies on locally-led revitalisation: from The Neighbourhood Project

There are the top-line stats to look at: nine projects, eight local government councils, over 100 community leaders trained and activated, one council process deep dive, and the development of online placemaking resources. Already, tens of thousands of individuals have been impacted for the better by The Neighbourhood Project.

Three projects in particular demonstrate the huge strides can be achieved when existing communities are given ownership, empowerment and skills over the revitalisation of their local spaces.

In 2017, community groups from Strathmore in the inner north, Edithvale in the south-east, and Williams Landing in the outer west, successfully competed to be included along with three other brilliant projects in The Neighbourhood Project, winning out of 91 applications from across the city.

The six month program comprises a series of bootcamps, workshops, mentorship and seed funding, taking the initial building block of their desire to improve their local neighbourhood and turning it into an actionable placemaking plan that would unlock hundreds of their local citizens to partner and participate with them.

Each project set out to achieve adaptive reuse of underutilized space, but the outcomes stretch far beyond, measured on the pillars of People, Process, and Place. In all cases, the end accomplishment was that of leaving a stronger, more resilient community. This is the legacy for which urban revitalization should continue to strive.

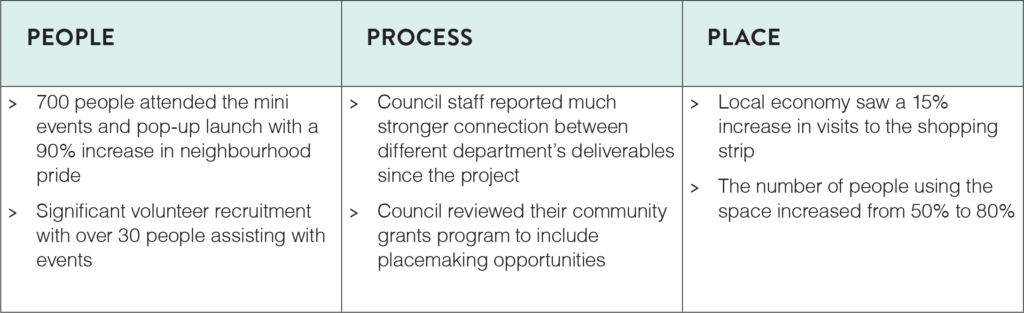

Edithvale Collective

New public artwork to reflect the revitalized place identity and character of the beachside neighbourhood of Edithvale.

A run-down beachside shopping strip next to an underutilised park reserve was brought to life by a new collective of residents and local traders.

The ideation and engagement steps led them to uncover significant place barriers that were both functional (disability access, signage, seating, bike parking, reasons to gather), as well as beautifying (plain space, vacant shops, empty garden boxes).

Their resulting program delivered a Morning Tea pop-up, Mural Art installation, Street Greening initiatives, and then a Pop-Up Park trial.

More than 4000 hours of volunteer time was unlocked by the project.

“[IT’S HELPED] MEETING MORE LOCALS, GAINING THE CONFIDENCE TO ATTEMPT PROJECTS LIKE THIS, A SENSE OF PRIDE AT WHAT WE’VE ACCOMPLISHED, AND THE STRONG FRIENDSHIPS I’VE MADE WITH THE OTHER MEMBERS OF THE GROUP.” – EDITHVALE COLLECTIVE MEMBER

Watch Edithvale Case Study video.

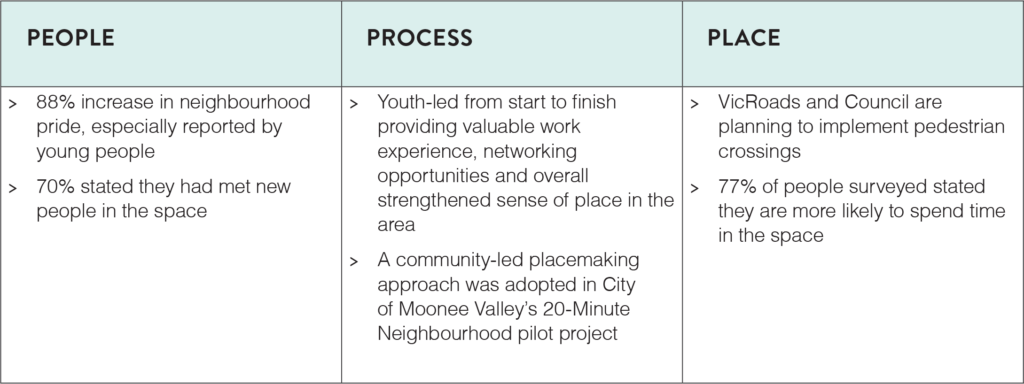

Strathmore Let’s Make A Park

The entirely youth-run project in Strathmore saw vibrancy and greening restored, boosting local capacity to lead, and creating new positive relationships with local council.

Despite an influx of residents aged under 25, Strathmore had limited public space targeting young people.

A tree in a roundabout represented the only green space in the area; an uninviting grass area, unsafe to access and for the most part unusable.

Two university students enlisted a committee of eight members and a volunteer group of twenty, aged from 12 – 25 years. Using native plants and recycled goods, the youth-led group built a new park complete with new planters, a street library of books, and a new art mural.

Their analysis of walkability has triggered VicRoads to redesign a masterplan of the intersection for safety, and the group has been engaged by council to contribute to its 20-Minute Neighbourhood Strategy.

“THERE IS NOWHERE IN STRATHMORE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE TO HANG THAT DOESN’T COST MONEY, OR EVEN ACCESS GREEN SPACE. WE WANTED TO BUILD A PARK FOR YOUNG PEOPLE, BY YOUNG PEOPLE” – STRATHMORE GROUP LEADER

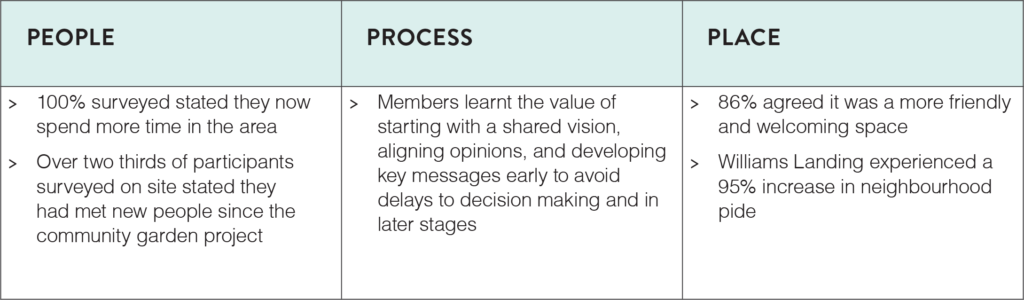

Williams Landing Community Garden

The Williams Landing Community Garden is now been upheld as “best-practice” for Melbourne’s Greening the Pipeline masterplan.

The Williams Landing Residents association converted an 80 metre by 20 metre patch of vacant land into a green and sustainable community garden.

This project illustrated the benefits of creating a place where neighbours can meet around a physical task; this was shown to accelerate opportunities for meeting new people, as well as promoting interaction and cohesion.

The result is an ongoing vibrant space, with events and picnics for connection, as well as knowledge-sharing workshops to promote sustainable environmental practices. The land sat on top of a decommissioned 1890’s pipeline, the whole 27km of which is set aside to become a linear park by Melbourne Water.

Thanks to community action in partnership with council, The Neighbourhood Project methodology is being upheld as “best-practice” for the remainder for the Greening the Pipeline Master Plan. This is predicted to lead to increased local agency and greater community connection all the way along the 27-kilometre stretch of heritage-listed land.

“IT’S BRINGING THE TWO SIDES OF WILLIAMS LANDING TOGETHER,

ACTIVATING THE PARK AND GIVING THE COMMUNITY A REASON TO COOPERATE.” – PARTICIPANT

Scalable methods, means that you too can make a difference

Today, if you visit these locations, you will find instead: a community garden upon the heritage-listed pipeline bringing neighbours together around skills and sustainability; a youth-run public beautification project that has triggered a government-led safe walking redesign for the intersection; and a reinhabited mainstreet completed with activated local park and measured boosts to local trade and neighbourhood pride.

How can a placemaking program drive such change in such a short space of time with relatively low funding requirements? The answer, is locally-led placemaking supported by a collaborative council and place authority environment.

Now, CoDesign Studio is scaling the key learnings from this program into globally-accessible resources in an endeavour to take this moment into a movement by empowering more communities and local governments to take simple actions that have been tried and tested to make long-lasting change.

Join us in applying the same principles in your own area, no matter where you are around the world. Together, we can make a difference.

About the Author:

Eliza Charley is a Strategic Operations Consultant to CoDesign Studio in Melbourne, Australia.

She is a writer, speaker, screen producer and businesswoman who has worked in industries as varied as urban development, corporate consulting, interior design, and film and television.

Wherever she is planted, she works towards delivering projects that promote people’s sense of belonging whether that be in a physical space or through storytelling.