The Guest Article for REVITALIZATION was written by Don Smith.

In the past, many developers have shied away from revitalizing large, complex brownfield sites because of the unique and onerous challenges they present.

But in a thriving commercial real estate market, where prime development sites are scarce, brownfields present an opportunity.

Over the last decade, properties with infrastructure, no environmental issues and a clear market have sold and been developed quickly.

If the economy continues to grow, and the demand continues to grow for large blocks of space, redeveloping brownfields may be the best alternative.

Unlike shovel-ready sites, brownfield properties are not in short supply.

Regions all across the country have been unable to dispose of these large, abandoned sites, and they have languished for years.

They are not just an eye sore but a depressing reminder to communities of their economic decline.

While undertaking complex environmental clean-ups and infrastructure construction on a brownfield site can be costly and complex, developers that take on these projects and do them well, can become catalysts for economic turnaround.

Seeing such a project through to the end, even in the face of daunting obstacles, goes a long way to building stronger relationships with the community residents and local government officials. They want jobs, tax revenue and to see economic prosperity return to their community.

They also want developers who can be responsive to their needs, while bringing private sector expertise and experience to the table.

Developers who help communities realize their goals will find partnerships and alliances as well as a smoother path to various forms of government funding and loans.

Success with this type of large economic development-oriented project also requires partnering with private institutions that have a public mission, like universities.They are producing much of the talent economy-driving companies need, as well as spin-off companies that are driving future growth. There is a natural synergy between these institutions and developers who share their public service vision.

Since the 1980s, Regional Industrial Development Corporation (RIDC) has successfully taken on numerous brownfield projects across Southwestern Pennsylvania. Developers wanting to do the same in other post-industrial communities will need to:

- Form strong community partnerships;

- Have the financial wherewithal and willingness to sustain their commitment to brownfield sites and market them over what may be a long haul;

- Have the tenacity, patience and balance sheet that will support them over a long time horizon, even when the project becomes more challenging than foreseen;

- Redeveloping brownfields is not a race. In order to keep costs and timeframes under control, chip away at the project piece by piece. In our experience, that has meant remediating and building for one tenant at a time.

Our strategy for attracting tenants to repurposed brownfield properties can be used by other developers and communities, as well.

To make up for a blighted appearance, it’s important to offer large indoor and outdoor amenity rich spaces and attractive prices.Companies in new and growing industries need such incentives to leave the more popular sites found in central business districts.

In new, tech-based industries, such as additive manufacturing, artificial intelligence and automation, companies have a unique need for large amounts of space that supports tinkering, outdoor testing and laydowns.

These sorts of features are becoming scarce and expensive in central business districts, but brownfields have an abundance. Developers can market the urban fringe, of which many brownfields sites sit, as a cost-effective alternative.

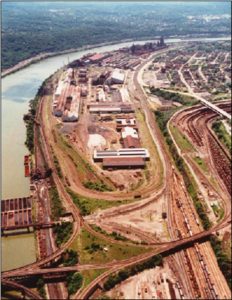

In the greater Pittsburgh region, Industrial Center of McKeesport and City Center of Duquesne are two examples of brownfield properties on the cusp revitalization and economic turnaround. They exemplify the kind of success developers can achieve when approaching complex projects with a long-term view.

Industrial Center of McKeesport was formerly the site of a National Tube Works plant, which originally opened in 1870, but eventually merged with US Steel’s Duquesne Works. It operated until the American steel industry collapsed in the 1980s.

Starting in 1990, work for environmental remediation, selective demolition and the sale of miscellaneous scrap at the site was completed in phases, followed by the renovation and conversion of four existing buildings and the construction of two new facilities.

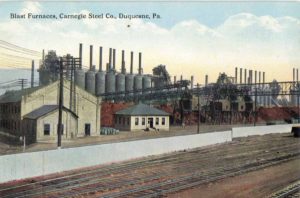

City Center of Duquesne is a former Duquesne Steel Works site. Redeveloping this site began in the late 1980s when the adaptation of existing industrial sites was not common, and the framework we developed for tackling this site led to new state legislation. Since then, six existing buildings have been renovated on the site.

It took decades of remediation and redevelopment work, but now Industrial Center of McKeesport is home to eight companies employing over 200 people, and City Center of Duquesne houses 15 companies that employ nearly 700.

Due in part to the success of these revitalized brownfield properties, the seeds of revitalization are finally taking hold and the region’s communities are showing considerable economic promise.

Development deals are happening at a more rapid pace than at any time in recent history. Just recently:

- The State of Pennsylvania announced it would fund environmental remediation work at other old industrial sites and grant the City of McKeesport $3 million to improve its housing stock, develop its downtown area and increase recreation and tourism;

- United States Steel Corp. announced a plan to reinvest $1 billion in two of its Mon Valley plants;

- Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank received a $1 million grant from the State’s Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program; they are planning a facility renovation that will expand their cold storage area, as well as their cold dock, allowing them to double the amount of fresh produce they provide to needy people throughout Western Pennsylvania by 2025;

- River Materials Inc., a supplier of raw materials, bought 8.32 acres in McKeesport for $461,700. The company began development for a new intermodal facility on 18 acres of the former U.S. Steel National Works. The remaining 9.68 acres are currently leased to River Materials, but could be sold to the company as early as the end of 2020. The facility will employ approximately 50 people;

- Two redevelopment proposals are being considered by Allegheny County for the long vacant 168-acre Carrie Furnace site. The Davis Companies, a Boston-based developer, proposes to build tech-flex buildings on one side of the Monongahela riverfront, while the Pittsburgh Film Office and RIDC are working on a proposal to bring a piece of Hollywood to another section of the site;

- Mon Valley Alliance has been busy with deals at its Alta Vista Business Park, including a new North American headquarters of Apex North America, which is expected to employ 100 people;

- Fifth Season’s new robotic vertical farming operation is coming to a 60-acre site assembled by the County next to the U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Works in Braddock; and

- Other big wins include companies such as Dura-Bond Industries expanding steel production in McKeesport, American Textile Co. expanding its operations in Duquesne and McKeesport, and the new InCity Farms, which plans to build a $30 million aquaponics and indoor farming operation in Duquesne.

Going forward into the next decade, developers should consider being more open-minded about revitalizing brownfield sites.

Those that think creatively, have longer time horizons and a healthy risk tolerance can become catalysts for job-creation, investment, and economic growth.

They’ll earn a valuable reputation for brightening the futures of the communities they work with.

About the Author:

Donald F. Smith, Jr., Ph.D is the President of RIDC of Southwestern Pennsylvania. He is a nationally recognized expert in regional economic development, with a wide variety of work experience at the local, regional, state and national levels. With a unique blend of academic and practitioner experience, Don’s work has focused on how regions can leverage and complement their innovation institutions.

President of RIDC since 2009, he has also served as a lead analyst on the statewide economic development strategy Investing In Pennsylvania’s Future in 1987, through work on the Regional Economic Revitalization Initiative, and key roles in the formation of Innovation Works in 1998, The Pittsburgh Digital greenhouse in 1999 and the Life Sciences Greenhouse in 2000.

Don held the nationally unique role of VP of Economic Development for both Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh – the first such collaboration between unaffiliated universities to advance regional economic development.