This Guest Article for REVITALIZATION is written by Neil Kitching.

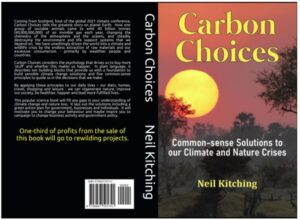

In September of 2020, my new book on climate change and nature, Carbon Choices, was published. It shows how climate change and nature are interlinked; why businesses need to reduce, reuse, repair, remanufacture and recycle; and how we can restore land-use and nature through regenerative agriculture and rewilding. Here’s what inspired me to write it.

I wrote Carbon Choices from a frustration that people are still unaware of the basic facts around climate change and its serious implications. Incorporating nature loss into the book is ambitious, but necessary, as nature is integral to climate change and wildlife is fragile. This book was instigated by my alarm that society is still not taking these issues seriously despite the science being increasingly more certain and the warnings becoming more alarming.

I wrote Carbon Choices from a frustration that people are still unaware of the basic facts around climate change and its serious implications. Incorporating nature loss into the book is ambitious, but necessary, as nature is integral to climate change and wildlife is fragile. This book was instigated by my alarm that society is still not taking these issues seriously despite the science being increasingly more certain and the warnings becoming more alarming.

The announcement of the United Nation’s climate conference to be hosted by the Scottish city of Glasgow in 2020 (rescheduled to November 2021) catalysed me into writing urgently.

Carbon Choices tells the most remarkable story on planet Earth. How one group of sociable animals came to emit 40 billion tonnes (40,000,000,000) of an invisible gas each year, changing the chemistry of the atmosphere and the oceans, and steadily destroying the environment and life support systems that we depend on. We have unwittingly driven the world into a climate and biodiversity crisis by the endless extraction of raw materials and our excessive consumption – primarily by wealthier people and countries.

Waterhole in Namibia. The four “elephants in the room” regarding climate change are consumption, beef, concrete and cooling.

Carbon Choices explores the impact of humans – population and consumption – and the reasons why it is so difficult to tackle climate change. We all know and understand that the use of electricity, driving, flying and heating our homes drives our carbon emissions. But the four ‘hidden’ elephants in the room are our excessive consumerism including fast fashion, our dietary demands including beef and dairy, society’s use of cement and concrete, and the refrigerant gases and energy used for cooling.

Carbon Choices identifies ten building blocks; including sensible economics, regulations, design, innovation, investment, education and behaviour change. These ten building blocks are the foundations to help us build a low carbon economy that works in harmony with nature.

Without these in place, tackling climate change is at best, an uphill battle. Those who try to be ‘green’ find there are obstacles – we need to clear these. Governments can then set the policy direction and sensible regulations, businesses can respond and provide innovative low carbon products and services, and consumers will have the knowledge to make better carbon choices.

Businesses

Businesses should design products using the ‘circular economy’ principles; as championed by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Ellen MacArthur gained the world record for the fastest solo circumnavigation of the globe in 2005. On that voyage she realised that the world is finite and learnt to minimise her use of resources. The three circular economy principles are:

• Design out waste

• Keep products and services in use

• Regenerate natural systems

To reduce our consumption of virgin raw materials and our need to continually buy new products the four ‘R’s are also relevant – Reuse, Repair, Remanufacture and lastly Recycle. Many commentators would insert an extra ‘R’ before these – to Reduce our consumption.

Weigh Ahead is a charity and community owned shop in Dunblane. It aims to reduce, or eliminate single use plastic packaging. Customers bring their own containers, have them weighed, fill them up then pay for the weight of product purchased. A few supermarkets are tentatively trialling similar ideas.Products should be designed to be resource effective; that is to minimise the overall use of resources over their lifetime. Minimising the quantity of raw materials required and minimising any waste during its manufacture, use or end of life will help.

Some designers already do this to a certain extent. But the price of many materials and components does not reflect their environmental damage and are so cheap that the price incentive does not work effectively to reduce our consumption of raw materials. It is possible to reduce the need for raw materials by making things smaller, with less waste in the manufacturing process or by using strong or light materials.

For example, the UK’s National Grid has built traditional ‘A’ shaped high-voltage electricity pylons since 1928 with little change in design over this period. Recently they ran a competition to design a more efficient and aesthetically pleasing design. The winning design was a ‘T’ shape that uses far less steel and is visually less intrusive as its maximum height is 38m versus 50m for traditional pylons.

If products are designed to last a long time, then this will reduce our need or desire to buy new. The cheapest price often directs or attracts consumers to buying a product, but often this does not benefit us in the long-term.

For example, you can buy poor quality magnetic learner driver plates for one pound. They are cheap and convenient, but as soon as the learner driver starts driving faster, or drives on a windy day, the plates fall off and litter our roadsides with plastic and steel. Magnetic plates can work but they need to be designed with stronger, better quality, magnetic material.

Offering a long guarantee when selling a product would incentivise manufacturers to build quality long-lasting products and offers comfort to the consumer. Some new cars come with a seven-year guarantee and a few products, such as Tilley hats and Parker pens are sold with a lifetime guarantee. Clearly it is initially more expensive to pay for this level of quality, but you can guarantee that products will be designed and manufactured to a high standard, reducing the risk to the retailer of returns under the guarantee.

Agriculture

There are many who campaign for organic produce and argue equally passionately against genetically modified foods. Organic farms only use organic fertiliser, natural pesticides and use techniques like crop rotation, mixed crops and encourage natural insect predators. They ban synthetic fertiliser, pesticides; and growth hormones and routine antibiotics in livestock.

Organic farming methods are usually beneficial to wildlife, particularly the reduction in herbicide and pesticide use, and it often goes hand in hand with a farm that manages its soil better and has more land set aside that is not intensively cultivated. Insects, such as pollinating bees and moths, can thrive in such a landscape. Reduced fertiliser run-off into rivers improves water quality.

But organic farming usually produces a lower yield than intensive agriculture using synthetic fertiliser. So, a counterargument is that moving to organic farming would require more land to produce the same amount of food with negative consequences on the area of remaining land available for wildlife. Despite, using no synthetic fertiliser, greenhouse gas emissions can be higher because of this lower crop and livestock productivity.

The debate is polarised. But there may be a sensible compromise between the two extremes of organic and intensive agriculture that will avoid the overuse of synthetic fertiliser, maintain long-term fertility of the soil and feed a growing population. Regenerative agriculture is an approach that aims to enhance the soil, land, water quality and wildlife.

The techniques are to minimise tillage, always keep soil covered by plants, plant a diversity of crops and possibly to integrate livestock into arable farming. These will increase the micro-biology in the soil making it naturally more fertile, reduce soil compaction, and consequently improve water quality downstream through less erosion and nutrient run-off. Although it has similar aims to organic farming, the criteria are not so strict. Regenerative agriculture focuses more strongly on reducing expensive inputs to fields and avoiding ploughing. This reduction in cost will boost farm profits.

After many decades of encouraging over production, EU farm subsidies have slowly begun to be redirected towards paying farmers for environmental improvements – although this should go much further. Farmers can be paid for setting aside part of their land for new woodland, or to grow wildflowers to encourage biodiversity and bees in particular.

Nature

Traditionally we have ‘conserved’ wildlife and nature, protecting the best bits that remain in designated nature reserves. Reserves are actively managed to provide habitat for selected species.

Often this means keeping wildlife and people apart or at least restricting access to certain areas.

Rewilding turns this on its head. Natural processes dominate, allowing nature and species distribution to evolve over time. Rewilding applies to rural areas and to our towns and cities and can envisage people living with nature. It is a positive vision for the future.

Small steps have already been taken to rewild certain areas in Scotland, trying to recreate natural processes before modern humans altered or destroyed it. Intrusive timber plantations in the Caithness Flow Country have been removed to restore the natural peatland. In Glen Affric and in the Trossachs, areas are fenced to keep grazing animals out. Native trees have been planted and after only a few years birdlife returns. In fact, once the grazing pressure is reduced, trees start growing spontaneously after three or four years. Artificial obstacles to fish migration in rivers such as weirs are being removed.

Beavers have been reintroduced to forests in Knapdale and the River Tay catchment. Like elephants and ants in Africa, they are a ‘keystone’ species, which manipulate and alter the landscape. They gnaw through small deciduous trees to build dams. This creates temporary clearings and wetland which create new habitat for insects, fish, amphibians and birds. Wetlands store more water which can reduce peak-flows and flooding downstream, although farmers do not always welcome these new wetlands on their land.

We should restore much of this natural forest, focusing on areas that are of marginal use for agriculture, but also some areas of prime productive land. Imagine if we restored a vast Caledonian woodland habitat in the Highlands of Scotland stretching as far as the eye can see.

There would be free flowing wild rivers and wetlands, moorland and mountains rising above the natural treeline. Fish, birds, amphibians and mammals could thrive again. Large grazing animals and predators could be reintroduced. Certainly, the lynx, perhaps bears and wolves but only once the restored area is large enough. Wolves are making a comeback in mainland Europe, including densely populated Belgium, so why should Scotland be any different, other than we have destroyed the natural habitat that they can thrive in?

This Scottish Caledonian woodland habitat would not be a complete wilderness, but there would be space for wildlife to move around within it, with woodland corridors linking it to other restored forests across the UK. And it would not be continuous forest. Herbivores, large and small, have different grazing habits that create a mosaic of open and forest habitats, whilst their manure spreads nutrients across the countryside to benefit plants and insects.

Rewilding is not just about the land. Many rivers and seas have been devastated by pollution and over exploitation. Whale hunting is an obvious example but there are many others. Off the Scottish coast, dredgers have scoured the seabed for scallops, effectively raking the seabed and disrupting everything that lives or grows there. This is short-termism by fishermen as it then takes much longer for the scallops to recover.

The Firth of Forth had the largest oyster beds in the world in the 18th century. The development of heavy rakes dragged along the seabed enabled people in rowing boats to collect 30 million oysters in a single year. This overfishing, and the lack of any effective management, led to a collapse in the oyster population and eventual extinction from the east coast of Scotland.

More recently, the government has established small Marine Conservation Areas. Following a community led campaign; a small ‘no-take’ area was established off the island of Arran in 2008. Studies have shown that wildlife is recovering naturally. King scallops and lobster density is higher, carbon absorbing seagrass has returned to the seabed and the area is now a nursery for juvenile fish, especially cod. By protecting even a small area the benefits accrue over a wider area which can enable sustainable commercial fishing to take place.

The Forth Rivers Trust has taken small steps to transform the Allan Water, a river in Scotland. The riverside landscape is picturesque, but ecologists and hydrologists will notice that after rain, its waters turn muddy as soil and peat washes off fields and moors. This silt can harm fish such as salmon. Humans have completely altered the river’s catchment. Farmers and landowners have removed the natural forest cover, drained peat bogs and canalised stretches, whilst invasive species such as giant hogweed are rampant.

Now, the Trust is blocking drains to raise the water table in peatland high up in the catchment. This enables moss to regrow – in effect acting as a giant sponge. Invertebrates, amphibians and birds are returning to these bogs. Trees planted along the riverbank shade fish, stabilise the banks and reduce soil erosion. These actions help to store carbon on the land and reduce the risk of flash floods. Attempts are being made to control invasive mink and giant hogweed. There are plans to remove barriers to fish migration and to restore the original meanders, in effect to rewild the catchment. But lack of funds limits action on the ground.

Conclusion

Amidst all the bad news, there are grounds for hope. We can regenerate nature and our lives if we choose to do so. My new book concludes with a green action plan so that government, business and individuals can make better carbon choices.

I wrote it for those interested in restoring our environment, for young adults studying geography and for anyone interested in the environment and their future.

Carbon Choices is available as a paperback on Amazon and e-book on Kindle. One third of all profits will be donated to rewilding projects. Or, learn more about Carbon Choices here.

All photos are by Neil Kitching.

About the Author:

Neil Kitching is a geographer and energy specialist from Scotland.

Neil Kitching is a geographer and energy specialist from Scotland.

He has written his first book, Carbon Choices on the common-sense solutions to our climate and nature crises. He works for a public sector agency promoting the opportunities for business to benefit from low carbon heating and water technologies.

This book arose from Neil’s frustration that so many people lack a basic knowledge of climate change and its impacts on people and nature. Education is the first step towards taking action.