It is time to rethink how we deal with vacant and abandoned properties. Almost a decade since the housing bubble burst, there are still 1.3 million vacant residential homes in the U.S.

This includes areas that were the hardest hit during the great recession, such as Florida with 180,800 vacant homes, Michigan with 117,800, Ohio with 86,400 but also Texas with 117,000 and smaller states like Mississippi and Alabama where more than one out of every 40 homes is vacant.

Vacant and abandoned properties impose major costs for neighbors, communities, municipalities and society. Quantifying these costs is challenging but even using conservative estimates, the costs are substantial.

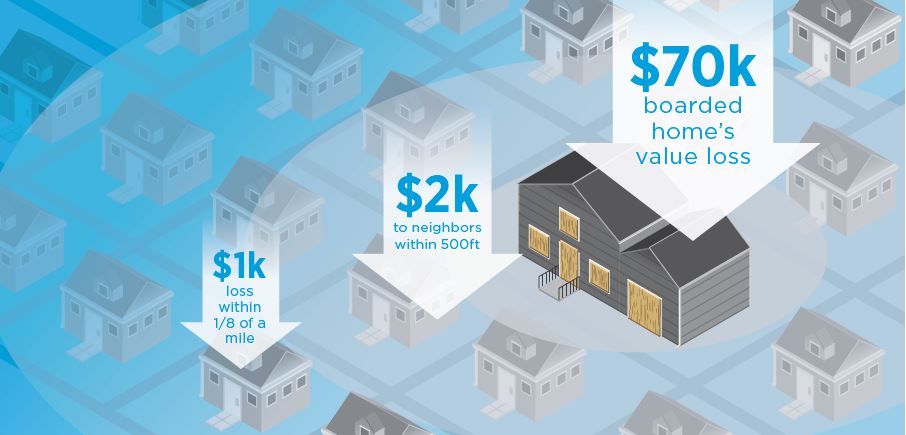

A single, foreclosed, vacant or abandoned home that is improperly secured can result in economic loss for not only the property itself, but also to neighbors surrounding the property, as well as the broader community. Specifically, for the median home worth approximately $200,000, the foreclosed and abandoned house itself loses $70,000 in value, imposes close to $100,000 in property value loss to its surrounding neighbors, is responsible for $14,000 worth of crime per year in the immediate community, and is associated with $1,500 in police and fire department costs per year in municipal budgets.

This paper’s conservative estimate is that the typical foreclosed home imposes costs of over $170,000. The majority of these costs, around $85,000, are directly attributable to being vacant and the condition in which that vacant house is kept. Fortunately, there are common sense, practical and affordable remedies

that can help reduce these costs, create value and reduce the negative externalities caused by vacant and abandoned properties.

This paper examines the main drivers of the cost of abandoned properties to uncover a surprisingly simple path forward to mitigate some of this harm. It begins by quantifying the costs associated with vacant buildings. These costs may appear self-evident at first – the reduction in property value for the building, for neighbors, for the community – but they are often broader than commonly appreciated: major costs stem from increased crime and arson generated from abandoned properties.

The paper expands the analysis to consider how abandoned buildings and associated community blight add to the number and cost of foreclosures. These costs have been shown to linger over time, adding another dimension to the analysis.

The final section of analysis focuses on what affects these costs. The key finding is that maintenance of the property, what condition the property is in, has a large impact on both the direct and indirect costs. Maintenance is a broadly defined term, and this paper explores specific questions regarding what types of maintenance make a difference. The result of this analysis is the conclusion that how a building is secured can have a substantial impact on the total costs that its vacant status impose on its neighbors, the community and society. It impacts future foreclosures and the costs of those foreclosures.

This finding calls into question the decades-old practice of simply boarding up vacant properties with plywood. It highlights the need for further analysis (which is underway in a soon-to-be released follow-up paper) into superior methods of securing vacant properties, such as using polycarbonate or clearboarding.

This analysis sets the stage for answering the simple question, what are the economic costs and benefits to securing a property through different methods? Are there methods that while more expensive than the traditional, business-as-usual plywood produce overall net savings for communities, and how do those savings reduce foreclosures?

Clearboarding has greater up-front costs, but long-term savings can exceed those costs by over 34:1. It’s also easily reusable.

(* Boarding cost basis = 2 doors + 5 windows)

Economic study is important but should not be considered in a vacuum. Given the magnitude of vacant buildings, some forward-thinking public and private enterprises have already begun to experiment and will reap the benefits. Recently, the nation’s largest mortgage owner, Fannie Mae, announced that it was embracing alternative methods of securing buildings, including clearboarding.

Cities such as Detroit and Chicago have adopted this technological improvement as well. However, the economic benefits of this alternative, particularly the positive externalities – the benefits that spill over beyond the vacant property to neighbors, communities, local and state governments, and society at large have not been fully appreciated. Broader appreciation of those benefits starts with a greater understanding of the costs of vacant houses.

In January of 2017, Ohio became the first state to ban plywood boarding on vacant and abandoned properties when Governor John Kasich signed into law HB 463. The groundbreaking legislation is a bold statement that will lead to increased use of polycarbonate clearboarding and modernize the fight against blight in Ohio.

In January of 2017, Ohio became the first state to ban plywood boarding on vacant and abandoned properties when Governor John Kasich signed into law HB 463. The groundbreaking legislation is a bold statement that will lead to increased use of polycarbonate clearboarding and modernize the fight against blight in Ohio.

In November 2016, Fannie Mae announced that it was expanding its reimbursement criteria to include polycarbonate clearboarding as a method to secure vacant properties, whether they are real-estate-owned or in a pre-foreclosure state.

Brandon Johnson, CEO of property preservation company GTJ Consulting in Detroit, told DS News in May 2016: “We try to explain that the benefits, in our mind, far outweigh the additional cost, because it’s a long-term solution. You can’t get in, you can’t break through it, and it withstands the elements. It doesn’t disintegrate over time, and it looks much better, because when you drive by, you can’t even tell that the property is boarded up. On a number of levels, we feel it’s a great product, and a definite step forward in the urban fight against blight for communities.”

See full January 2017 “cost of blight” report (PDF).

See full February 2017 polycarbonate report (PDF).

See Community Blight Solutions website.

Watch 1-minute video about polycarbonate use.

See April 4, 2017 AP article announcing the Day One of Ohio’s plywood ban.

About the Author

Aaron Klein previously served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Department for Economic Policy and Chief Economist of the U.S. Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee. In those positions Klein played a major role in the response to the 2008 financial crisis, including leading work on housing policy and finance reform on such legislation as the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (TARP), and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. A leader in the field of housing and finance policy, with over a decade of senior-level experience, he has served as a consultant and economist in providing clients with expert analysis and innovative solutions. This paper was funded with the support of Community Blight Solutions with the data, research and opinions those of the author. Klein previously directed the Financial Regulatory Reform Initiative at the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington, D.C. Klein is a frequent author and commentator on major issues cited extensively in US and international media, including The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, BBC, CNBC, Fox Business News, Politico, LA Times, The Guardian, The New Yorker, and National Public Radio.

Aaron Klein previously served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Department for Economic Policy and Chief Economist of the U.S. Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee. In those positions Klein played a major role in the response to the 2008 financial crisis, including leading work on housing policy and finance reform on such legislation as the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (TARP), and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. A leader in the field of housing and finance policy, with over a decade of senior-level experience, he has served as a consultant and economist in providing clients with expert analysis and innovative solutions. This paper was funded with the support of Community Blight Solutions with the data, research and opinions those of the author. Klein previously directed the Financial Regulatory Reform Initiative at the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington, D.C. Klein is a frequent author and commentator on major issues cited extensively in US and international media, including The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, BBC, CNBC, Fox Business News, Politico, LA Times, The Guardian, The New Yorker, and National Public Radio.