In September of 2005, as part of the Department of Defense 2005 Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process, the decision was made to close the Naval Air Station Brunswick (NAS Brunswick). The Navy ceased operations at NAS Brunswick in May 2011.

Located in Maine’s mid-coast region, the 3,200 acre NAS Brunswick and associated facilities had been a mainstay in the small town of Brunswick since 1943. At the time of the BRAC decision, NAS Brunswick was Maine’s second largest employer, employing 4,863 military and civilian personnel.

The air station provided over $187 million annually to the local economy in payroll, contracts and purchases. While the closure had a profound impact on Brunswick, the Mid-Coast community, and the state of Maine, economically and socially, the rapid recovery has been a source of pride for all.

NAS Brunswick – A brief history

NAS Brunswick was originally constructed in March, 1943 and was first commissioned on April 15, 1943. The Station’s primary mission at the time was the training of Royal Canadian Air Force pilots of the British Naval Command. NAS Brunswick’s first commanding Officer was Navy Commander John C. Alderman, who later attained the rank of Rear Admiral.

Opening under the motto “Built for Business”, the first U.S. Squadron to arrive at NAS Brunswick was Heavier-than-Air Scouting Squadron (VS-1D1). During World War II, Pilots from NAS Brunswick, as well as those from the Royal Air Force used the station as a base from which they carried out anti-submarine warfare missions. At the peak of its wartime operations, the station was supporting three auxiliary landing fields – one at Sanford, one at Rockland, and one at Lewiston, Maine. Once the war ended, NAS Brunswick was scheduled for deactivation.

Upon deactivation in 1946, the land reverted to caretaker status and was used for the University of Maine, Bowdoin College and a Town airport. In 1951, as a result of the cold war heating up, NAS Brunswick was re-established. New construction around the base was begun which included the dual 8,000-foot runways, and new facilities to replace the temporary structures of WWII.

At the time of the BRAC decision, NAS Brunswick’s primary mission was the support of naval aviation activities in the northeastern United States. Naval Air Station Brunswick was home to five active duty and two reserve squadrons; flying Lockheed P-3 “Orion” long-range maritime patrol aircraft tasked by Patrol and Reconnaissance Wing Five. NAS Brunswick had 29 tenant commands, including: five active squadrons, a reserve P-3 squadron and a reserve fleet logistics support squadron flying C-130 “Hercules” transports. In addition, over 1,600 Naval Reservists traveled from throughout New England to drill at Naval Air Reserve Brunswick, SeaBee Battalion and numerous other reserve commands. NAS Brunswick was the last, active-duty U.S. Department of Defense airfield remaining in the northeast.

After being listed on the 2005 BRAC list, the U.S. Navy and NAS Brunswick began preparing itself for shut down with a 2011 closure date. In May 2008, Captain William A. Fitzgerald relieved Captain George Womack to become the 36th and final Commanding Officer, tasked with the responsibility of closing the base (U.S. Navy, 2011).

Preparing for Closure and Planning for the Future

During the deliberations of the BRAC Commission, the affected communities, the State of Maine and Maine’s congressional delegation were aggressive in trying to keep NAS Brunswick open; to no avail. In fact, the preliminary decision of the Commission was to re-align the installation, which meant that it would just be maintained as an auxiliary facility with all the units moved. Fearing that the property would be mothballed and not be available for redevelopment, the Town asked for a full closure.

Upon learning of the BRAC Commission’s final decision to close NAS Brunswick, there was significant public trepidation about the impending action. The local communities and State were devastated with the loss of this regional and State economic driver, but hopeful that the future would hold new promise. Brunswick and the surrounding local communities were concerned about the economic impacts including a housing glut and loss of federal aid for education due to less military family children in school.

Predicted impacts of the closure of NAS Brunswick included (Maine State Planning Office, 2007):

- The Brunswick LMA was expected to see the loss of upwards of 6,500 jobs and $140 million of annual income by 2011;

- The State’s Gross State Product was predicted to be reduced by nearly $400 million annually;

- Area employers were predicted to lose approximately 500 military spouses as their employees;

- Approximately 2300 housing units would be entering the marketplace, which would contribute to an increase in the regional vacancy rate to about 10%;

- The Brunswick area will see a loss of approximately $14 million in rent and mortgage payments;

- Local public schools will lose 10% of their students and nearly $1.3 million in federal school aid.

Soon after the closure decision was made in 2005, the State of Maine and the Town of Brunswick established the Brunswick Local Redevelopment Authority (BLRA) to begin the process of hiring staff to prepare the Master Reuse Plan for the 3,320 acre main base, and the Town of Topsham established the Topsham Local Redevelopment Authority (TLRA) to prepare the Reuse Master Plan for the 74 acre Annex in the adjacent Town of Topsham. The BLRA hired Steven Levesque, an experienced planner and economic developer and a former Commissioner of the Maine Department of Economic Development to lead the Brunswick effort. The Town of Topsham slated their Town Planner, Richard Roedner, to lead their effort.

Both the BLRA and TLRA hired the same planning consulting teams to assist with their respective planning efforts, headed by the Matrix Design Group, based in Denver, Colorado. In addition, the State formed an Advisory Committee to address regional “outside the gate” matters focusing on such issues as transportation, housing and economic development.

The development of the Master Reuse Plans for the NAS Brunswick properties was substantive and involved significant public participation. Over an eighteen month period from April of 2006 through November of 2007, the reuse planning processes involved substantial asset mapping, natural resource inventories, infrastructure assessments, economic analysis and forecasting, an airport feasibility study, land use planning studies, and the development and execution of a robust and thorough public outreach and participation process.

The public outreach and participation process involved a number of key elements, including:

- conducting of a series of base bus tours called “Bus to Base” tours, aimed at familiarizing the public with the base assets;

- holding several distinct public workshops involving the general public, the base civilian workforce and local high school students;

- conducting several topical seminars on various issues associated with base closure, such as environmental remediation, energy, utilities, land use, etc.;

- conducting of several public visioning workshops to do SWOT analysis and review and discuss various land use scenarios;

- conducting a “smart growth” planning charrette.

- conducting an airport feasibility study sessions to discuss opportunities and options associated with the aviation facility;

- conducting a region-wide re-use survey of area residents and businesses;

- developing a newsletter and website to provide on-going updates and solicit public opinion;

- conducting over 40 presentations to community and business groups;

- holding tours for media members and provided regular editorial commentaries; etc.; and;

- televising all Board meetings.

The end result produced reuse master plans that were widely supported by the residents and businesses of the region and were feasible and implementable within the local, regional and State socio-political systems within the locale of the former base installation. On December 19, 2007, the Board of Directors of the BLRA and TLRA unanimously adopted the Reuse Master Plans and authorized the submission of the Plans to the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (for the homeless assistance plan component) and the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority (BLRA and TLRA’s successor).

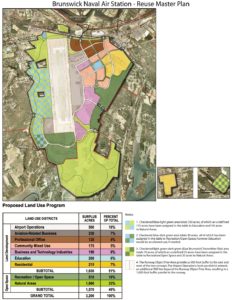

Figure 2: Brunswick Naval Air Station – Reuse Master Plan (Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority)

The Brunswick Reuse Master Plan includes a range of uses: airport operations and aviation related businesses, business and technology industries, alternative energy research, manufacturing and power generation, higher education, residential housing, recreation, and open space.

Given the significant un-altered natural setting of the former base, nearly 50% of the former base property was designated for open space and recreation (see Figure 2).

Specific business sectors for the property were established as best-fit targets for the property reuse, including: aerospace/aviation; composites and advanced materials; information technology; alternative energy; education; and bio-technology.

These sectors are still very relevant and prominent components of the redevelopment effort.

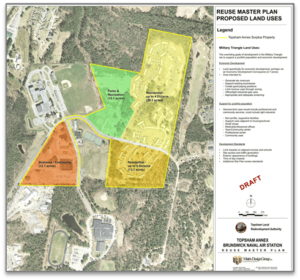

The Topsham Annex Reuse Master Plan called for community-based infill such as residential, commercial, open space and light industrial uses (See Figure 3). All of which are still relevant and prominent today.

Property Disposal Recommendation Process

As part of the master reuse planning process, there were other important required processes involved including the development of a property disposition and conveyance plan and homeless assistance plan.

To meet these requirements, the BLRA set up a State and Local Screening process and a Homeless Assistance process, and assigned a sub-committee to each.

Property conveyance mechanisms available to the U.S. Government for BRAC’d installations include: Public Benefit Conveyances, Economic Development Conveyances, Public Sales and Negotiated Sales, which are described in more detail below. In the NAS Brunswick case, only PBC’s and EDC’s mechanisms were utilized.

- Public Benefit Conveyances. PBCs are conveyances of real and personal property to State and local governments for certain nonprofit organizations for public purposes up to no cost as authorized by statute;

- Economic Development Conveyances. EDCs were created for the purpose of job generation on an installation. Only an LRA is eligible to acquire property under an EDC. No cost EDCs were most typical in previous BRAC rounds. No cost EDCs changed after the 2005 round of BRAC closures – they were amended to require the military to get fair market value. However in 2009, the law was again changed to allow for a balanced approached with “back end participation” opportunities for the government;

- Public Sale. This generally means disposing of property via an internet auction, although it can take the form of an on-site auction or a sealed bid;

- Negotiated Sale. This is a fair market value conveyance, often to a public body for a public purpose.

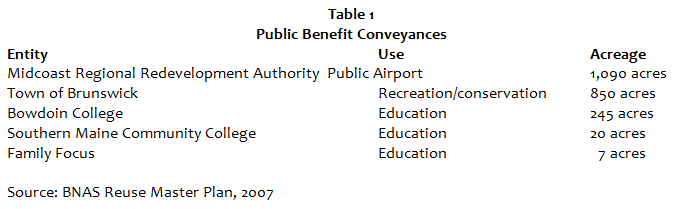

As a result of this process, several Public Benefit Conveyances were granted as part of the closure process as identified in Table 1. These included both land and the structures that were related.

The Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority was awarded an EDC for financial consideration of approximately 1,100 acres and related structures. This was a very unique real estate deal and one of the first of its kind in the 2005 round of closures. To provide some context to this transaction, it’s important to understand the historic environment of the federal property disposal process related to BRAC.

In the previous BRAC rounds prior to 1995, base properties were essentially given to the local redevelopment authorities, state or local governments through a no-cost EDC procedure after they were closed. This allowed these entities to secure some redevelopment opportunities without incurring the traditional real estate holding costs typically associated with development activities.

However, due to the real estate boom in the 1990’s, Congress determined that these high value properties could fetch good value in an open real estate market and thereby provide a return on the governments investments. In order to get the best rate of return for the military services, the desired method to dispose these properties was through the public sale process to one major developer. Indeed, public sales of a few select former base properties in California and Florida in the mid 90’s to real estate developers did realize some very high prices. But many installations either did not receive good value returns or none at all from attempted public sales (DoD-OEA, 2009).

Given some past success in value returns, the law that governed the disposal of federal properties in the 2005 BRAC round did require that the military services seek fair market values for all EDC parcels (DoD, 2005). However, several problems with this approach became evident: 1) the process did not differentiate between high value urban properties and low value rural properties, which made it highly unlikely that rural properties could attract a significant buyer; and 2) starting in 2008, the U.S. economy went into a deep recession, led by a collapse of the residential real estate market. Thus, it became clearly evident that this market driven approach would not work across the varied economic landscapes within the U.S. and it would be very difficult to redevelop many of these installations, particularly the rural properties.

To address this issue, Senator Snowe of Maine introduced Senate Bill S.590, Defense Communities Act of 2009, which would change the EDC law to allow for a less than fair market value option for the disposal of properties based upon their individual circumstances, which was approved by the Senate. A companion House bill was introduced by Representative Pingree, also of Maine, which would grant a no-cost EDC for all installations and was approved by that body. During, the conference deliberation between the two bodies, the language was modified to include the current law: 10 U.S.C. 2687. This law allows for more robust discussions to occur with the services about current economic conditions of specific properties and the opportunities to negotiate more flexible terms with respect to market values and financial considerations, based on real time situations. This new law change provided the basis of the negotiated agreement between the U.S. Navy and MRRA regarding the EDC transfer of property at NAS Brunswick and permitted the process to move ahead in a rapid fashion.

The approved EDC agreement for NAS Brunswick focused on several elements. Rather than an up-front payment requirement for the land value, which would not have been feasible, MRRA was able to negotiate a real-time economic based approach that would essentially make the Navy a partner in the redevelopment effort. The essence of this agreement provided for the Navy to receive a portion of the lease and sales revenues from the redevelopment effort over time. Specifically, there was a note with a payment of $3 million over a ten year period and a sharing of 25% of lease and sales revenues for a period of twenty-three years. As of this writing, MRRA has payed the U.S. Navy a total of $6.5 million, with an ultimate expectation of total consideration of around $10-12 million paid to the Navy when the agreement ends in 2032. As stated above, this pay-as-you go approach was much more realistic to the redevelopment effort, as it would not have been feasible for MRRA to raise approximately $15 million to pay the initial appraised value of the property. This type of approach has served as a good model for other base redevelopment efforts across the country.

It’s also important to note that MRRA was able to negotiate leases and transfers of property from the Navy prior to the actual closing of the installation. Due to a strong and trusting partnership with the Navy (including a very motivated and resourceful base commander), and cooperative environmental regulators, MRRA was able to receive a conveyance of nearly 800 acres of airport property and several building leases, months prior to the base being disestablished. This approach was a very novel concept to the military community and paved the way for similar advance conveyances at other installations in the United States. This strong partnership with the Navy enabled MRRA to get a rapid start to its redevelopment efforts and has been an important ingredient to the success of the project to date.

Accommodating the needs of the Homeless

A required part of the reuse planning process is the accommodation of the needs of the homeless as part of the Reuse Master Plan, which had to be approved by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (DoD, 2005). In meeting this mandate, the BLRA worked with the Maine State Housing Authority to identify and classify the homelessness issues in the Mid-coast region. The study concluded that the needs of the homeless in the region would be accommodated by housing subsidies and additional service assistance.

Upon completion of that study, request for proposals were sent out to known homeless service providers in Maine that reflected the homelessness needs in the region. Following a screening process, the BLRA determined that Tedford Housing’s proposal best aligned with the needs identified.

In light of the above, a Homeless Assistance Plan was developed which would establish a trust fund to be capitalize through the conveyance of developable properties at $740 per acre; estimated to generate approximately $700,000. This trust fund would be administered by MRRA to support those applicable services of Tedford Housing. The Homeless Assistance Plan was approved by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in April 2009.

National Environmental Policy Act Process

Upon completion and approval of the respective Brunswick and Topsham Reuse Master Plans, they became subject to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process. The Department of the Navy would be unable to transfer any properties until this process was completed (DoD, 2005). In compliance with the NEPA process the Department of the Navy began the process of developing an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the disposal and reuse of NAS Brunswick. The EIS presented an analysis of the Navy’s proposed action to dispose the base property consistent with the approved reuse master plan. The EIS evaluated the potential direct, indirect, short-term and long-term impacts on the human and natural environments resulting from the disposal of NAS Brunswick on a phased 5-20 year buildout scenario of reuse of the base property. Resource areas that were examined in the EIS included: land use and zoning, socioeconomics, community facilities and services, transportation, environmental management, air quality, noise, infrastructure, cultural resources, topography, geology, soils, water resources and resources. The EIS also evaluated cumulative impacts and several reuse alternatives, including a no-project alternative.

The EIS process, which included a comprehensive public scoping and input process, was finalized in November of 2010 with the publication of the Final EIS. This document demonstrated that implementation of the proposed Brunswick Reuse Master Plan would not result in a significant impact to the natural environment and man-made systems of the base property and surrounding environs (Navy EIS, 2010).

Because of the small scale of the Topsham Annex (74 acres) and the already built environment of that facility, The Topsham Annex Reuse Master Plan was only subject to an Environmental Assessment (EA) process, which is a much scaled-down environmental review of the same topical areas of the EIS. It was determined that the implementation of the Topsham Annex Reuse Master Plan would also not result in a significant impact to the natural and man-made systems of that property (Navy EA, 2010).

Following successful completion of this NEPA process, the Department of the Navy was now free to transfer properties in accordance with the disposal conveyances and other environmental conditions of the properties.

Environmental Contamination

NAS Brunswick was originally commissioned in 1943 and had been in continued use as a military installation since 1951. Unfortunately, the disposal and handling practices of chemicals and other substances used at this military facility and other facilities and industrial sites around the U.S. were much different in these time periods than current times. The end result of these past practices were large areas of land and water bodies that had become contaminated and were posing significant health risks across the country.

These problems prompted a groundswell of public concern and the beginnings of the environmental movement in the United States. This grassroots movement eventually resulted in the creation of some significant federal legislation aimed at arresting the contamination problems and cleaning-up our environment in the early 1970’s. These notable laws included the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. Several other laws regulating the management of hazardous substances followed over the years including the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act. The application of these laws, as well as other federal, state and local regulations, are key elements in the base disposal and reuse process.

As part of the federal implementation of the BRAC decision to close NAS Brunswick, the Department of the Navy was required to prepare a comprehensive report called the Environmental Conditions of Property Report. It documented, among other elements, an assessment of the environmental conditions of the base property, including the identification of restoration program sites, the identification and assessment of underground and above ground storage tanks; identification of munitions and explosives of concern; an identification of hazardous wastes, radiological and chemical and pesticide contamination; groundwater and stormwater contamination; and other environmental factors (U.S. Navy, 2006).

This information were key factors in the Navy’s development of its Installation Remediation Program, which has been on-going since the early 1980’s in coordination with the U.S. Department of Environmental Protection (EPA) and the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (EPA). The clean-up process is also overseen by a Restoration Advisory Board, comprising representatives of the Navy, the EPA, the DEP, citizen members appointed by the Town of Brunswick and MRRA.

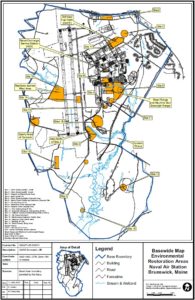

Figure 4 illustrates the current known sites of environmental contamination at NAS Brunswick. Additional sites, areas of concern and contaminants are added as additional new information is gained. It’s important to note that no property can be transferred until that property has been certified to be suitable for transfer by the Navy and it has received concurrence by both the EPA and DEP. It’s also important to note that the Navy is responsible for the remediation of identified contaminated sites and any future sites or contaminants determined to be associated with the Navy’s historical presence.

In addition, there is an abundance of legal documentation on various restrictions on land use activities that are addressed through the property transfer process. These include specific site restrictions on groundwater use and excavation and other land use controls. These restrictions are handled through a combination of property easements, deed restrictions and zoning ordinance provisions.

One example of how these environmental issues are addressed at Brunswick include the newly identified possibility that groundwater at the former base is contaminated with Perflourinated Chemicals (PFC’s).

PFCs are found in many common household products. PFC’s have been used since the 1950s in products such as non-stick cookware, food packaging, waterproof clothing, fabric stain protectors, lubricants, and paints. PFC’s have also been used in aqueous firefighting foam (AFFF). AFFF has historically been used nationwide for firefighting at airports (both military and civilian) including NAS Brunswick.

PFCs are now an emerging contaminant of concern for EPA nationwide and they are studying these chemicals due to concerns for the potential widespread exposure to humans, their persistence in the environment, their observed toxicity in animals, and the lack of information to properly assess human health risk associated with these chemicals.

As emerging contaminants that had not previously been identified by EPA as contaminants of concern, PFC’s had not been monitored or sampled for during previous investigations at NAS Brunswick (now called Brunswick Landing).

In 2014, the NAS Brunswick Technical Team (Navy, Maine DEP, and the EPA) began an evaluation of PFC’s at the former Naval Air Station (Brunswick Landing). The initial sampling program targeted potential source areas and areas of potential migration. The Navy investigation focused on sampling groundwater in areas where aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) had been used or disposed of (discharged) in the past to determine absence or presence of PFC’s. Sampling was also conducted to evaluate whether PFC’s, if present, have migrated from these potential source areas.

After an extensive records search and interview process, the Navy identified areas at which AFFF was most likely to have been used/disposed of at NAS Brunswick (Brunswick Landing). A Navy contractor conducted historical research and a site visit was conducted by a former Navy Assistant Fire Chief and Maine DEP to inspect areas where AFFF may have been used or disposed.

The Navy performed field sampling of groundwater in the identified areas in October and November 2014. Groundwater samples were collected from 21 existing monitoring wells (including 17 site wells and 4 background wells), 15 new monitoring wells, and from the Navy’s Groundwater Extraction and Treatment system. The Navy also sampled distribution (finish) water from the Brunswick Topsham Water District’s (BTWD) Jordan Avenue Pump Station.

From the Navy’s initial round of sampling PFC’s were not detected in background wells or in BTWD’s Jordan Avenue finish wells. PFC’s in exceedance of EPA and/or Maine criteria were detected in the effluent from the Navy’s Groundwater Extraction and Treatment System (located at Brunswick Landing), and in several property-wide monitoring wells.

Since the completion of the 2014 sampling and monitoring, the Navy has continued its evaluation of PFC’s at Brunswick Landing with a field investigation in June-July 2015 of the Picnic Pond System, Merriconeag Stream, and two background ponds that included surface water, sediment, and pore water sampling. The Navy received the analytical data from this latest investigation in August 2015. Over the next several weeks, the Navy and the regulators will be validating this data.

With the exception of the golf course, all water used at Brunswick Landing comes from the BTWD. Navy tests have determined that no PFCs are present in the BTWD water supply. In compliance with the property transfer documents from the Navy, no groundwater is used anywhere on Brunswick Landing except at the golf course where pond water is used for irrigation. There is a well for the club house. While Maine DEP believes there is no requirement to do so, the Navy plans on testing the well water used at the golf course.

As with other environmental issues, the Navy continues to work closely with EPA, DEP, MRRA and the local citizens group on these types of issues as they arise. This type of partnership with the U.S. Navy and the environmental regulators has been instrumental in the effective, safe, responsible and efficient reuse of property at NAS Brunswick.

Implementing the Plans – Property Reuse

In 2007, the State Legislature established the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority (MRRA) to implement the plans at both the Brunswick and Topsham locations. Both the BLRA and TLRA ceased activities in December of 2007 and MRRA began operations on January 1, 2008. Steve Levesque was chosen to lead that organization and has retained the majority of his very talented and dedicated team to manage the redevelopment effort going forward. Most are still with the organization today.

MRRA was established by the State Legislature as a public municipal corporation and instrumentality of the State. It has an eleven member Board of Trustees, all appointed by the Governor. MRRA’s statutory mission is to implement the Reuse Master Plans for Brunswick and Topsham; manage the transition of the base properties from military to civilian uses; and create high quality jobs for the region and State. The Legislation further identified short-term, intermediate and long-term goals for the redevelopment effort:

Short-term goal: Recover civilian job losses in the primary impact community resulting from the base closure (700 jobs);

Intermediate goal: Recover economic losses and total job losses in the primary impact community resulting from the base closure ($140 million in payroll); and

Long-term goal: Facilitate the maximum redevelopment of base properties (12,000 + jobs).

The Results

At the time of this writing, it’s a little more than four years into the redevelopment of the former Naval Air Station in Brunswick, now called Brunswick Landing and the Topsham Commerce Park. The redevelopment effort has been quite successful to date and has been recognized nationally as a model for excellence in base redevelopment. In fact, the Department of Defense reports that the NAS Brunswick redevelopment effort is far ahead of all other former military bases from the 2005 Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) peer group in terms of redevelopment success; and the Association of Defense Communities has recognized MRRA with leadership awards in 2011 and 2015.

Here’s a look at the economic impact of redevelopment since the Navy left in May of 2011, just four years ago:

• Nearly 1,213 jobs have been created — about 60 percent more than projected four years into this project.

• More than $75 million in property valuation has been added to tax rolls of the Towns of Brunswick and Topsham. That value didn’t exist when the Navy was here.

• More than $2.6 million in property taxes is generated by the redevelopment effort annually. Brunswick Landing and the Topsham Commerce Park are now home to over 95 business entities, including 25 that are new to the State of Maine. Many of these businesses have international and multi-state reach.

• Over $300 million of private sector investment has occurred in both Brunswick and Topsham and we have attracted seven development companies to date. More than $50 million in state and local contracts have been awarded for various projects at Brunswick Landing and Topsham Commerce Park.

• TechPlace, Brunswick’s technology accelerator/manufacturing business incubator for start-ups, opened at the beginning of the year and already has 30 new innovative businesses with 72 employees.

• Brunswick Executive Airport, which opened April 2011 while the Navy was still here, has grown steadily to nearly 16,000 air operations (takeoffs/landings). This equates to more fuel sales, airport jobs, and more planes based here. The Town of Brunswick benefits from significant excise tax collected from owners of planes registered at BXM.

• Southern Maine Community College established its Midcoast Campus at Brunswick Landing with its world-class composites program and research lab. More than 1,000 students attend classes at SMCC and its partner tenant the University of Maine.

• MRRA has established a vision of a renewable energy center at Brunswick Landing for the generation, distribution and management of renewable energy. This campus-wide living laboratory will allow for entities to “plug-n-play” various technologies and applications into MRRA’s electric grid, which it owns and operates.

• MRRA currently purchases 100 percent renewable energy, in the form of imported wind power, for the energy needs at Brunswick Landing. This year, Village Green Ventures began operation of a 1 megawatt anaerobic digester electrical generation facility at Brunswick Landing. The digester will help the area dispose of excess organic waste and sewer sludge, which will eventually help save local ratepayers and business owners money while offering businesses at Brunswick Landing a more stable, lower cost electricity rate than they’ll find anywhere else in the region.

At the time of this publication, Brunswick Landing still has an abundant amount of building facilities available for aerospace, composites, advanced manufacturing, biotech, IT and other industries. MRRA currently owns about 1,400 acres and more than 900,000 square feet of building space, with approximately 400 additional acres and 10-15 buildings still to be conveyed by the Navy, once they receive their environmental clearances. MRRA will continue to convey property to the private sector, which spurs more activity.

MRRA works closely with the Town of Brunswick, the State of Maine and others to create and improve open space and recreational activities at Brunswick Landing. The Town recently commissioned the Kate Furbish Preserve, a 750 acre coastal forestland conveyed by the Navy. This area will be forever protected as a conservation area. MRRA and the Town recently opened several fence lines to pedestrian and bicyclists, which is the first phase of a circumferential perimeter trail system. The Town moved its recreation center to the former Navy field house. And MRRA also added about 36 additional acres of habitat for endangered bird species on airport property.

Challenges to NAS Brunswick Redevelopment

Redeveloping a former military installation is not like a typical real estate development activity. There are many challenges to these efforts that are not realized in some of other real estate transactions. Aging infrastructure, unmaintained buildings, lack of adequate financial resources and politics are all challenges that had to be dealt with on this project.

Aging Infrastructure

Because the NAS Brunswick installation has been in existence since 1943, much of its basic infrastructure, such as sewer lines, water lines, storm drainage, road systems and its electric grid are aging. While some repairs and upgrades were made to these infrastructure systems during the Navy’s ownership, by the time the systems were turned over to MRRA, they were all in fairly poor condition. This lack of deferred maintenance is literally costing MRRA millions to repair and upgrade.

The sewer system is in the worst shape, with significant inflow and infiltration occurring into the old distribution lines; with some clay pipes over 60 years old. Because of the age and poor condition of the lines, significant levels of unwanted groundwater and rain runoff get into the pipes and then into the waste water treatment facility. This issue costs MRRA significant dollars in both its sewer bill to the local sewer utility district and in costs to repair and upgrade the system.

The water and road systems also need to be upgraded to meet current standards, and the electrical grid system needs to be significantly upgraded to accommodate business growth at Brunswick Landing and support the vision of a campus-wide renewable energy center and smart grid.

Poorly Maintained Buildings

There are over 250 buildings at the two former base facilities – many are less than twenty years old, which is certainly an asset to the redevelopment effort. However, due to scarce resources at the federal level, the Navy did not have sufficient resources to adequately maintain these buildings in proper fashion. This was especially evident following the 2005 closure announcement, where property sustainment funds were shifted to other active bases in the military inventory.

The net result of this deferred and no-maintenance scenario means that MRRA must contend with failing building systems, especially heating and ventilation and roofing systems that could have been avoided with proper maintenance. In addition, while a number of buildings are fairly new, many do not meet current code requirements for handicap access and life, safety and welfare, which needed to be upgraded to accommodate new commercial uses. Also there was no individual water or electric meters on any of these properties. As one can imagine, it is costing MRRA significant financial resources to address these building issues and prepare the buildings for new occupancy.

Financial Resources

Securing the vast financial resources needed to address the infrastructure and building issues described above and supporting the administration, marketing and operations of MRRA is an ongoing challenge, involving many revenue sources. MRRA has been very aggressive and very successful in securing federal grants to help with operational costs and upgrading infrastructure and building systems. To date, it has received nearly $70 million from several agencies within the federal government to help with these costs. The State of Maine has also assisted with a $3.25 million general obligation bond to assist with building and infrastructure support and the Town of Brunswick is supporting infrastructure improvements through the use of a tax increment financing agreement with MRRA. Finally, MRRA supports its ongoing operations through revenues obtained through the lease and sale of property at the two properties

Politics

Like in most base closure situations, there were some political conflicts associated with the NAS Brunswick redevelopment effort. Political discord is one of the biggest issues that can hamper and retard redevelopment efforts. There are numerous examples across the U.S. where political conflicts have seriously delayed redevelopment efforts. Brunswick is not one of these cases. The NAS Brunswick effort has received incredible support from two State governors, the State Legislature, all of Maine’s delegation in the federal Congress, and the two towns where former base properties are located.

The biggest political issue that has arisen to date involved a dispute between the Town of Brunswick and the State regarding member representation on the Governor-appointed MRRA Board of Trustees. The enabling legislation prohibited people serving political office from serving on the Board. The Town wanted to have its Town Manager appointed, but the State (two different Governors) and the Legislature disagreed.

This decision to not appoint the Town Manager to the Board created some uncomfortable moments for MRRA in the early years in carrying out its duties. In the legislation, the towns retained taxation and zoning authority over the former base properties. Thus it was imperative that MRRA and town staffs work closely together to affect the redevelopment effort. Clearly, the Brunswick Town Manager and some members of the Town Council were bitter about this decision and made things a bit of a challenge. However, once the Town Manager person moved on, the relationship between the two parties seemed to improve significantly and currently enjoy a solid relationship.

Summary

In summary, the NAS Brunswick redevelopment project has become a very good success story in a very short time and the project is significantly outpacing the rest of its peer facilities around the country. The redevelopment effort is experiencing strong job growth and other performance metrics, which are ahead of its forecast. The Reuse Master Plan is being implemented in accordance with its redevelopment vison and growth in target industries. The new college campus at Brunswick Landing has become a significant regional workforce development asset and the executive airport is really taking off in support of general and business aviation for the Midcoast region of Maine.

With this said, there is a long-way to go before we are ready to claim success on the redevelopment project. There are still significant challenges to overcome, particularly in securing necessary resources to improve ageing infrastructure systems, airport runways and poorly maintained buildings. It is expected that it will take 20-30 years to achieve full redevelopment.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

References:

- Department of Defense (2005) “Defense Authorization and Base Closure Act of 2005, as amended, BRAC Implementation Regulations” and guidance documents.

- Department of Defense, Office of Economic Adjustment (2009) “Defense Community Profiles – Partnering for Success”.

- Department of the Navy (2006) “Environmental Conditions of Property Report for NAS Brunswick”.

- Department of the Navy (2011) “History of NAS Brunswick”, as presented at disestablishment ceremony, May 31, 2011. Maine State Planning Office (2007) “Impacts of closure of NAS Brunswick.

- Maine State Planning Office (2007) “Impacts of closure of NAS Brunswick“.

Further Reading:

- Brunswick Local Redevelopment Authority (2007) “Reuse Master Plan for NAS Brunswick”.

- Department of the Navy (2009) “Final Environmental Impact Report” NAS Brunswick Reuse Master Plan.

- Department of the Navy (2009) “Final Environmental Assessment” NAS Brunswick-Topsham Annex Reuse Master Plan

- Topsham Local Redevelopment Authority (2007) “Reuse Master Plan for NAS Brunswick-Topsham Annex”.

About the Author:

Steven Levesque is Executive Director of the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority in Brunswick, Maine.

Excerpted by permission from:

Sustainable Regeneration of Former Military Sites

(Routledge Research in Planning and Urban Design, June 2016)