This Guest Article for REVITALIZATION was written by Justin R. Wolf

“What have the highways wrought?” asks Marvin Anderson.

In the early 1960s the state of Minnesota, with funds from the Federal Aid Highway Act, built a 13-mile stretch of I-94 between Minneapolis and St. Paul.

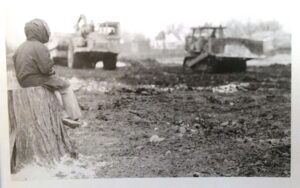

An unidentified boy observes the construction of I-94 in St. Paul, on the site where a thriving neighborhood once stood. Courtesy: ReConnect Rondo, with permission from Minnesota Historical Society.

Rather than place the highway’s path along a proposed northern route, which followed abandoned railroad tracks, the interstate went right through the predominantly Black and working-class neighborhood of Rondo, effectively cutting it in two.

Anderson, 81, is a longtime Rondo resident whose own family home was among the 700 leveled by highway construction. He is also the Board Chair and co-founder of ReConnect Rondo, the nonprofit organization leading the effort to create the state’s first ever African American cultural enterprise district, right in the middle of Rondo.

The catch is: the middle of Rondo is currently occupied by a sunken stretch of highway. “It took so much time for people to realize the damage done,” says Anderson. “And those of us who got caught up in it, we were just the collateral damage.”

America is having a reckoning with its highways. From coast to coast and throughout the heartland, there exist today dozens upon dozens of what William Fulton, Director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, calls “urban scars,” stretches of highway built more than a half-century ago that cut directly through key sections of a city’s core, often jarring whole communities of color and making mobility for anything other than speeding autos a tricky and undesirable proposition.

Construction of I-94, circa 1965. Courtesy ReConnect Rondo with permission from Minnesota Historical Society.

And while the sentiment to wage action and solve many of the chronic problems brought on by these highways isn’t new (Congress for New Urbanism has produced seven “Freeways Without Futures” reports since 2008!), the sentiment has evolved into a genuine movement, with actual funding and federal legislation in the pipeline, plus some well-deserved headlines to boot.

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 remains the largest public works project in the country’s history. It was an undertaking as ambitious in its singularity as it was flawed in its execution. When the railroads were being built, whole towns were created (and smaller ones were expanded) to capitalize on the gains that come with being located near a rail hub. (See Atlanta, Chicago, and Los Angeles.)

When the highways were built, they ravaged entire neighborhoods in those very cities. Indeed, this national reckoning deals with much more than correcting some of history’s urban planning blunders. This reckoning is over the casual criminality of eminent domain and the overwhelming loss of intergenerational equity in communities of color, and it’s about making progress on a community-wide scale that is accountable and measurable.

Thanks to the Highways to Boulevards movement and likeminded programs, we can see examples of this playing out, to varying degrees of success, in places like Oakland, Dallas, New Orleans and many other towns and cities across the country. But in the Rondo section of St. Paul, something quite different is taking place.

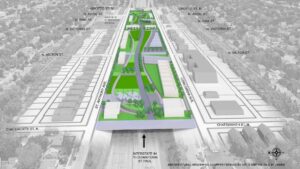

For the past 12 years ReConnect Rondo has been publicly advocating for the physical and spiritual splicing of the neighborhood’s divided halves. The reconnection in question is in the form of a proposed land bridge, a brand new 22-acre plot of land that would traverse a sunken half-mile length of I-94. As marvels of engineering go, the land bridge would be one for the books, though certainly not without local precedent (Target Field in Downtown Minneapolis is essentially built on a land bridge).

What’s more, after years of Sisyphean ebb and flow, ReConnect Rondo recently benefitted from a funding trifecta that will bring in a combined $11.5 million in federal, state and regional funds to go towards planning and predevelopment. In the grand scheme of things, this is hardly a financial tsunami (the estimated cost of the land bridge exceeds $450 million), but it’s inarguably a step in the right direction.

Rendering of proposed land bridge over I-94 spanning Chatsworth St. N to Grotto St. N, looking east towards downtown St. Paul. Courtesy ReConnect Rondo.

For his part, Anderson aspires to build something more holistic. Those who question this effort, on economic terms or otherwise, in his estimation, “are looking at the land bridge as a physical entity rather than a restorative, moral, and fundamental project. It has physical attributes and it’s bringing in land, yes … putting in 22 acres of land in the middle of the city, that’s unheard of. But the innovation we’ve committed ourselves to is so much more than the bridge.”

A bridge is one of the most accessible metaphors there is, and this fact isn’t lost on Anderson. This land bridge is the vehicle by which healing and restoration can start to occur in Rondo, and branch out from there; what it’s not, according to Anderson and many of ReConnect Rondo’s fellow stakeholders, is a reparative solution unto itself.

“Many people see affordable housing as a solution, as the end point,” says Björgvin Sævarsson, CEO of Yorth Group, who sits on ReConnect Rondo’s Technical Advisory Team. “It’s not! The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals is another example. A lot of cities and companies look at those as the end point. They’re not. In restorative development these things are merely milestones towards something bigger and more interconnected.”

“Rondo will be a coalition of people, of public and private philanthropy,” says Anderson, “a composite of the very best of 21st-century thought. It will take something that’s not there now and create a model that other communities can use.”

In the most literal sense, what’s not there now is land. The model that Anderson is referring to would be a parcel of land built using the principles of restorative development (a term coined by Storm Cunningham in his 2002 book, The Restoration Economy).

Marvin Anderson (left) at the Healing Ceremony for the groundbreaking of Rondo Commemorative Plaza, the nation’s only memorial park dedicated to the destruction of a community due to highway construction. Courtesy ReConnect Rondo.

Anderson makes frequent use of the word “restore” and its many derivations. In doing so he is channeling the profound importance of restoring what was lost rather than simply replacing what was razed. He’s also speaking directly to the community-led and, more so, community-owned nature of the development.

ReConnect Rondo intends to create a community land trust that would not only ensure the stability of rents and property taxes, but also provide pathways for descendants of Rondo to obtain loans, own their own homes and businesses, and elect trustees of the land. This trust would also help stem the tide of gentrification and speculation that inevitably follows the redevelopment – or in this case, wholesale development – of urban areas.

In realizing this community-centered vision, Anderson, along with Executive Director Keith Baker, forged partnerships with companies that possessed the tools to engage with the public as well as the capacity to process that feedback into usable data.

“When we started to work with ReConnect Rondo, the land bridge concept was there but we didn’t know just how big it was going to be,” says Jonathan Bartling, Digital Practice Director at HGA, an architecture and engineering firm based in Minneapolis.

HGA was brought onto the project in 2018 to work with Rondo and guide community members first-hand in the planning and visualization of the land bridge. A big part of the firm’s approach involved developing customized Augmented Reality (AR) tools, wherein members of the community could interact with these tools on a tablet or smartphone and, according to Bartling, have “the ability to inform and direct and guide what this restorative project was going to look like, how it was going to be laid out, how it was going to heal.”

Bartling made certain to point out that, at the end of the day, his firm’s AR tools were built with the intention of “understanding people, not spaces” and to “democratize the design process,” rather than proscribe built solutions to a problem that isn’t fully understood.

Had Bartling and his team taken a more traditional approach with Rondo, architecturally speaking, this might have involved delivering a PowerPoint littered with anecdotal talking points and sobering statistics about what the neighborhood lost (which Anderson already knows forwards and backwards), accompanied by an Uncanny Valley’s worth of artist renderings depicting some new-and-improved Rondo rife with glassy mid-rises and bicyclists humming along tree-lined boulevards.

Bartling stressed that this was not the case: “At traditional community engagement meetings, they’re led by a facilitator and then a bunch of people sitting around just watching. We wanted to turn that on its head and have the community members be the ones facilitating and talking and ideating, with us capturing all of that information and data.”

As would be expected from such an exercise with the general public, much of the data gathered by HGA was informed by ideals and a sense of history, not necessarily principles grounded in urban planning, which was very much the point. “At the end of the day, the common theme was all about connection, it was about healing,” he added.

Video still of proposed land bridge. Courtesy HGA (Full video and additional info available at https://hga.com/reconnect-rondo-seeks-community-feedback/).

The Rondo neighborhood was once the proverbial backbone of St. Paul’s Black community. In addition to being the home of 80% of the city’s Black population, Rondo laid claim to the St. Paul chapters of both the NAACP and Urban League and was home to at least four Black-owned newspapers, including the Minnesota-Spokesman Recorder, the longest-operating Black-owned business in the state.

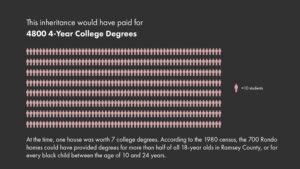

Rondo had a thriving business community, religious centers and social clubs. As the one-time home of Roy Wilkins, it was a nucleus of the Civil Rights movement. When I-94 came through, it displaced 61% of Rondo’s residents and 48% of the neighborhood’s approximately 3,000 homeowners. Seven-hundred homes were destroyed, 300 businesses wiped out, and an estimated $158 million in home equity value was lost forever.

Taken by themselves, these numbers paint a stark picture of a state-sanctioned crime having been committed, to say nothing of the approximately 1,200 other towns and neighborhoods in the U.S. whose lower tax bases made them expendable in the greater campaign to connect the country via highways.

The mandate to restore a whole community that was literally cut in half in such a drastic way feels nothing less than extraordinarily complex. According to Sævarsson, “We’re not investing in a bridge or physical infrastructure. We’re investing in the community.”

Sævarsson’s firm, the Yorth Group, consults cities and businesses on implementing circular design and restorative development models to scale.

He’s also quick to point out that buzz phrases like sustainable development, carbon neutrality, circular economies and the like essentially solve nothing if they exist in silos, disconnected from the operational whole.

“Restorative development looks for the value in everything,” he says. In his line of work, Sævarsson ensures that this “everything” includes a detailed understanding of a community’s history, the economic path it took, and what might have been.

“After the 1970s we changed in America,” says Sævarsson, “and we started following an economic path that made poverty more expensive. Progress in economic terms happened in pockets, and other pockets were left behind. So being poor became more and more expensive, and we began to lose equity from underneath our feet. We were creating a profit while losing equity. That was not measured. This happened in America, and it happened at an extreme scale in Rondo.”

Another word that came up often in my conversation with Anderson was “laboratory.” “Rondo can act as a laboratory for 21st-century building,” he remarked.

As with any controlled experiment in a lab, all the variants rely on each other to achieve a desired result. One rogue or underperforming variant can bring the whole thing crashing down, while the isolated success of one variant can mean nothing to the larger experiment.

“We’re good at creating master plans,” Sævarsson reminds me, “but not restorative master plans. Sometimes we zoom in to solve smaller problems when what we should be doing is zooming out. When we zoom out, we can solve multiple problems at the same time.”

And therein lies the heart and soul of Anderson’s vision, a Rondo that is successful on every conceivable scale, however small or large, interdependent and synchronized, community-owned and -operated – a true urban gestalt.

Once I gained a clearer understanding of ReConnect Rondo’s broader intent and the immeasurable amount of work that Anderson had put into his community to date, I immediately felt sorry for all those times over the years he’s worked to convince cynics that something as relatively simple as a land bridge in one part of town is a city-wide investment, a means to something greater and not the end goal in and of itself.

“This vision is real,” says Sævarsson. “It’s technically feasible and it’s financially feasible. People may not understand the full value of it now, but in a couple of years they will see the true potential.”

Considering my conversation with Anderson, it became immediately apparent that the subject of Sævarsson’s remark was Rondo itself and not a plot of land over the highway.

“Our desire is to create opportunities for people to think on another level,” says Anderson, “to go higher in their aspirations, to bring together the best minds so that this little 22-acre development not only preserves and perpetuates the memory of Rondo, but it builds on that and says, ‘never again.’”

About the Author:

Justin R. Wolf is a Minneapolis-based writer and communications specialist with a learned passion for urban design, architecture, sustainability, the fine arts, and just about any discipline that is committed to improving the public realm and creating more equity in our built environment.

Justin R. Wolf is a Minneapolis-based writer and communications specialist with a learned passion for urban design, architecture, sustainability, the fine arts, and just about any discipline that is committed to improving the public realm and creating more equity in our built environment.

For more than ten years he has worked within the AEC industry, providing both in-house integrated communications and freelance writing services. Justin actively partners with internationally renowned design firms to craft stories told through the lens of sustainable development, smart growth, resiliency, community engagement, social & economic equity, environmental justice, and design innovation.

He holds an M.A. from The New School for Social Research in New York City. Justin is a regular contributor to the Common Edge Collaborative. To learn more, visit his website at www.justinrwolf.com.