Housing preferences among Americans of all ages are shifting and changing, and a growing number of individuals are seeking walkable communities. Whether it’s Millennials shying away from single-family, suburban neighborhoods or Baby Boomers seeking to downsize, small cities are seeing a resurgence as these preferences create a shift in demand.

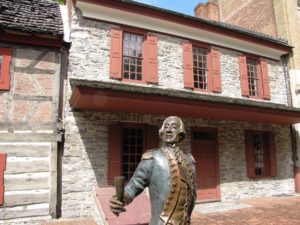

In York, Pennsylvania, a city of about 44,000 residents tucked 50 miles north of Baltimore and 100 miles west of Philadelphia, more than $319 million has been spent on development projects in the past 10 years.

But a Residential Market Feasibility Analysis conducted in 2015 shows an unmet demand for an additional 100-plus units in the six-by-six-block Central Business District alone.

Why are Millennials and Boomers choosing small cities? Why York? Our downtown area — specifically our Central Business District — has a healthy mix of retail, restaurants, entertainment and services. Young singles and couples with moderate income are looking to live within walking distance of these amenities and even their workplace. We’ve also seen a growing interest among Millennials seeking opportunities for social impact and community involvement, which are ample in our community of “creatives.” Meanwhile, older adults looking to “age in place” are seeking communities where they can be near friends, family support and services.

York’s roots are in industry: Steam engines, railroad manufacturing, automobiles and papermaking were all housed in large factory spaces. Nationally recognized names such as York International air conditioning and the York Peppermint Patty were born here.

During World War II, “The York Plan” became the national standard for manufacturing techniques. In the mid- and early 1900s, downtown thrived with department stores such as Bear’s, Woolworth’s, Wiest’s, the Bon-Ton and others that fled to the suburbs in the 1960s.

Fast-forward to today, when these large, vacant spaces are ripe for creative adaptation as developers and economic development officials seek to meet the demand for increased housing. By taking a look at three projects in various stages, we can better understand best practices for the future.

Keystone Colorworks

Located in the city’s Northwest Triangle — long a challenge for economic development officials — is a manufacturing building that had housed a railcar factory, farm equipment and wallpaper color production since its construction in 1873.

Distinct Companies — a development team that had just finished renovating a former car dealership, electrical supply house and storage facility into 25 luxury loft-style apartments north of the city — purchased the Keystone Colorworks property from the Redevelopment Authority of the City of York in 2014.

On the eve of the project’s ribbon-cutting, developer Seth Predix told the Central Penn Business Journal their investment in the project was just “basic economics.”

“Common-sense investing tells you to invest your money where other people are investing theirs, and there’s going to be a lot of money invested in downtown York over the next five years,” Predix was quoted as saying.

Keystone Colorworks has long served as a symbol of York’s challenges — how do we redevelop existing structures in a way that leverages their industrial character to meet the demand among audiences? To see a developer enthusiastically tackle a project like this — and to see all 29 apartments rented almost immediately after they came on the market — encourages everyone to think about the takeaways.

For one, developers need an honest understanding of the market: Reconfiguring over-sized commercial or manufacturing spaces to better align with current market demands provides a viable option to develop buildings that would otherwise remain vacant.

But an understanding of market demands includes the desires of your target audience — millennials drawn to an urban, walkable environment are often equally excited by the industrial finishes so readily available in our buildings. By respecting the architecture, developers can leverage this to create unique spaces that meet or even exceed the expectations of consumers.

One West

While renovations were underway at Keystone Colorworks, a similar project was taking shape directly on the city’s square: One West.

Seven connected buildings, one the former home of Bear’s Department Store from 1888 through the 1960s, had mostly sat vacant in recent years and presented a similar challenge as Keystone Colorworks: Knowing that a major department store isn’t likely to come knocking any time soon to occupy a 140,000-square-foot space in a third-class city, how do you adapt a property for reuse that fits the demands of the current market?

In 2015, the investors group One West LLC purchased the building to create a mixed-use space for retail, dining, office space and residential units. At the helm was David Yohn of Yohn Property Management, a real estate developer with a track record for renovating older buildings in the York area. Fast forward one year, and all completed units — 38 total — are fully leased, ranging from $650 a month for a 550-square-foot studio apartment to $1,500 for a 1,700-square-foot, two-bedroom unit. A locally owned bank consolidated its two downtown branches into the space in December, and a bistro restaurant is slated to open this fall. By spring 2017, another 12 residential units will be completed.

By dividing the larger space into manageable units for retail, office and residential needs, a space formerly overwhelming in scale can become usable and even desirable from a multitude of perspectives.

Similar to other adaptive reuse projects we’ve seen, developers have maintained much of the building’s original character: Beautiful facades, large windows, stained glass and unique spaces make the project appealing to today’s tenants.

Revi Flats

Just one block west, a four-building, $14 million renovation effort is underway in an equally challenging revitalization project. Formerly known as “Department Store Row,” the unit block of West Market Street is undergoing large-scale revitalization lead by Royal Square Development and Construction, which received an $8.75 million tax credit allocation among other private and public support.

Several of the buildings had sat vacant, including the 15,000-square-foot former Woolworth’s building that the City Redevelopment Authority acquired in the late 1990s.

Creative solutions to finance a project of this nature were key in pushing forward — including RSDC’s pursuit of the federal funding in New Market Tax Credits, allocated through a regional economic development organization that provides loan capital to real estate developers and businesses. By early 2017, an additional 36 market-rate apartments known as Revi Flats will be available to meet the demand among renters.

Additional retail spaces — one of which is already occupied by a 10,000-square-foot arcade for all ages that focuses on both retro and current games — will add to the nearby amenities for residents.

What does it mean for small cities?

Adaptive reuse, creative funding and bold action. It’s working in York despite outside challenges — similar to other small cities and municipalities in Pennsylvania, York must find a way to flourish and grow in spite of laws from a state level that can often hinder progress.

But, leadership in York is confident that we can drive our city forward — and set an example for others seeking to revitalize areas through adaptive reuse — by keeping a few main points in mind:

- Understand your market: The Residential Market Feasibility Analysis conducted in 2015 demonstrated a clear demand for residential units. By providing this study to developers seeking to invest in the area, economic development officials are able to better demonstrate the promising opportunities for investment. In York, we also know that retailers aren’t often seeking 100,000-square-foot spaces. Instead, we need to work with business owners to understand their needs, and partner with them to find a space that fits.

- Get creative with funding: The Market Street Revitalization Project may never have happened without the combination of private and public investment, including the allocated tax credits. By seeking creative solutions to funding needs, projects that have longed seemed overwhelming in scale can become manageable.

- Respect the architecture: If York wanted to simply build 100 new market-rate apartments, it could build them. But our community recognizes the history and the heritage in many of these old spaces. Perhaps even more important, community leaders recognize that the path to revitalizing our downtown area starts by paying attention to some of our larger challenges — a now-empty Department Store Row, or a parcel of undeveloped land in the Northwest Triangle. By adapting these spaces to fit current needs, and respecting the architecture in the process, we’re able to create a product that entices further investment in our city.

- See the bigger picture: In 2008, The City of York instituted the ReTAP program (Residential Tax Abatement Program), which allows developers to request property-tax immunity for 10 years on the increase of assessed value. In most cases, developers will say that “the numbers just don’t work” for redevelopment projects. The back-end assistance of reduced or gradually increasing property tax rates will help with the project’s pro forma. Cities must recognize that delayed property tax revenue can be offset by secondary and tertiary induced economic development spending as well as personal income taxes gained by new residents.

- Build the buzz: Urban areas often have image problems that are propagated by local news reports about crime, taxes and parking challenges. Consistent positive messages about the Central Business District that are spread by local “cheerleaders” not connected with municipal government are critical to building a sense of pride and confidence that investors/developers want to belong to. By using social media outlets like Facebook and Twitter and by being proactive about promoting positive news, a community can change the tone about city life and can, in some cases, even turn the tone of the local newspaper’s reporting.

By being knowledgeable about demands, making the numbers work, and creating excitement and “good vibes” about your small city, you can leverage existing spaces to create a resurgence of authentic, vibrant, walkable communities.

About the Author:

Blanda Nace is Vice President of Community Affairs for the

Blanda Nace is Vice President of Community Affairs for the

York County Economic Alliance, which is the York County

Chamber of Commerce and Economic Development Corporation.