In yet another tale of aquaculture-based ecological disaster, Pacific oysters escaped in the early 1990s from farms off the coast of Germany. They quickly established feral populations along the North Sea’s eastern shores.

The oysters were invasive, spreading without restriction, and smothered native mussels, which are an important bottom-of-the-food-chain food source for the region’s seabirds. Ecological catastrophe appeared imminent.

Yet that’s not what happened. Twenty-six years after their arrival, Pacific oysters and mussels now seem to be coexisting. The resulting communities might even be healthier than the mussels alone.

“The introduction and spread of Pacific oysters has entailed more resistant, more resilient and more diverse communities at sites of the former mussel beds,” said Karsten Reise, the study’s lead author and an ecologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research. “Oyssel reefs are likely to better cope with the challenges of the Anthropocene.”

During the invasion’s early stages, mussel beds made inviting anchor points for larval oysters. It didn’t take long for those beds to be lost beneath a carpet of big, fast-growing invaders. Hence the alarm.

Yet as Reise’s team observed, subsequent generations of oysters grew preferentially on earlier oysters, and new generations of mussels settled undisturbed in the spaces between them.

This, of course, is an unusual situation, and shouldn’t be taken as an excuse to not fight human-introduced invasive species, and certainly not to continue operating the disastrous fin fish farms (like salmon) that are devastating wild populations via diseases, pollution, and genetic contamination.

Abstract from study:

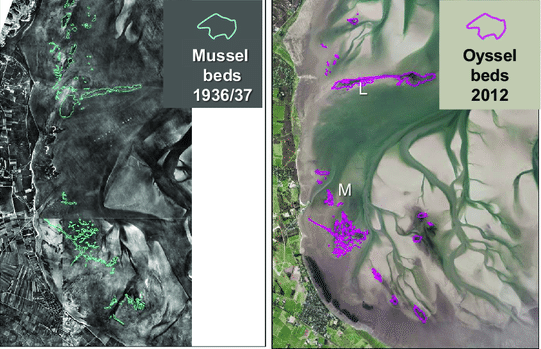

Unintended species introductions may offer valuable insights into the functioning of species assemblages. A spectacular invasion of introduced Pacific oysters Magallana (formerly Crassostrea) gigas in the northern Wadden Sea (eastern North Sea, NE Atlantic) has relegated resident mussels Mytilus edulis on their beds to subtenant status. At the beginning of feral oyster establishment, mussel beds offered suitable sites with ample substrate to settle upon.

After larval attachment to mussels, the fast-growing M. gigas overtopped and smothered their basibionts. With increasing Pacific oyster abundance and size, oyster larvae preferentially settled upon oysters, and the ecological impact of the invaders on the residents changed from competitive displacement to accommodation of mussels underneath a canopy of oysters. Oysters took the best feeding positions while mussels received shelter from predation and detrimental epibionts.

The resident’s mono-dominance has turned into co-dominance with an alien, persisting in novel, multi-layered mixed reefs of oysters with mussels, which we term “oyssel reefs.” The first 26 yr of the Pacific oyster’s conquest of mussel beds in the northern Wadden Sea may question the overcome notions of natural balance, superiority of pristine over novel species combinations, and of introduced alien species threatening biodiversity and ecosystem stability in general.