The 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, which the West celebrated as a triumph, had been devastating for many Muscovites. Teachers and workers in government-owned factories were unpaid for months, and the middle class went hungry.

By the late ’90s life had become less dire, but there were two currencies circulating, the second issued to deal with the hyperinflation of the first, and city services had collapsed. The parks were full of garbage and alcoholics, the playgrounds were carpeted with broken glass and smelled of urine, and the lovely old metro stations were encrusted with kiosks. There wasn’t even snow removal.

Moscow, the country’s capital and the place where its large corporations and oligarchs are based and pay taxes, is now visibly prosperous. According to the Brookings Institution, it has the 10th-largest economy among global metro areas, based on gross domestic product.

By all accounts, the driving force behind the city’s reinvention is Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin.

Sir Roderic Lyne, the British ambassador to Moscow from 2000 to 2004, says: “If we’re just simply talking about the built environment, this is the greatest transformation I’ve observed.” He says “some of the buildings put up under Luzhkov were of a Trumpian grandiloquence and vulgarity. I’m not personalizing it in Mr. Sobyanin, but I think the taste has improved with the change of mayor, and Moscow has become a very livable, modern city.”

Moscow is putting its focus on “competing globally by designing locally.” It’s reverse-engineering downtown areas to prioritize pedestrians over cars and greening block by block in what’s called the My Street program. Sidewalks are being widened, city trees are being replanted, and bicycles are proliferating.

Moscow spends 15 percent of its total budget on improving the transportation mix, which primarily means making the city less automobile-friendly. It has instituted congestion pricing, and added a ring road to better-connect the outlying neighborhoods.

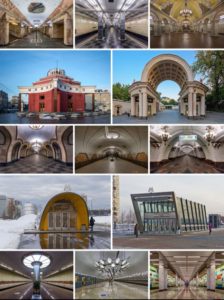

Maybe most important, they created the popular Moscow Central Circle, an above-ground, 54-kilometer light-rail train connecting outlying neighborhoods to each other, and the existing metro stations, which are being cleaned-up and renovated. The metro’s total capacity is up 30 percent since 2013 and is expected to double between now and 2021.

As of 2017, the Moscow Metro, excluding the Moscow Central Circle and Moscow Monorail, has 206 stations and its route length is 339.1 km (210.7 mi), making it the fifth longest in the world. The system is mostly underground, with the deepest section 84 metres (276 ft) underground at the Park Pobedy station, one of the world’s deepest.

The usual issues of painful–often ujust—displacement aside, today’s Moscow is clean, green, and inviting…at least in the areas that aren’t currently undergoing zealous work to repurpose, renew, and reconnect them (the popular 3Re strategy).

As with most revitalizing cities around the world, affordable housing in Moscow is less of a success story.

The city tried to demolish–rather than renovate—a huge swath of Cold War-era apartments, but residents objected. This was largely because beautiful old trees had beautified the neighborhood over the past 60 years, and because of the rich human connections that had been formed.

The Renaissance Moscow Towers are scheduled to open in 2019. Rendering courtesy of Renaissance Development.

Now some 7900 Khrushchevka blocks in Moscow are slated to be torn down, in what will be one of the largest urban resettlement programs in history. With the backing of the president, Vladimir Putin, Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin has declared the programme an “absolute necessity” to replace ageing housing. He promised the replacement flats would be 20% larger on average.

To many locals, it is just another example of profit taking precedent over heritage.

“This is the first housing block that Khrushchev built. They don’t have any regard for this now,” machinist Yevgeny Rudakov said of his home. “Money comes before anything else.” He added that he didn’t “know why Putin said” to tear such flat blocks down. “The building is good, the walls are thick.”

It’s not just housing heritage that’s being demolished. Many preservationists say that that Sobyanin is destroying Moscow. Over 159 historic sites—many of them designed by renowned architects—have been demolished during Sobyanin’s administration. These include old railroad stations, the estates of Russian nobility, and even Moscow’s historic 1904 mosque.

To those who value heritage, Moscow’s impressive progress has been excruciatingly painful.

Featured image is a new Moscow theme park. Image courtesy of Nagatino_Architecture.

See full Bloomberg article by Valerie Stivers about the transformation.

See Guardian article by Alec Luhn about the residential demolitions.