Owens Lake is a mostly dry lake in the Owens Valley on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada mountains in Inyo County, California. It’s about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Lone Pine, California.

Unlike most dry lakes in the Basin and Range Province that have been dry for thousands of years, Owens held significant water until 1924, when much of the Owens River was diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct, causing Owens Lake to desiccate. Before the diversion of the Owens River, Owens Lake was up to 12 miles (19 km) long and 8 miles (13 km) wide, covering an area of up to 108 square miles (280 km2).

Today, some of the flow of the river has been restored, and the lake now contains some water. Nevertheless, in 2013, it is the largest single source of dust pollution in the United States. How did this tragedy happen?

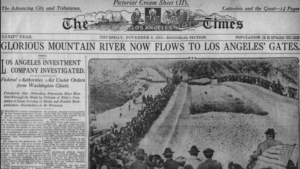

A century ago, agents from Los Angeles converged on the Owens Valley on a secret mission. They figured out who owned water rights in the lush valley and began quietly purchasing land, posing as ranchers and farmers.

Soon, residents of the Eastern Sierra realized much of the water rights were now owned by Los Angeles interests. L.A. proceeded to drain the valley, taking the water via a great aqueduct to fuel the metropolis’ explosive growth.

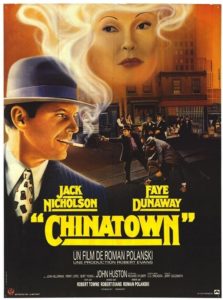

This scheme became an essential piece of California history and the subject of the classic 1974 film “Chinatown.” In the Owens Valley, it is still known as the original sin that sparked decades of hatred for Los Angeles as the valley dried up and ranchers and farmers struggled to make a living.

This scheme became an essential piece of California history and the subject of the classic 1974 film “Chinatown.” In the Owens Valley, it is still known as the original sin that sparked decades of hatred for Los Angeles as the valley dried up and ranchers and farmers struggled to make a living.

But now, the Owens Valley is trying to rectify this dark moment in its history. Officials have launched eminent domain proceedings in an effort to take property acquired by Los Angeles in the early 1900s.

The move comes after years of efforts by Los Angeles to make amends for taking the region’s land and water.

In 2013, for instance, the city agreed to fast-track measures to control toxic dust storms that have blown across the eastern Sierra Nevada mountains since L.A. opened the aqueduct a century ago that drained Owens Lake.

The DWP has spent more than $1 billion to comply with a 1997 agreement with the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District to combat the powder-fine dust from the dry 110-square-mile Owens Lake bed.

“The county would obviously like more economic opportunities,” said Marty Adams, chief operating officer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP) which owns the crucial properties, “and we support that.”Some officials are already raising the possibility of mounting crowdfunding purchase land from DWP land for public benefit.

Separately, after decades of political bickering and a bruising court fight, the DWP directed water back into a 62-mile-long stretch of the Lower Owens River that had been left essentially dry after its flows of Sierra snowmelt were diverted to the Los Angeles Aqueduct. But they refused to restore the ecology by removing thick stands of invasive giant reeds that have choked the renewed river.

Feature photo of Owens Lake dust storm via a href=”https://www.lonepinefilmhistorymuseum.org” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener”>Lone Pine Film History Museum