Yansui Liu is a professor and director of the Center for Regional Agriculture and Rural Development at the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR) at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS); and a professor in the Faculty of Geographical Science, Beijing Normal University in Beijing, China.

Yuheng Li is an associate professor at the IGSNRR, CAS; and office director of the Center for Assessment and Research on Targeted Poverty Alleviation at CAS. On August 17, 2017, they reported in the journal, Nature, on their 10 years of research into rural revitalization and agricultural lands restoration.

Before and after watershed restoration and regenerative agriculture in China’s Loess Plateau. Image courtesy of Arne Næss Project.

For the past decade, the two have been studying how land issues can be harnessed to improve rural lives and economies in China3 (see ‘China’s challenge’). For example, projects to restore soil fertility, increase flood resilience, and boost agricultural yields and incomes in the western Loess Plateau areas of China.

Their research, as well as work by others, suggests that it’s possible to rebuild rural villages and towns by renovating infrastructure, redeveloping local resources, and cultivating tourism, value-added agricultural products, and crafts.

They feel that policymakers and researchers must shift their revitalization efforts towards rural areas, rebalancing policies that are biased towards cities.

Rural areas in China are being abandoned for reasons that include mobility and technology, poverty, biased policy and depleted soils cause by inadequate land management.

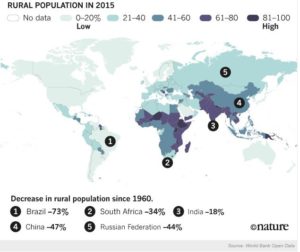

This mirrors the eighteenth century rural migration to cities that occurred in Europe during the Industrial Revolution, which saw villages shrivel as towns and cities became packed. That same trend of rural depopulation spread to North America in the twentieth century, particularly after the Second World War.

Today, in lesser-development nations, millions of subsistence farmers seek work in cities such as Delhi and Lagos in Nigeria each year, as climate change and agribusiness drive livelihoods to the brink. When rural populations wither, villages see labour shortages, recession and social degradation. Local markets shrink and workshops and small businesses close.

Today, in lesser-development nations, millions of subsistence farmers seek work in cities such as Delhi and Lagos in Nigeria each year, as climate change and agribusiness drive livelihoods to the brink. When rural populations wither, villages see labour shortages, recession and social degradation. Local markets shrink and workshops and small businesses close.

But not all countries have been ignoring rural needs. Some even have pro-rural policies. From the 1950s, Taiwan and South Korea redistributed land from the state and landlords to peasant farmers and reduced land rents to promote agricultural development. Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand invested in public health and education for the rural poor, improving life expectancy and infant survival rates. But such top-down efforts–such as providing economic incentives to people and companies to move to rural areas—often have limited success.

Engaging locals is key to success. Bottom-up initiatives act as “social glue”, encouraging people to work together. For example, in 2012, the Xiaoguan village committee in China’s northern Hebei province set up a share-based cooperative for breeding sheep and cultivating vegetables. Participants pooled money, land, labourers and machinery. In just five years, the two businesses increased residents’ per capita net income by 200%.

Sichuan pepper shrubs reduce erosion on slopes while boosting incomes in Linxia City, Gansu.

Photo credit: Vmenkov via Wikipedia.

The dry Loess Plateau of China’s Shaanxi and Shanxi provinces, also known as the Huangtu Plateau, is a 640,000 km² plateau located around the Wei River valley and the southern half of the Ordos Loop of the Yellow River in central China. It extends into parts of Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia.

The Loess Plateau was enormously important to Chinese history, as it formed the cradle of Chinese civilization and its eroded silt is responsible for the great fertility of the North China Plain, along with the repeated and massively destructive floods of the Yellow River. Its soil has been called “most highly erodible… on earth” and restoration efforts there have been a major focus of modern Chinese agriculture.

Their landscape redesign and watershed restoration work has now expanded and revitalized farms throughout the valleys near Yan’an city. The gullies of Yan’an now produce three times more maize (corn) than on the hilltops, and five times that on the slopes. Silage made from maize straw and grass is fed to cows and sheep.

Two projects set out to restore China’s heavily degraded Loess Plateau through one of the world’s largest erosion control programs with the goal of returning this poor part of China to an area of sustainable agricultural production.

More than 2.5 million people in four of China’s poorest provinces – Shanxi, Shaanxi and Gansu, as well as the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region – have been lifted out of poverty via Loess Plateau restoration.

Through the introduction of regenerative farming practices, farmers’ incomes doubled, employment diversified, and the degraded environment was revitalized:

- Incomes doubled: People in project households saw their incomes grow from about US$70 per year per person to about US$200 through agricultural productivity enhancement and diversification.

- Natural resources were protected: Uncontrolled grazing, subsistence farming, fuel wood gathering and cultivation of crops on slopes had left huge areas of the Plateau devastated. The project encouraged natural regeneration of grasslands, tree and shrub cover on previously cultivated slope-lands. Replanting and bans on grazing allowed the perennial vegetation cover to increase from 17 to 34 percent.

- Sedimentation of waterways was dramatically reduced: The flow of sediment from the Plateau into the Yellow River has been reduced by more than 100 million tons each year. Better sediment control has reduced the risks of flooding with a network of small dams helping store water for towns and for agriculture when rainfall is low.

- Employment rates increased: More efficient crop production on terraces and the diversification of agriculture and livestock production have brought about new on-farm and off-farm employment. During the second project period, the employment rate increased from 70 percent to 87 percent. Opportunities for women to work have increased significantly.

- Food supplies were secured: Before the project, frequent droughts caused crops cultivated on slopes to fail, sometimes requiring the government to provide emergency food aid. Terracing not only increased average yields, but also significantly lowered their variability. Agricultural production has changed from generating a narrow range of food and low-value grain commodities to high-value products. During the second project period, per capita grain output increased from 365 kg to 591 kg per year.

- The project significantly contributed to the restructuring of the agricultural sector, the adjustment to a market-oriented economic environment and created conditions for sustainable soil and water conservation.

- Even in the lifetime of the project, the ecological balance was restored in a vast area considered by many to be beyond help.

- Terracing required the development of roads that facilitated the access of vehicles and farm equipment and labor to these areas. Sediment control and capture transformed previously unproductive land into valuable cropping areas, helped increase water storage for communities and agricultural use and reduced flood risk. Terraces have reduced labor inputs and allowed farmers to pursue new income-earning activities.

The World Bank and their fund for low-income countries, International Development Association (IDA), helped greatly with these efforts. In the first Loess Plateau project: out of US$252 million (actual project costs), IDA contributed US$149 million; government/counterpart funding US$103 million. In the second Loess Plateau project: IDA contributed US$50 million; IBRD US$99 million; and government/counterpart funding US$90 million. (China was still eligible for credits from the International Development Association, the World Bank’s fund for low-income countries, when the projects were approved.)

The physical and economic transformation of the Loess Plateau offers the clearest demonstration of what can be achieved through close partnership with the government, good policies, technical support and active consultation and participation of the people. IDA resources – through direct investments, policy and technical assistance, training, capacity building and the efforts and behavioral change of the people in the project area – helped demonstrate the effectiveness of a model that improved the lives and livelihoods of more than 2.5 million people, and many more through replication.

But a scientific plan is needed to guide the revitalizing process. Researchers must understand the forces that drive rural decline and rural responses to globalization and climate change. Big-data analyses and simulations are required for monitoring rural development. And the effectiveness of different forms of land consolidation needs to be understood.

Featured photo of the Loess Plateau by Till Niermann via Wikipedia.