In just under two years of intensive ecological restoration, conservationists redirected two extinction-bound Chilean seabirds toward recovery.

Chile’s National Forestry Corporation (CONAF) and Island Conservation successfully removed the introduced, damaging (invasive) European rabbit population that was destroying native vegetation and fragile nesting habitat for the IUCN Vulnerable Humboldt Penguin and IUCN Endangered Peruvian Diving-petrel on two islands of the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve.

Chile’s National Forestry Corporation (CONAF) and Island Conservation successfully removed the introduced, damaging (invasive) European rabbit population that was destroying native vegetation and fragile nesting habitat for the IUCN Vulnerable Humboldt Penguin and IUCN Endangered Peruvian Diving-petrel on two islands of the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve.

“The return of these islands to the conditions needed to support seabird nesting not only stands to prevent the extinction of the Vulnerable Humboldt Penguin and Endangered Peruvian Diving-petrel, but also supports Chile’s biodiversity goals and builds momentum in the movement toward global environmental health, as well as improving eco-tourism opportunities for local communities,” says Aarón Cavieres, executive director at CONAF.

This marks the first protected area of its kind within the Chilean Protected Areas Network (SNASPE) to be declared free of invasive vertebrate pest species, an achievement that benefits native wildlife and the eco-tourism industry centered around them.

The islands of Choros, Damas, and Chañaral, which make up the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve, bathe in the productive, nutrient-rich waters of the Humboldt Current System. They are home to 80% of the world’s Vulnerable Humboldt Penguin (Spheniscus humboldti) population and were once home to 100,000 pairs of Endangered Peruvian Diving-petrel (Pelecanoides garnotii).

“The reserve is a cornerstone of a growing eco-tourism industry built by nearby fishing communities,” says Cavieres. “Eco-tourism, driven by the unique wildlife of the Humboldt Current System, offers a sustainable future for the region’s native plant and animal species as well as the local communities.”

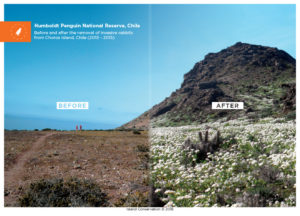

For millennia, the region’s seabirds and sensitive desert plants thrived together, but everything changed early in the 20th century when the European Rabbit was introduced to Choros and Chañaral islands. Invasive rabbits denuded the islands of shrubs and delicate herbaceous plants, occupied diving-petrel nests, and ate the cactus species that provided shaded nest sites for penguin chicks. In addition to the many threats these seabird species face at sea, the loss of breeding habitat put these birds at risk of extinction and threatened to compromise a budding eco-tourism industry centered around seabird and marine mammal observation.

In 2013, CONAF, in collaboration with Island Conservation, took the first step toward meaningful intervention in the Reserve. To restore the conditions needed to support native species and the eco-tourism industry built around them, the partners removed invasive rabbits from Choros Island and declared the project a success one year later in 2014.

Island Conservation Project Manager Madeleine Pott commented, “The results of the restoration on Choros Island were almost immediately evident across the island. We saw fields of seedlings, hillsides covered in the threatened flower Alstroemeria philippii, and Peruvian Diving-petrels looking to nest in burrows that had been taken over by rabbits.”

An important element for the successful confirmation of the project was the participation of a trained dog in the detection of invasive rabbits. Finn is a Labrador Retriever, trained in New Zealand, who has contributed to several conservation projects around the world. Finn played an important role in confirming the successful removal of invasive rabbits from Choros Island.

The success on Choros paved the way for a similar intervention in 2016 on Chañaral Island, which is two-thirds bigger than Choros. A team of 30 people conducted fieldwork over a 20-month period, covering over 6,680 kilometers; they braved the harsh desert sun and the powerful southern winds that rip up from the Antarctic to complete the project.

After months of monitoring Chañaral for signs of remaining rabbits, the island and the entire reserve—the first protected area of its kind within the Chilean Protected Areas Network (SNASPE)—have been declared free of invasive vertebrate pest species. Scientists have already spotted signs of a healthy ecosystem resurging: barren landscapes have been replaced by fields of flowers and 16 species of plants never before recorded on the island have been identified – including three species never seen before in the Reserve.

As native plant and wildlife populations bounce back, the nearby fishing communities look forward to increased eco-tourism opportunities, which center on the vibrant marine and terrestrial communities of the Reserve.

Choros Island Restoration Project partners on Choros Island, Chile. Photo by: Tommy Hall / Island Conservation

“The rebounding vegetation and wildlife of Choros and Chañaral demonstrate the power of invasive species removal,” says Pott. “The restoration of the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve offers hope for continued conservation success in the region and around the world. CONAF’s commitment to protecting native Chilean species positions them to achieve AICHI biodiversity targets, specifically targets 5, 9, and 12.”

Building on this success, CONAF and Island Conservation are looking to restore other islands in Chile with high biodiversity benefits, including Alejandro Selkirk Island in the Juan Fernández Archipelago.

Featured photo, courtesy of Island Conservation, is of Humboldt Penguins on Chañaral Island, Chile.