On February 1, 2022, three institutes that are working to restore forest health and build resilience by reducing catastrophic wildfires in the U.S. West are getting a $20 million financial boost from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by the U.S. Congress in November of 2021.

The funds will go to the Southwest Ecological Restoration Institutes (SWERI), which comprises the New Mexico Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute (NMFWRI) at Highlands University, the Ecological Restoration Institute at Northern Arizona University, and the Colorado Forest Restoration Institute at Colorado State University.

The funding will help expand a vegetation treatment database nationwide and measure the effectiveness of forest treatments.

The funding SWERI will receive is a part of the $5.4 billion allocated in the bill for wildfire mitigation and forest restoration, according to Alan Barton, director of NMFWRI.

Barton said SWERI is the result of congressional legislation passed in 2004 that charged the three institutes with promoting adaptive management practices.

Each institute engages in its own range of monitoring, restoration, and research projects, but Barton says the funding from Congress will enable the three institutes to work together more closely.

“There are five parts to the SWERI portion of the infrastructure act,” said Barton. “But the significant project in there is taking the New Mexico vegetation treatment database that was created and is managed by the Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute, and turning it into a national database.”

According to Katie Withnall, the geographic information systems (GIS) specialist at NMFWRI, the vegetation treatment database currently maps over 50,000 treatment projects across New Mexico and southern Colorado.

She said most treatments involve selective tree removal, but that the database is categorized by treatment types, which include physical, chemical, fire, and biological methods.

“Most of the treatments are for forest management for the prevention of catastrophic wildfire. A lot of that is thinning and prescribed fires,” said Withnall.

“We get data primarily from some of the bigger agencies—the Department of Agriculture and Department of Interior, the Forest Service, BLM, and New Mexico State Forestry, which is a big one that works on private land,” added Withnall. “We also get data from the tribes, Soil and Water Conservation Districts, some municipalities, and the State Land Office.”

Withnall said the database provides the information needed for fire modeling, which can help predict wildfire risk, and it helps land managers with cross-boundary planning.

“With a database like this, people can see what’s on the other side of the fence line when they’re planning their own treatments,” explained Withnall.

Barton said mapping treatments provides the infrastructure that facilitates the work on the ground. “Congress is committed to the database, and people in forestry see the value of this. It will be a really valuable tool once it’s up and running,” said Barton.

“The question we’re grappling with right now is, how do we take that map and turn it into a nationwide map. That was the charge that Congress gave us,” said Barton. “But not every state looks like New Mexico—some states have much more intensive forest management, and some states have very few forests, and little forest management.”

Barton said SWERI will receive the funding over five years.

He said creating a national vegetation treatment database and conducting research on treatment effectiveness—among other projects, will require SWERI to expand their staff, creating high quality jobs in New Mexico and the Southwest.

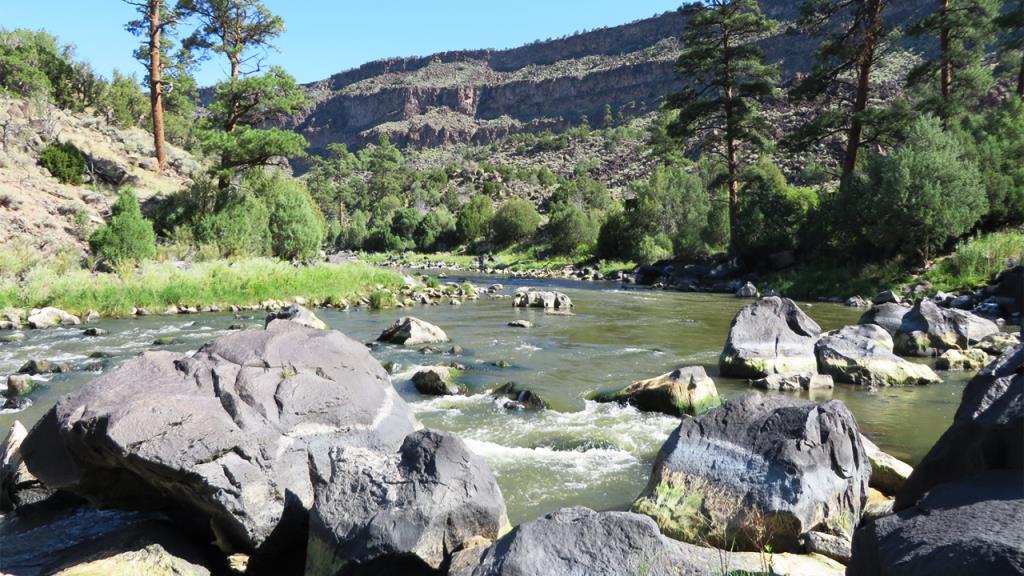

Photo of Guadalupe Mountains courtesy of New Mexico Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute.