This Feature Article for REVITALIZATION is by David Hill and Chris Clark.

We have an opportunity to create a Restoration Economy in Great Britain. We could deliver the UK Government’s ambitions for a 500,000-hectare (1,250,000-acre) Nature Recovery Network as enshrined in the 25-year Environment Plan within 5 or 6 years, with the added bonus of delivering economic benefits to a new set of skilled labour in the rural environment where job prospects are currently challenging.

Farmers would be paid well for the things we want. The misery of hard work for no liveable income would be a thing of the past and our biodiversity would be valued and restored to its former glory.

Upland farming in the UK will move to producing environmental benefits such as high landscape quality and biodiversity, using livestock as the tools.

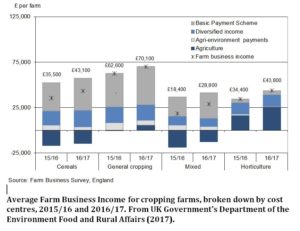

The economics of farming are in a parlous state. Defra’s own statistics from UK farms show that, across the average farm business, producing food loses money. Farm incomes are only just viable because of diversified revenue streams, agri-environment payments, the basic payment scheme (subsidy) and a spouses’ income.

When we leave, the EU subsidies will end albeit there will be some form of transition period. Many farmers in the UK will be unable to continue farming especially in places such as the uplands of Britain where they cannot move into other types of farming systems, being constrained by altitude, climate, a restricted growing season and poor nutrient conditions.

We already know that upland farmers are in trouble. Analysis of their individual farm accounts has shown that upland farmers believe increasing stock numbers enables them to generate more produce and therefore more profit.

However, the relationship between increased stock and increased profit is highly non-linear. Having to fight the harsh conditions of the upland environment by increasing feed, increasing fertiliser applications on grass and increasing veterinary and medical interventions, creates a disproportionate upward spiraling of costs and pushes margins further into the red.

Where upland farmers have been advised to cut their stock numbers rather than increase them (as might be a natural response in the face of falling margins) and in so doing dramatically cutting inputs, only then have margins moved into the black or at the very least mitigated losses. Where the focus is on chasing production rather than margin, any farm, irrespective of whether it is upland or lowland, is likely to suffer the same financial fate.

Farming will therefore have to change and that is a good thing. We will need much more sustainability in our farming practices using agroecological processes such as nutrient cycling, biological nitrogen fixation, allelopathy, natural predators, protecting and enriching soils and soil structure, mixed cropping and crop and grass rotations.

We will need a significant reduction in the use of inputs such as fertilisers and pesticides, less reliance on expensive human-driven machinery, and fewer people working in the fields. Upland livestock farming will need to change to use stock as the tools to create and manage environmental benefits.

This site has been restored from an overgrazed and devastated area of land set in an iconic landscape. ‘Devastation’ farming is a result of many years of poor practice in an effort to make a living from the land incentivized or kept going by EU subsidies.

Agricultural innovations will further change how we farm such as robotics, laser spraying, precision and minimized pesticide applications, minimum or zero tillage and laser drilling.

These innovations are highly likely to increase yields in the lowlands almost certainly using less land, thereby creating opportunities for restoring biodiversity, both within the farm (within fields or whole fields termed land sharing, the basis for sustainable intensification) or across catchments (farm-scale or land sparing).

But, without subsidies the economics of farm production are not likely to improve unless food prices increase significantly, which would be politically damaging even if sensible for farmers in every other respect.

In fact, they could get worse since the market advantage provided by EU membership will no longer exist. That is, unless we pay farmers to restore biodiversity as a public good that has public value. And the value of that to upland farmers in particular will become critical.

Upland farms are a special case since they can only grow livestock. But the uplands are also amongst the most biodiversity-rich areas of the UK, holding core concentrations of iconic species such as breeding Curlew, Redshank, Lapwing, Merlin, Ring Ouzel, Twite, Red and Black Grouse, as well as upland hay meadows, peatlands, blanket bog and upland heaths.

In addition, they provide a range of critical ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, holding water in the hills to reduce flooding down country, providing large parts of the UK with water and the means of reducing water discolouration. It is recognized that natural capital assets such as biodiversity and ecosystem services provided by the uplands should attract investment and what better way to do it than through environmental land management contracts with upland farmers.

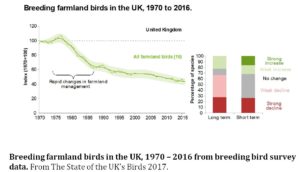

The UK is one of the most biodiversity-impoverished places on earth. That we have lost so much natural and semi-natural habitat and species abundance, especially over the past 60 years, is, from an ethical and moral viewpoint, nothing short of catastrophic. By land area agriculture has caused the greatest losses to biodiversity – 97% of meadows have been destroyed since the Second World War; since the early 1970’s Corn Buntings have declined by 87%, Skylarks by over 75%, Linnets by 76% and Turtle Doves by 95%.

The UK is one of the most biodiversity-impoverished places on earth. That we have lost so much natural and semi-natural habitat and species abundance, especially over the past 60 years, is, from an ethical and moral viewpoint, nothing short of catastrophic. By land area agriculture has caused the greatest losses to biodiversity – 97% of meadows have been destroyed since the Second World War; since the early 1970’s Corn Buntings have declined by 87%, Skylarks by over 75%, Linnets by 76% and Turtle Doves by 95%.

These birds are indicators of a lowland farming system operating in an utterly unsustainable manner in terms of the biodiversity asset. The graphic highlights the management practices that have driven these losses. Many lowland areas of the UK have effectively become ‘green concrete’ as far as biodiversity is concerned.

The UK has lost 97% of its traditional hay meadows since 1945 as a result of farming intensification. Relatively small scale restorations have been taking place for the past decade but now there is an opportunity to pay farmers to mainstream restoration at a greater scale, bringing back lost species and habitat. Ecotourism thrives in such areas and further boots the rural economy.

It is widely accepted that the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has been the main cause of this biodiversity loss through promoting the production of cheap food. Some £3.2bn of public subsidy has been spent annually to support a major loss-making industry that has significantly damaged our biodiversity and cultural heritage.

The losses are even greater when externalities are factored in as demonstrated by the Government’s Natural Capital Committee and the Sustainable Food Trust’s “The Hidden Cost of Food” report of 2017.

So, on the one hand farming cannot survive without payments from the taxpayer. On the other, the critical loss of biodiversity and the sterilisation of the countryside over the past 60 years, has been a price too high. We need to bring these two factuals together in a win-win opportunity, an opportunity provided by new rules and a new payment model that we can put in place after leaving the EU.

It is the Government’s intention that post-Brexit the old-CAP money will be paid out to farmers entirely for delivering environmental goods and services, for example by restoring biodiversity at scale. These funds, alongside others (such as from biodiversity offsetting and, potentially, corporate natural capital accounting) should be used to build a Restoration Economy, a move that would transform how the countryside looks.

The River Swale catchment is an iconic landscape and pert of the Yorkshire Dales National Park. Farming here is marginal at best and the historical overgrazing of the past provides lessons on how we should restore ecosystems in the future.

Reversing the devastating impacts of industrial farming by providing farmers with a proper income stream secured via locally relevant, 25-year contracts in accordance with a management plan for their farm, would stitch back the fabric of the British countryside and provide farmers with a good living.

Payments would be made on the basis of delivering results ie they would be outcome focused, unlike the current subsidy and agri-environment payments regime where the former are paid irrespective of environmental performance and the latter are paid on the basis of complex outputs which don’t make as significant a contribution to environmental gain as they should. There is a range of management interventions that could be paid for to rebuild biodiversity in the countryside.

The following positive management interventions could be paid for by conversion of subsidy money into environmental land management contracts:

- Unsprayed margins, conservation headlands, wildflower margins, beetle banks;

- Skylark and Lapwing plots;

- Pond and wetland creation;

- Pollinator strips, wild bird seed mixes;

- Water course buffer strips;

- Overwinter stubbles, reduced tillage;

- Wood meadows;

- New woodland;

- New and restored meadows;

- Water level management;

- Arable reversions eg to heathland;

- Managed ‘rewilding’;

- Scrub and grassland mosaics;

- High Nature Value farming (e.g. upland breeding wader habitat);

- Sustainable cropping systems; and

- Peatland restoration.

Where farmers increase their stock numbers in the belief of generating greater income, their farm businesses often crash into the red because of the non-linear extra costs of veterinary and medical interventions, increased fertilisers and increased feed as they try to fight against the vagaries of high altitude, a wet and cold climate, and poor soil nutrients.

Farmers will need effective long-term contracts commercially priced to offer core incentivisation to the land manager, simple administration, lack of complexity around compliance, and flexibility ie without rigid rules.

There needs to be a formal contracting environment where farmers are either targeted and contracted to deliver specific requirements (such as listed in Table 1) or the specifications are put out to tender (eg via reverse auction) again identifying exactly what the money is buying.

The independently established contractual model, we believe, offers the best opportunity of delivering what society requires from farmers in order to improve the environmental performance of farming. Farmers would bid to deliver either singly or, at catchment scale, by working in collaboration with each other.

Where farmers work together to provide greater scale biodiversity conservation, the areas of land over which biodiversity could be restored would be substantial.

Restoration over large tracts of land delivers more biodiversity than small fragments, so farmers should be encouraged to collaborate and work together to secure the funding and in so doing, to build resilience into their business models.

Restoration over large tracts of land delivers more biodiversity than small fragments, so farmers should be encouraged to collaborate and work together to secure the funding and in so doing, to build resilience into their business models.

Many farmers, especially in the uplands, are at financial breaking point. Increasing stocking densities only creates more financial burden. Leadership is required to turn the need and desire to restore the countryside and the biodiversity it should contain, into an investment opportunity using the money that is currently paid to subsidize unsustainable farming systems.

Innovation in lowland farming will further drive the opportunities for the restoration of biodiversity.

This paper is based in part on a report in the Institute of Economic Affairs (November, 2018) titled “The Effect of Innovation in Agriculture on the Environment“.

Featured photo of native red squirrel (whose populations are being restored) courtesy of ©Scotland: The Big Picture. All other photos courtesy of the authors.

About the Authors:

Professor David Hill CBE, DPhil(Oxon), CEnv, FCIEEM is Chairman of the Environment Bank Ltd. David has a strong professional and personal interest in biodiversity conservation, was a founding member of Natural England, the governments’ statutory advisers on the natural heritage, and its Deputy Chair from 2011 – 2016.

He is the Chairman of Plantlife and the Northern Upland Nature Partnership, a Board Trustee of the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation and a Commissioner with the RSA Food Farming and Countryside Commission. He founded The Environment Bank in 2009 (www.environmentbank.com) and has a farm in the Nidderdale AONB and meadows in Swaledale that comprise part of a Special Area of Conservation for their botanical importance.

Chris Clark, with his wife Fiona, owns and manages Nethergill Farm (www.nethergill.co.uk) . They are currently building an eco-hill farm business with a sustainable added-value meat activity, an educational and field study facility and eco-tourism holiday lets. He is a Partner in Nethergill Associates, a business management consultancy currently assisting with the conjecturing and management of future farming uncertainties in the Yorkshire Dales, Nidderdale, North York Moors, the Lake District and Surrey.

Chris Clark, with his wife Fiona, owns and manages Nethergill Farm (www.nethergill.co.uk) . They are currently building an eco-hill farm business with a sustainable added-value meat activity, an educational and field study facility and eco-tourism holiday lets. He is a Partner in Nethergill Associates, a business management consultancy currently assisting with the conjecturing and management of future farming uncertainties in the Yorkshire Dales, Nidderdale, North York Moors, the Lake District and Surrey.

A former farm tenant and farm manager, he now has thirty years of business management experience, many within the agriculture and allied food industry, of which over thirty years were managing his own businesses. Nethergill Associates has expertise in financial management, marketing and farm business planning. Chris is a Member of the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority.