Much has been said about the devastating social and economic impacts of America’s post-WWII love affair with the automobile. Short-sighted urban planners across the country subsequently did more physical damage to the nation’s cities in a few decades than all of America’s foreign military enemies had achieved in the history of the country.

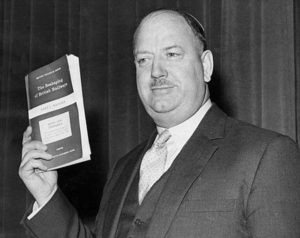

But the U.S. wasn’t alone in this car-crazed planning nightmare.Over half a century ago in Great Britain, the Beeching Report was published, spelling the end of hundreds of miles of British railway lines and stations.

Pretty much immediately, local campaigns sprang up to protest what became infamously known as the “Beeching Axe”. For instance, a museum in the center of Wisbech, a Georgian town of 30,000 souls in East Anglia, proudly displays the original manuscript of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. Those were days in which Wisbech prospered.

The frenzy of railway building in the 19th century gave the town three stations. Now it has none. The last passenger train left in 1968, five years after the report “The Reshaping of British Railways” by Dr. Richard Beeching, chairman of British Railways (BR), on the future of rail, which led to the closure of nearly a third of Britain’s 17,000 miles of track and a third of its 7,000 stations.

That clinical and ruthless assessment of what was required to put the railways back on stable footing won many admirers in the then-Conservative government.

They embraced Beeching’s proposals and were quick to implement his report’s recommendations. Few alternatives were offered. Wisbech has suffered economically, as did many others.

Progressive opponents at the time argued that Beeching had paid scant attention to the social importance of the railways. Many argued that the closure of many lines in rural Britain would isolate communities. They were right, maybe even more so than they realized. As a local Labour MP argued at the time, the railways were “a form of social service, which is as essential as the supply of electricity, gas, water and the National Health Service.”

British Railways, which from 1965 traded as British Rail, was the state-owned company that operated most of the rail transport in Great Britain between 1948 and 1997. It was formed from the nationalization of the “Big Four” British railway companies and lasted until the gradual privatization of British Rail, in stages between 1994 and 1997. In 1962, it was designated as the British Railways Board.

This period of nationalization saw sweeping changes in the national railway network. By 1968, steam locomotion had been entirely replaced by diesel-electric locomotives (except for one narrow-gauge tourist line). Passengers replaced freight as the main source of business. And, of course, there were the massive closures.

Now, Britain is joining dozens of other countries around the world in recognizing that a healthy, modern rail network is the backbone of a national economy, and that overly car-centric urban planning has been a monumental mistake. Over 50 lines have been reopened.

Ins some parts of the UK, many former lines were resurrected as part of the new “Heritage Rail” sector, while many successful community rail partnerships have also flourished. Elsewhere, disused lines have been repurposed as popular cycle and walking tracks.

UK transport secretary Chris Grayling has announced that more closed rail lines could be re-opened. This would reconnect many British towns and regions, most likely resulting in dramatic economic revitalization.

It is a remarkable new trend. After the war, many thought that roads would rule and rail would go the way of canals. When Milton Keynes—a new town that was the pride of the urban planning profession at the time—was built 55 miles north of London in the 1960s, it was deemed not to need a station. That costly mistake was finally rectified when one was finally opened in 1982.

In 2015 6.6 million rail journeys started or ended in Milton keynes. Traffic on other restored lines has boomed, too. The track that re-opened in 2015 from Edinburgh to the Borders expected 650,000 journeys in its first year. Half a million were made in the first five months.

The proposals, aimed to “reverse decades of decline” in the railways, have been praised as the “rebirth of the railways”. Yet huge investment is needed to truly revitalize the railways. Now, as in Beeching’s time, Britain’s railways are in need of updating. If Britain wants to see a rail system that is both economically viable and socially beneficial, there are some lessons to be learned from the wrongs of past policy.While there are many rail lines and stations up and down Britain that could bring great benefits if they were reopened. The Campaign for Better Transport has compiled a list of the 12 lines they believes have the strongest economic and social case for reopening:

- Ashington – Blyth – Newcastle: A victim of Beeching’s cuts, the line remained open to freight, meaning it would be relatively straightforward to reinstate passenger trains. Returning passenger services would significantly improve transport connections in a well-populated area in long-term economic decline. Northumberland County Council is supporting the scheme and reintroducing services will be one of the options in the new Northern Rail Franchise.

- Portishead – Bristol: Returning passenger services to the Portishead line would support this fast-growing part of Bristol’s commuter belt. The rail link would help tackle road congestion and reduce an hour long car trip during rush hour to around 17 minutes by train. A potential site for a new station at Portishead has been identified and the reopening has now got funding as part of a wider Bristol Metro network, with completion by 2019.

- The Worcester to Derby Main Line Railway between Stourbridge and Burton: Connecting Stourbridge, Walsall and Lichfield, reinstating this route would have both passenger and freight benefits. It would reduce road congestion and have the potential to make the controversial ‘Brownhills Eastern Bypass’ unnecessary, whilst allowing rail freight to bypass congested Birmingham and potentially remove heavy lorries off the roads.

- Leamside line: The 20 mile Leamside line in County Durham closed in 1991. The route has great potential for both freight and passenger services offering Durham’s 60,000 residents an alternative to the busy East Coast mainline and A1 motorway, and providing a freight link to the Nissan car plant in Sunderland. Reopening the line has been identified as a priority by both Durham County Council and the Freight on Rail campaign.

- Lewes – Uckfield: Reinstating this line would allow trains to run directly from west Kent and east Surrey to Brighton’s economic and social hub, significantly reducing pressure on the congested road network. It would also offer a diversionary route for the Brighton Main Line, an important strategic element the network currently lacks.

- Skipton – Colne: Restoring 11 miles of track would create an additional trans-Pennine rail route linking the West and East Coast Main Lines and connect the socially deprived and depressed areas of North-East Lancashire to the more prosperous West Yorkshire area.

- Leicester – Burton-on-Trent: Re-establishing passenger services on this 30 mile stretch of line, currently used for freight, would provide 100,000 people with access to the rail network and reduce pressure on local roads. The line would also provide a tourist route through the National Forest.

Fleetwood – Preston: Reopening the six mile line, closed to passenger services since 1970, along with two new stations would support economic regeneration in an area of 60,000 people and reduce pressure on local roads. - Wisbech – March: With around 30,000 people living in and around Wisbech, it is one of the larger settlements in the country not on the rail network and its isolated position has contributed to its economic decline. Reopening the seven miles of line between Wisbech and March would enable access to the regional centres of Peterborough and Cambridge and support regeneration initiatives.

- Totton – Hythe: Closed to passengers in 1966, the growth of many of the towns on this seven mile line, and the resultant pressure on the road network, has created a strong case for reopening. To maximise benefit to commuters a direct link with services to Southampton via Chandlers Ford would need to be established. Reopening costs are not thought to be prohibitive as the line has remained open for freight, serving the Fawley oil refinery.

- East-West Rail Link: This would re-establish the rail link between Cambridge and Oxford and improve rail services between East Anglia, Central and Southern England. The western section of the scheme from Oxford to Bedford was approved by the Government in November 2011, with completion expected in 2019.

- Bere Alston – Tavistock – Okehampton: This first stage of this line is already subject to a planning application and would link Tavistock with Plymouth and the national rail network, thereby enabling new housing while reducing traffic on the A386 and providing a tourist route to Cornwall and West Devon’s mining landscape. A second stage, reopening to Okehampton, would provide an inland alternative to the coastal route for trains to Cornwall.

“Filling in the missing links in our rail network offers the most cost effective way of alleviating congestion, reducing social isolation and improving economic prospects. Rail reopenings have huge local support, are good for business and can offer economically deprived areas a new lease of life. You only have to look at the number of passengers using the new stations and lines to see how viable and popular they are,” says Stephen Joseph of the Campaign for Better Transport.

Whether nationalized or in private hands, Britain’s railways are still in desperate need of investment, modernization and coordination. Finding the right process for renewal, such as this one, could mean economic rebirth for hundreds of British communities.

Featured photo (via Adobe Stock) is the train at the Giant’s Causeway and Bushmills Railway, Northern Ireland.

See Campaign for Better Transport website.

See December 7, 2017 article by Andrew Edwards in The Conversation.