Imagine if there were one simple action that city leaders could take to reduce obesity and depression, improve business productivity, restore urban beauty, boost educational outcomes, and reduce incidence of asthma and heart disease among their residents.

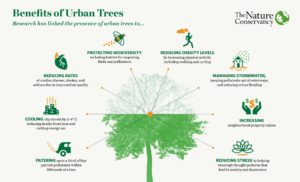

Urban trees offer all these benefits and more, such as enhanced economic growth: employers tend to locate in places with a good quality of life, which helps them recruit high-quality employees.

Yet American cities spend less than a third of a percent of municipal budgets on tree planting and maintenance, and as a result, U.S. cities are losing 4 million trees per year.

A new white paper, written by The Nature Conservancy with input from The Trust for Public Land and Analysis Group, identifies street trees as one of the most overlooked strategies for improving public health in our cities.

“For too long, we’ve seen trees and parks as luxury items, but bringing nature into our cities is a critical strategy for improving public health,” said Rob McDonald, lead scientist for global cities at The Nature Conservancy and first author of the white paper.

Every year, between 3 and 4 million people around the world die as a result of air pollution and its lifelong impacts on human health, from asthma to cardiac disease to strokes. Each summer, thousands of unnecessary deaths result from heat waves in urban areas. Studies have shown that trees are a cost-effective solution for both of these challenges.

Yet investment in planting new trees—or even caring for those that exist—is perpetually underfunded. Despite the overwhelming evidence cities are, on average, spending less on trees than in prior decades.

And too often, the presence or absence of urban nature—and its myriad benefits —is tied to a neighborhood’s income level, resulting in dramatic health inequities. In some American cities, life expectancies in different neighborhoods, located just a few miles apart, can differ by as much as a decade. Not all of this health disparity is connected to the tree cover, but researchers are increasingly finding that neighborhoods with fewer trees have worse health outcomes, so inequality in access to urban nature makes worse health inequities.

The white paper estimated that spending just $8 per person per year, on average, in an American city could meet the funding gap and stop the loss of urban trees and all their potential benefits.

The key, says McDonald, is to connect public health outcomes to urban trees. Communication and coordination between a city’s parks, forestry and public health departments is rare. Breaking down these silos can reveal new sources of funding for tree planting and maintenance.

The full paper offers several specific examples of innovative public-sector partnership and private sector investments that highlight the full societal value of urban trees. However, municipal leaders in communities of all sizes can begin to address significant health challenges by thinking creatively about the role of nature in cities and towns:

- Establish codes to set minimum open space or maximum building lot coverage ratios for new development.

- Implement policies to incentivize private tree planting.

- Break down municipal silos to facilitate various departments – such as public health and environmental agencies – to collaborate.

- Link funding for trees and parks to health goals and objectives.

- Invest time and effort in educating the public about the tangible public health benefits and economic impact of trees.

Featured photo via Adobe Stock.