Conservation projects around the world are helping to bring back endangered and extinct wildlife species. Not only is this important for the species themselves – preserving wildlife has positive impacts on human life, too.

Life on Earth is as much under threat from the loss of species and habitats as it is from climate change, says the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

When species and habitats shrink or disappear – the process known as biodiversity loss – it can threaten food supplies, jobs, economies and human health.

Climate change and its impacts, including warming temperatures, extreme weather and biodiversity loss, are accelerating this threat. Around one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, warns the United Nations.

To conserve nature and use its resources sustainably, “transformative changes” are needed across economic, social, political and technological areas, the UN says.

With this in mind, here are 8 species reintroduction success stories:

1. Cheetahs return to India

India’s native population of cheetahs was officially declared extinct in 1952. Now they’re coming back.

India’s native population of cheetahs was officially declared extinct in 1952. Now they’re coming back.

Namibia in south-west Africa has one of the world’s biggest cheetah populations, according to the BBC, and the country is sending eight of its wild cats to India to kickstart a five-year restoration program there.

The cheetahs will be based at Kuno-Palpur National Park in the state of Madhya Pradesh, which has the right climate and habitat for them.

India’s government said the return of the cheetah would have “important conservation ramifications” and help to stem biodiversity degradation and loss.

Some Indian conservationists remain skeptical of the idea, the BBC reports, saying that most of the country’s former cheetah habitats are shrinking because of pressure on land.

2. Wild bison return to the UK

In the United Kingdom, wild European bison have been released into a forest in Kent in south-east England to help manage the woodland.

Kent Wildlife Trust, which runs the project, says the natural behaviour of bison – like grazing, eating bark, felling trees and dust bathing – can restore the biodiversity of a landscape by helping other species to thrive.

It’s hoped the bison will help turn “a dense commercial pine forest into a vibrant natural woodland,” says The Guardian. They are the first wild bison in Britain for thousands of years.

3. Vultures are back in Europe

Vultures are “critical” maintainers of nature’s balance by rapidly cleaning up and recycling the bodies of dead animals.

But they have mostly disappeared from Europe over the past 200 years.

This was because of lack of food, habitat loss, persecution and poisoning, says Rewilding Europe, a Netherlands-based organization working to rewild landscapes across Europe.

Vulture populations are now slowly increasing, because of reintroduction programs and species protection, Rewilding Europe says.

Vulture populations are increasing in Bulgaria and Portugal and the bird is also being introduced into Croatia.

4. Missing lynx returns

The Eurasian Lynx – a type of wild cat – was considered extinct across almost all of Central Europe for 200 years, because of hunting and habitat loss, Rewilding Europe says.

The lynx has now been successfully reintroduced to Switzerland, Slovenia, Croatia, France, Italy, the Czech Republic, Germany and Austria.

This work has been going on since the 1970s, and there are now thought to be between 9,000 to 10,000 Eurasian lynx in Europe.

5. ‘Rat kangaroos’ return to Australia

In Australia, an endangered mammal called the brush-tailed bettong, or woylie, has been re-introduced after disappearing more than 100 years ago.

Also known as ‘rat kangaroos,’ bettongs are about the size of a rabbit and move around with a springy hop.

The animals used to be found in more than 60% of Australia, but were “almost wiped out when cats and foxes were introduced by Europeans,” according to New Scientist.

Twelve male and 28 female woylies have now been re-introduced to mainland South Australia.

The animals are important earth engineers. By dispersing seeds and nutrients while digging up tonnes of soil every year, they improve habitats for other species, New Scientist explains.

6. Ferrets breeding in the US

A type of weasel called the black-footed ferret was once considered the rarest mammal in the world, says the National Parks Conservation Association in the United States.

The ferret was officially recognized as threatened in 1967 and was nearly wiped out in some parts of the US by human extermination of prairie dogs, the ferret’s main source of food.

By 1987, only 18 black-footed ferrets were thought to be left in the world. These animals were put into a captive breeding programme and ferrets started to be re-introduced into US national parks in 1994 and 2007. About 1,000 black-footed ferrets now live in the wild.

7. Red kites return to the UK

Red kites, a large bird of prey, were driven to the brink of extinction in England by the end of the 19th century, as they were considered a threat to game birds and pets.

But the reintroduction of red kites to the UK has been “one of the greatest conservation success stories of the 20th century,” says the Chilterns Conservation Board.

Red kites started breeding in the Chilterns, one of 38 protected ‘areas of natural beauty’ in England and Wales in 1992, during a four-year reintroduction project.

There are now thought to be at least 1000 breeding pairs in the area.

Red kites have also returned to other parts of the UK in Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

8. China’s wild horses back from the brink

An endangered wild horse species called Przewalski’s horse is said to be the world’s only truly wild horse.

The horses were once found throughout Europe and Asia.

They can now only be found in reintroduction sites in Mongolia, China and Kazakhstan, according to the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute in the US.

In China, Przewalski’s horse became extinct because of “excessive poaching and environmental degradation,” says the Global Times.

China began reintroducing Przewalski’s horses from the UK, US and Germany in 1985, and has since bred more than 800 wild horses across six generations.

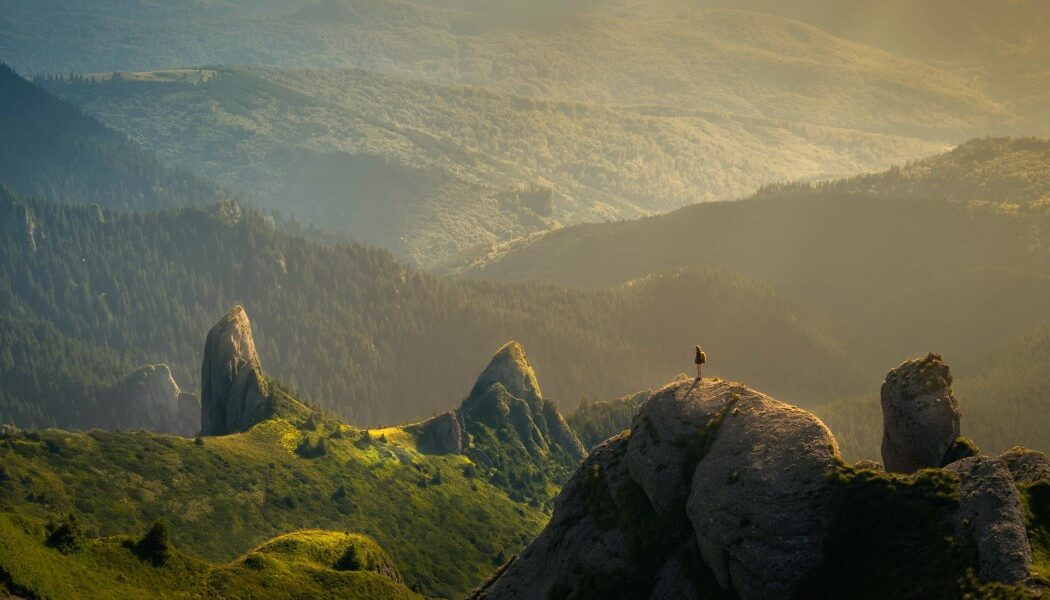

Featured photo is by David Marcu via Unsplash.

This article by Victoria Masterson originally appeared on the website of the World Economic Forum. Reprinted here (with minor edits) by permission.