This issue’s Sneak Peek feature—which excerpts my upcoming third book, RECONOMICS (coming January 2020)—deals with the role of government in creating or sustaining resilient prosperity and restoring our global climate. The excerpt appearing in the next issue will deal with the role of colleges and universities.

The Role of Higher Education in Advancing Resilient Prosperity and Climate Restoration

When did you last meet someone with a Ph.D. or a Master’s in revitalization? Despite trillions of dollars spent annually worldwide on bringing places back to life—and despite the high rate of failure of such expenditures—academia turns a blind eye to revitalization. A shift towards a more rigorous process could start in your community…if the appropriate university is based in your region.

They don’t mind teaching and researching the technical disciplines that renew specific assets: there are many courses in historic preservation, brownfields remediation, infrastructure renewal, and the like. But when it comes to the actual goal of reversing the stagnation or decline of a place, our institutions of higher learning seem content to allow their students to remain in a state of ignorance.

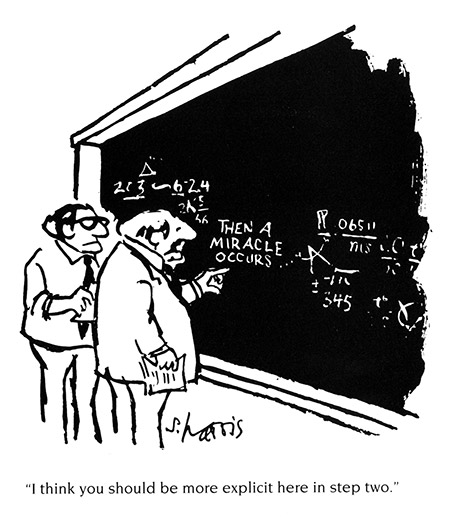

by Sidney Harris. [©Copyright 2003, The New Yorker.]

I’ve long used the preceding cartoon in my talks and leadership workshops. It’s a perfect depiction of the current “practice” of revitalizing places. If places want revitalization, why don’t they allocate money directly to achieve that goal? Why don’t we manage it professionally? Why don’t we even know what it is? Why is the prevalent paradigm “do a bunch of good stuff and hope a miracle occurs”?

If communities really want revitalization or Resilient Prosperity, why is no one in charge of it? Have you ever seen a significant local, state, or federal government agency with “revitalization” in its name? Or seen “revitalization” in the name of a significant ongoing public budget line item, or in the title of an influential public leader? But even if you were to appoint someone locally to head-up their revitalization and/or Resilient Prosperity efforts (Tactic #2), wouldn’t it be better to hire a person with relevant training, certification, or degree?

The closest title I’ve encountered is “Community Development Director”. Some folks with that title are effectively Revitalization or Resilience Directors, but most interpret their role far more narrowly. “Community development” is a catch-all phrase, not a discipline. There are also “Community Economic Developers”, but that only narrows the scope of action still further.

Some practitioners rightly differentiate between business development and the more comprehensive concept of public economic development. But the “economic development” tends to focus on serving the economy in the short term (such as via sprawl), rather than on infill, neighborhood revitalization, and cultural or environmental factors that might be of more long-term economic value.

Those involved in revitalizing places generally operate in silos. They’re like heart surgeons who can fix valves, but are stymied if asked to define—much less restore—health. Some silos are defined by asset type or by profession, such as infrastructure or planning. Others by geography or jurisdiction: city, county, region, downtown, neighborhood, etc. But when everyone is in charge, no one is in charge.

Now, if a place is happy just doing renewal projects on an ad hoc basis to address immediate needs, a more-disciplined approach isn’t needed. But if they wish to ensure that their efforts actually fix the present (tactical renewal) and the future (strategic renewal), ad hoc won’t cut it.

Universities must take seriously this challenge of creating professionals who revitalize our increasingly urbanized world. They must realize that urban planning degrees don’t address revitalization (nor are most planners in a position to manage it, even if they understood it). Nor do degrees in public policy, public administration, public works, architecture, landscape architecture, civil engineering, and so on.

While pure research is essential, we must prevent revitalization research and curricula from becoming like economics. Most economists have only two career choices: 1) teaching economics, and 2) helping governments or corporations justify decisions they’ve already made, or actions they’ve already taken. Preventing such a dismal fate for students of Resilient Prosperity or revitalization would require a solid basis in reality. This could start with a partnership between a university and the city that house it:

- The school would get access to local data, lessons learned, and government internships.

- Local officials could do classroom lectures, while getting access to new research and curricula.

How could a discipline and profession focused on revitalization and/or Resilient Prosperity come about? There are three standard routes:

- Academic: This would require a benefactor to endow a chair to fund and advance research, curriculum development, and degrees;

- Governmental: A national agency (such as HUD or EPA in the U.S.) might perceive the need for such a discipline at the local, state, and national levels, and provide funding to schools or organizations to create the appropriate research, curricula, and certifications;

- Private: A professional association could be formed for this purpose. Its members would come from the myriad fragmented current disciplines that address revitalization. This could be a new organization, or a new focus of an existing organization.

A revitalization professional would help ensure that each project increases community vitality, and would help it stay focused on the long-term. Just as publicly-traded corporations tend to focus on quarterly results to please Wall Street, so too do elected leaders tend to focus on expenditures and budget cuts that will produce results within their term of office. The result is usually underfunding what’s lasting, important, and intelligent, and over-funding what’s quick, superficial, and emotional.

In his Harvard Business Review article “The Execution Trap”, Roger Martin, former dean of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, says separation of strategy and execution is a major flaw in executive thinking. We are all arguing the relative importance of good strategy versus good execution as if they were unrelated, so thinkers and doers work in dysfunctional isolation from each other.

Communities suffer a worse problem. Not only do they separate implementation from strategy, but what they refer to as “strategy” is often just hope. Dean Martin (no, not that one) recommends that we abandon the old model of brilliant thinkers on top and choiceless doers on the bottom. He recommends a feedback model allowing those on top to dictate broad guidance, and allowing implementers to provide feedback on how well those rules work in reality.

So too should those in charge of revitalization work from a clear vision of their desired future, against which they would compare each new project. That vision would yield a few simple rules: broad decision guidelines that allow innovation at the local level (such as secure, inclusive, and green). A good system allows innovations to flow back to the top, so each place can discover what works locally. This frees leaders to abandon false assumptions about what should work (usually based on mimicking others).

Martin says separation of strategy and execution is promulgated by management consulting firms. Why? Because it allows them to blame failures on clients’ flawed implementation of their genius strategy. Urban planning firms also tend to avoid implementation. When a plan fails, they blame the mayor, the city council, unruly developers, or the citizens (NIMBYism, etc.) for screwing up their perfect strategy. Delivering a plan is a guaranteed “success” for client and vendor alike. Implementing it? Very risky.

The psychological and health benefits of living in a revitalizing place are legion. Some are surprising. Did you know it cuts your electricity bill? Research led by Ping Dong of the University of Toronto found that people who feel more hopeless about their economy and employment opportunities prefer brighter lighting. 20.6% more power is used per 1 point less hopeful (9-point scale) folks feel about the future.

Another insight into the revitalization dynamic that we wouldn’t know without academic research is why post-disaster cities are often more-resilient cities. In 2012, Eiji Yamamura of Japan’s Seinan Gakuin University published a paper called “Atomic bombs and the long-run effect on trust: Experiences in Hiroshima and Nagasaki”, based on researching survivors of those 1945 atomic bombings. He found they were 16%-17% more likely than normal to trust other people. Trust is a crucial element of revitalization. It’s the transactional lubricant of all economies: the more there is, the more efficiently they operate. Those leading post-disaster rebuilding projects should tap this silver lining.

Council reviewed proposals to revitalize the borough’s major thoroughfares Tuesday, along with a code enforcement ticketing program intended to help clean up eyesores. Revitalization proposals include a slogan contest, hanging banners and planters, brochures and street landscaping. Borough Manager Don Curley requested … $1,000 for brochures and up to $6,000 for banners and planters.

– From July 21, 2015 article in The Times Herald, titled “Bridgeport (CT) council reviews revitalization proposals”

Due to the lack of academic and practitioner rigor, a large “superficial revitalization” industry has emerged. Mayors desiring the appearance of action often commission comprehensive plans from private planning firms, with no intention of implementing them. They can also buy “instant revitalization” in the form of street banners that provide an illusion of rebirth.

Note: The above criticism is only directed at places that confuse such purchases with actual revitalization. Banners are useful in providing visual cues to behind-the-scenes revitalization activities. They can also provide visual cohesiveness for revitalized urban districts, especially those that reuse existing buildings. For instance, Ryerson University in Toronto made brilliant use of abandoned buildings to expand its downtown campus, which helped revitalize that area. But since the buildings weren’t originally designed as part of the campus, there’s little shared architectural vernacular for the Ryerson identity. The school inexpensively solved the problem via banners that let people know when they are on the campus.

The social impacts of revitalizing a place are probably far deeper and broader than we know. I’d love to see graduate students comparing the health and psychological factors in revitalizing versus devitalizing places. Even better: randomized controlled trials for various revitalization tools and factors. A great step towards this hard-data direction is the new ISO 37120 standard, comprising indicators for city services and quality of life. This combines government-collected “Big Data” with citizen-acquired data. As wearable technology takes off, these quality of life indicators will come closer to real-time.

Most cities are being hit with rapid population growth at the same time they’re experiencing rapid aging, deterioration, and design obsolescence of their infrastructure. Most young people want to leave the world a better place, but few universities teach restoration or revitalization. Seems like a mismatch. Why isn’t community revitalization currently taught in universities? Money and (again) fear.

Money because most universities only have one mode for entering a new realm of research and curriculum development: If someone walks through the door with a big check and asks them to focus on a subject, they will endow a research chair and create coursework. Otherwise, forget it. Academic institutions (with very few exceptions) have almost no internal capacity for institutional innovation.

Fear because revitalization is emergent and seems magical…non-intellectual. Why do all medical schools teach brain structure and function, but few teach consciousness? Fear of ridicule. Consciousness (like revitalization) is an emergent phenomenon, reeking of mysticism. Appearances are everything in today’s image-conscious, corporate sponsor-driven world of academic research. The best place to develop a revitalization discipline might be at one of the 40+ universities that already study and teach complexity science. They are already comfortable with the concept of emergence.

Many are happy to work on a piece of the urban, rural, or environmental revitalization puzzle. But we shy away from responsibility for the whole. If a place revitalizes, we share the glory. If it doesn’t, it’s not our fault: we did our part. Fear of failure is also why we can’t earn a degree in revitalization: academics perceive its complexity and worry that it’s not understandable. So why risk studying or teaching it?

“I don’t have any faith at all,” said Jimmy Allen, 66, a former gang member who now works with neighborhood youth. He says many of the people involved with the Promise Zone don’t come from or represent the community. “I think the companies will do well. I think the universities will do well, (and) some of the organizations that do their reports. But the neighborhood is going to still be stagnant.” He wants to see funding go to grass-roots community groups “so we can make sure our children and our residents and our businesses come up.”

– “A promise yet to be delivered in West Philadelphia” by Kate Kilpatrick, Al Jazeera America, Jan. 21, 2015

Places are like people: About 1% are born into great wealth, and thrive no matter how poorly they perform. But for most places and people, life comprises a pattern of initial growth, followed by alternating devitalization and revitalization.

The causes, frequency, and amplitude of these economic, social, and ecological tides vary from one place to another. But the underlying dynamics are universal, and deserve to be studied…especially if we wish to create Resilient Prosperity in an era of constant crisis and unprecedented uncertainty. Schools can help reduce our vulnerabilities in these broken times.

About the Author

Storm Cunningham is the publisher of REVITALIZATION.

Since 2002, he has been a full-time revitalization process planner for organizations, communities, and regions. He is also a professional speaker and workshop leader on community revitalization, economic resilience, and natural resource restoration. His clients include national and local governments, universities, and non-profits in over a dozen countries.

He lives in Arlington, Virginia, and is the author of two highly-acclaimed books:

The Restoration Economy (Berrett-Koehler, 2002), and Rewealth (McGraw-Hill Professional, 2008).

See http://RestorationEconomy.com and http://Rewealth.com for more information about these books.

See http://StormCunningham.com for more on his work.

Storm can be reached at 1-202-684-6815, or at storm@revitalization.org