This issue’s Sneak Peek feature—which excerpts my upcoming third book, RECONOMICS (coming January 2020)—explores with the role of foundations, especially community foundations, in creating resilient community prosperity and global climate restoration.

The Role of Foundations in Advancing Resilient Prosperity

In his 2014 book, “Rebalancing Society: Radical Renewal Beyond Left, Right, & Center” Henry Mintzberg says that healthy societies are built on three balanced pillars: 1) respected governments; 2) responsible enterprises; and 3) robust voluntary associations (nonprofits, NGOs, foundations, etc.).

When local, state, and federal funding for community improvement decreases to a crisis point, foundations often step in. There are three kinds of foundations. Private foundations get their funding from an individual, a family, or a company. The best-known are those set up by the industrialists of the 19th and early 20th centuries: Rockefeller Foundation, Ford Foundation, Carnegie Foundation, and so on.

Private foundations created by commercial banks often focus on community revitalization. This benefits the community and the bank, since revitalization increases both the value of real estate and the success of businesses. This reduces mortgage and business loan defaults. The Bank of America Charitable Foundation was created in 1958. It’s mission statement says “the Foundation funds (local) institutions to help enrich the community and advance overall community revitalization.” A more-recent such creation is the TD Charitable Foundation, created in 2002 by Canada’s TD Bank. Their stated mission includes “community revitalization and the preservation and development of affordable housing”.

There are two kinds of public foundations: grant-making charities (often fighting diseases or social problems on a national or global basis), and community foundations. What they have in common is funding derived from diverse sources; individuals, corporations, public agencies, and other foundations.

An example of a grant-making charitable group is the Foundation for Rural and Regional Renewal (Australia), which has a “Repair-Restore-Renew” disaster recovery program. Community foundations (often referred to as “place-based foundations”) are also grant-making public charities, but they differ in that their focus is defined by geography, rather than issue.

This section will focus primarily on the revitalizing roles of private foundations. We’ll return to community foundations in the “Tactic #6” section, since they are especially well-positioned to lead communities into the next generation of effective, efficient, and equitable Adaptive Renewal systems.

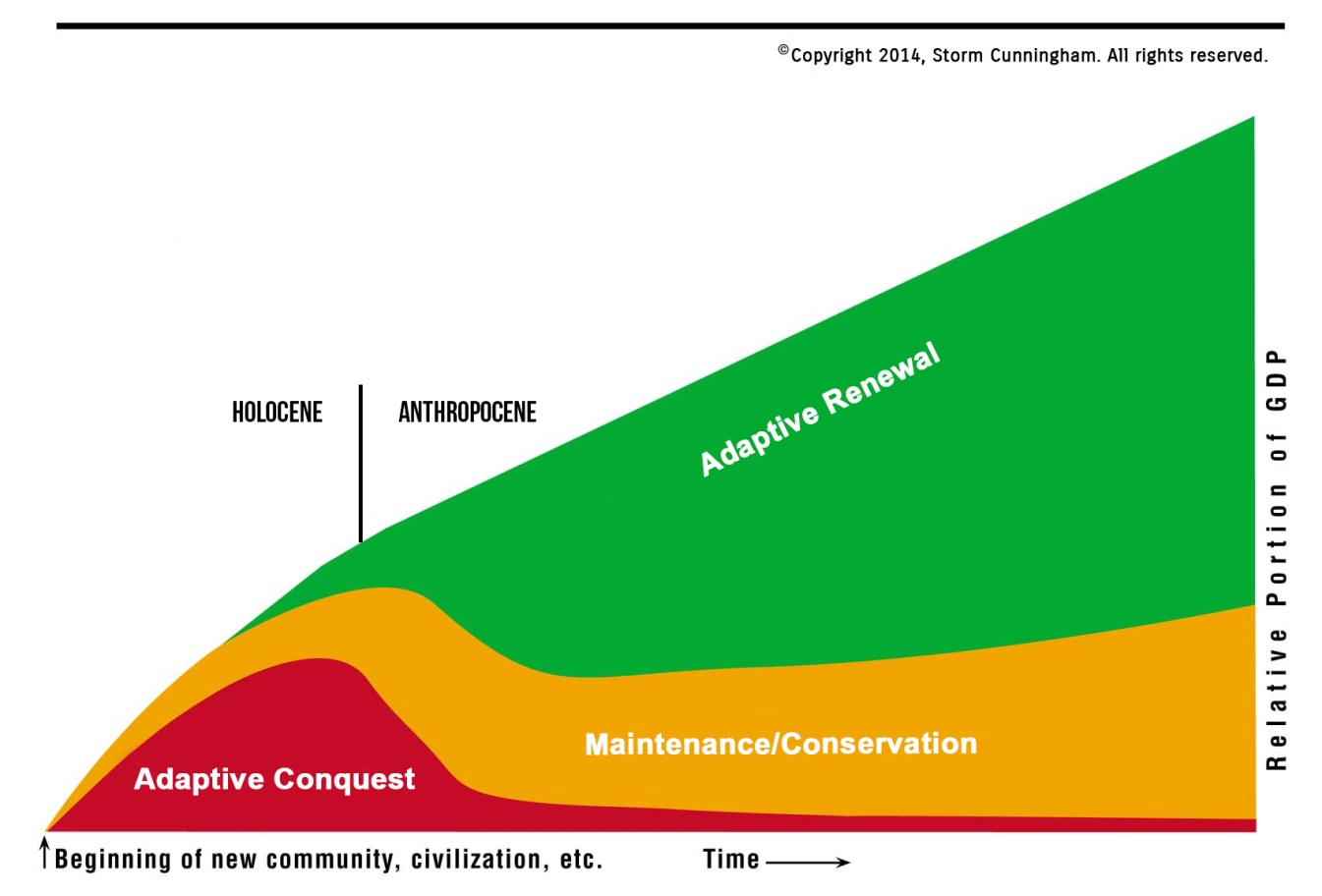

For the past two or three decades, most philanthropy related to helping communities and the natural environment has been focused on “greening” or “sustainability” efforts. This is all well and good, but let’s face it: it’s a bit late. Sustainable development is what we SHOULD have been doing for the past two centuries, but didn’t. The world is now so damaged and depleted that only restorative development can give us a healthier, wealthier, more beautiful future, especially in the face of rising populations.

In many cases, restorative philanthropy is hidden behind the labels of “sustainability” or “resilience”. Both are noble goals and necessary dialogs, but we can’t point to projects and say with confidence that they are sustainable or resilient. For how long? 10 years? 10,000 years? With what population? 7 billion? 70 billion? The best we can say is that they are less unsustainable, or more resilient.

Restorative development, on the other hand, is eminently measurable, truly sustainable, and resilient. We can measure how many more fish are in a restored river after a dam removal. We can measure how much less contamination is in a remediated industrial site. We can measure how much more a historic building is worth after renovation and reuse. Many aspects of revitalization are also measureable.

Reducing new damage and new waste is vital, of course. But it’s too late to rely on that: we need to undo existing damage and clean up existing waste. Anyone who’s satisfied with sustaining the world as it is just isn’t paying attention. Their heart’s in the right place, but who wants to sustain this mess? We need to revitalize the communities we’ve already created, and replenish the natural resources we’ve damaged and depleted. That’s regeneration, also called restorative development.

Now, restorative philanthropy is taking hold, joining the government and business spending that has long-dominated revitalization efforts. Philanthropic organizations increasingly realize that revitalizing communities and restoring natural resources is by far the most effective use of their precious funds.

The trend can only grow, since recycling and retrofitting our cities—plus repairing our natural resources—is the ONLY sure way to increase health and wealth in our broken world. Today, it’s hard to find a major private foundation that isn’t focusing on renewing the natural, built, and/or socioeconomic environments to some degree. A few quick examples:

- The New York Restoration Project is developing a shareable model for community revitalization with $250,000 from the Knight Foundation;

- The C.S. Mott Foundation funds the Flint Area Economic Revitalization for that stricken city;

- The Kellogg Foundation has given $2.4 million to LINC Community Revitalization Inc. in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and is supporting many revitalization efforts in Detroit;

- The distressed Anacostia area of Washington, DC wants to repurpose an ugly abandoned river bridge as a public park. The 11th Bridge Park combines four powerful revitalizing elements: connectivity, water, greenspace, and pedestrianism. Early backers: Educational Foundation of America, Horning Family Fund, Prince Charitable Trusts, and Fetzer Memorial Trust.

Winning design for 11th St. Bridge Park by OMA + OLIN (©Copyright 2014, OLIN)

While generally a negative, socially-destabilizing force, today’s wealth concentration trend has one positive effect: a growth in philanthropic funding. Zachary Mider, in the May 12-18, 2014 Bloomberg Businessweek, says “Over the past few decades, the rise in fortunes of the country’s richest people has created a golden age of philanthropy, comparable to the one that spawned the Carnegie and Rockefeller foundations a century ago. …Because Congress offers tax deductions for philanthropy, this growing breed of donor is deciding the fate of billions of dollars that would otherwise flow to the government.”

In the U.S. in 2013, university business schools received 67 single-donor gifts of over $1 million, the most ever in a single year. A 2014 study from the Boston College Center on Wealth and Philanthropy projects that a record $27 trillion is expected to be donated by Americans to charities between 2007 and 2061.

The wealth-concentration trend is now converging with the restorative development trend, also known as the Restoration Economy. The convergence has produced a powerful new trend: restorative philanthropy, which promises far greater, more-widely-felt impacts than most current forms of giving.

“Brain scans reveal that the mere thought of helping others by

planning to make a donation makes people happier.”

– from “Philanthropy has more intrinsic benefits than you think“, by Bruce DeBoskey, Denver Post, May 11, 2014

It’s not just “rising money meets rising need”: there’s a supreme level of satisfaction that comes with bringing dead or dying places back to life. This is driving the shift from “merely” reducing new damage (green/sustainable)—which is essential—to repairing existing damage (restorative).

Restorative philanthropy is now regenerating, renovating, renewing, remediating, replenishing and revitalizing more of our world with each passing year. Add to this grant-making the rapid growth of restorative impact investments—often by the same philanthropic entities—and the numbers start to get serious.

Some private foundations—such as the Walton Family Foundation, Orton Family Foundation, and Kresge Foundation—have practiced restorative philanthropy for decades, often focused on the U.S. “Rust Belt”. The Surdna Foundation is unique in that they focus on both community revitalization and nature restoration. This strategy makes them a leader in the fast-growing global restoration economy.

The best way to describe how private foundations can put a distressed city on the path to rapid, resilient renewal is via a dramatic success story. This following story is excerpted and updated from a case study in my 2008 book, Rewealth (from McGraw-Hill Professional).

In 1969, Walter Cronkite announced on national TV that Chattanooga, Tennessee had been labeled “the dirtiest city in America” by the U.S. government. Air pollution was sometimes so bad that people had to drive with their headlights on in the middle of the day. Motivating by a potent combination of humiliation and regulation, the city spent the next decade remedying the situation.

Chattanooga eventually won the EPA’s first Clean Air Award, but it’s what the city did after they cleaned their air that earned them global renown. By the early 80’s—despite their cleaner air—they were still losing 5000 manufacturing jobs annually. Crime was high, racial problems were rife, and the city was divided.

In 1986, Chattanooga began a revitalization process that took it from basket case to revitalization “poster child”. Two private foundations—both built on the fortunes of independent Coca-Cola bottlers—were directly responsible: The Lyndhurst Foundation and the Benwood Foundation. Their funding kicked off two years of public engagement and visioning, via the non-profit Chattanooga Venture. Virtually every good thing that has happened to the city in the past 30 years has its roots—directly or indirectly—in Chattanooga Venture’s network of “fixers”, and in their revitalization process.

The Lyndhurst Foundation, led by Jack Murrah (now retired), provided catalytic funding for virtually every major initiative that ignited Chattanooga’s rebirth. The Benwood Foundation provided follow-on support for most of these renewal initiatives, with a heavier focus on arts and culture. Chattanooga Venture created stakeholder cohesion.

Venture’s mission was to engage the public in the creation of a shared vision of the community’s future. That vision integrated the renewal of their natural, built, and socioeconomic assets with their dreams. It provided a home for that vision, and the resulting continuity allowed renewal momentum to build. Besides visioning, Chattanooga Venture provided learning: lectures by revitalization leaders from other cities, and field trips for local leaders to revitalized cities.

Crucially, Chattanooga Venture also provided a forum for effective, transparent public-private partnering, using a simple-but-effective process. They created a task force whenever new challenges and/or opportunities were identified. They chose people for these task forces—each possessing unique resources of potential value to the solution—who were in a position to be part of a partnership.

Chattanooga’s best-known feature, the Tennessee Aquarium, was added to their revitalized waterfront in 1992. The 21st Century Waterfront initiative was created when Bob Corker (now U.S. Senator) became mayor in 2001. It expanded and renovated the aquarium, Discovery Museum, and Hunter Museum of American Art, and created pathways from the Hunter to the waterfront. By 2005, when the 21st Century Waterfront plan was finished, the Tennessee Riverwalk had been expanded to 11 miles of trail down to the Chickamauga Dam, and over 1100 trees had been planted on this old industrial land.

Every $1 of public money invested in recreational space and art tends to attract about $13 of private investment. Chattanooga spent $9 million remediating the waterfront site of an old enameling plant. Via ecological restoration, they created the 22-acre Renaissance Park. Developers have now surrounded the park with $110 million worth of condos, stores, restaurants and a LEED-certified shopping center.

In 2011, Volkswagen opened the world’s only LEED Platinum-certified auto manufacturing plant on what was previously a highly-contaminated waterfront brownfield. The 1400-acre parcel was once an ammunition plant, manufacturing up to 30,000,000 pounds of TNT per month for World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

The transformation is dramatic: the new plant has 33,000 solar panels generating 9.5 million watts. VW went beyond green, to regenerative: they restored two creeks on the property to enhance habitat for native species, providing a wildlife corridor around the plant.

How did Chattanooga clinch this $1 billion, 3200-employee prize, over the dozens of cities vying for it? They offered $577 million of incentives to VW, but other cities made similar offers. The clincher: VW wanted the waterfront trail extended to their site, so employees could enjoy walking to the downtown. Quality of life and connectivity were thus the differentiators. As this is being written, VW has announced a $900 million expansion of the Chattanooga plant.

People move for reasons besides employment.

Pittsburgh’s net gain may point more to quality-of-life advantages than economic opportunity because the city’s job growth has not been that much better than the state’s….

– Kurt Rankin, economist at PNC Financial Services Group

Mayors and public leaders from around the globe make pilgrimages to witness the “miraculous” rebirth of Chattanooga. All of this came about because a private foundation funded the creation of what became a very effective Adaptive Renewal system (described in more detail in the “Tactic #4” section).

Maybe the ideal would be to have private foundations fund community foundations for this purpose. Someone must take the lead in advancing the practice of revitalizing places. Will it be government? Will it be universities? Will it be foundations? Will it be all, working independently, or all, working together?

The increase in climate change-related disasters is shifting our focus from sustainability to resilience, and to climate restoration, not just climate change mitigation (carbon-negative, not just low-carbon or carbon-neutral). There’s much overlap in their definitions, but sustainability efforts tend to focus more on preventing systems from being undermined by flaws in their basic design. Resilience efforts tend to focus on preventing systems from being undermined by external forces. The shift to resilience is a healthy one, since it gets closer to the heart of the issue: the regenerative capacity of places. The Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities Program (mentioned in the “Resilience” section) is the prime example.

In Jane Jacob’s 1984 book, Cities and the Wealth of Nations, she advocated for both ongoing efforts and for adaptive management: “In its very nature, successful economic development has to be open-ended rather than goal-oriented, and has to make itself up expediently and empirically as it goes along.”

Chattanooga’s waterfront aquarium. Photo credit: Storm Cunningham

About the Author

Storm Cunningham is the publisher of REVITALIZATION.

Since 2002, he has been a full-time revitalization process planner for organizations, communities, and regions. He is also a professional speaker and workshop leader on community revitalization, economic resilience, and natural resource restoration. His clients include national and local governments, universities, and non-profits in over a dozen countries.

He lives in Arlington, Virginia, and is the author of two highly-acclaimed books:

The Restoration Economy (Berrett-Koehler, 2002), and Rewealth (McGraw-Hill Professional, 2008).

See http://RestorationEconomy.com and http://Rewealth.com for more information about these books.

See http://StormCunningham.com for more on his work.

Storm can be reached at 1-202-684-6815, or at storm@revitalization.org