This Feature Article for REVITALIZATION is written by Steve Zwick, Managing Editor of Ecosystem Marketplace, where it originally appeared.

Freshman Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and veteran Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass) lit up the internet with their proposal for a “Green New Deal,” which does what U.S. negotiators refused to do at recent climate talks in Katowice, Poland: It recognizes scientific consensus on the need to reduce emissions and increase carbon sinks, and it sets ambitions based on it.

The proposal aims to slow climate change in part by “removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and reducing pollution by restoring natural ecosystems through proven low-tech solutions that increase soil carbon storage, such as land preservation and afforestation,” but also by working “collaboratively with farmers and ranchers in the United States to remove pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector … by investing in sustainable farming and land use practices that increase soil health.”

The proposal aims to slow climate change in part by “removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and reducing pollution by restoring natural ecosystems through proven low-tech solutions that increase soil carbon storage, such as land preservation and afforestation,” but also by working “collaboratively with farmers and ranchers in the United States to remove pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector … by investing in sustainable farming and land use practices that increase soil health.”

These are exactly the kinds of natural climate solutions that can deliver more than one-third of the mitigation needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s 2-degree target, but which get just 3 percent of dedicated climate finance.

Naturally, critics on the right have gone apoplectic, claiming that the proposals will slash fossil-fuel profits, killing jobs in the process. Those gripes, however, miss some basic economic realities, beginning with the fact that that profits aren’t jobs. In fact, they’re often the opposite: companies save money by cutting jobs.

Now, cutting jobs sometimes can benefit the economy if those jobs aren’t adding value, but the jobs that the New Green Deal generates do add value by paying farmers to plant trees and use winter cover crops that improve soil fertility and provide raw materials for biofuels. They also pay ecosystem entrepreneurs to restore rivers, and to turn soggy, unproductive land into wetlands that filter water, purify air and slow climate change — jobs that exist because companies that damage our environment have a responsibility to make us whole.

“Companies that don’t pay are guilty of theft,” says University of Chicago Professor Steve Cicala. “If someone has a better way of describing [the act of] taking something from someone without their consent and without compensating them, I’d be happy to use that term.”

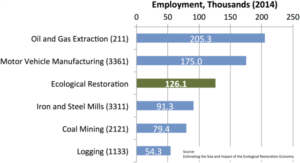

This isn’t pie-in-the sky. Those jobs are already part of a $25 billion restoration economy that directly employs 126,000 people and supports 95,000 other jobs, mostly in small businesses — according to a 2015 survey that environmental economist Todd BenDor conducted through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This isn’t pie-in-the sky. Those jobs are already part of a $25 billion restoration economy that directly employs 126,000 people and supports 95,000 other jobs, mostly in small businesses — according to a 2015 survey that environmental economist Todd BenDor conducted through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

That’s more jobs than logging, coal mining and iron and steel, as you can see on the chart to the left.

The restoration economy is already providing jobs for loggers across Oregon, and even some coal miners in Virginia, but it could disappear if the GOP environmental rollback continues. Here are 11 things you need to know to understand it.

1. It’s not solar and wind

The restoration economy is not to be confused with the renewable energy boom (PDF) that employs 374,000 people in solar parks and 101,738 on wind farms. Like those, however, the restoration economy is part of a burgeoning “green economy” that’s transforming forests, farms and fields around the world.

2. It’s government-driven

State and federal governments helped the wind and solar sectors get off the ground, but both sectors are humming along on their own because they provide a cost-effective way to produce electricity, which everyone needs.

The demand for restoration, however, isn’t as automatic as the demand for electricity is, because most companies and even some landowners won’t clean up their messes without an incentive to do so.

Economists call these messes “externalities” because they dump an internal responsibility on the external world, and governments are created in part to deal with them — mostly through “command-and-control” regulation, but also through systems that let polluters either fix their messes or create something as good or better than what they destroy.

Under the Endangered Species Act, for example, a local government that wants to build a road through sensitive habitat can petition the Fish and Wildlife Service for permission to do so. If permission is granted, it still has to make good by restoring degraded habitat in the same region.

3. It’s often market-based

Pioneered in the 1960s, environmental markets offer flexibility in meeting commitments. That local government mentioned above, for example, can either restore the land itself, or it can turn to a “conservation bank.”

These are usually created by green entrepreneurs who identify marginal land and restore it to a stable state that performs ecosystem services such as flood control or water purification. They make money by selling credits to entities — personal, public or private — that need to offset their environmental impacts on species, wetlands or streams.

At least $2.8 billion per year flows through ecosystem markets in the United States, according to Ecosystem Marketplace research.

4. Infrastructure also drives restoration

The federal government — especially the military — holds itself to high environmental standards, as do many states. Government activities alone support thousands of restoration jobs.

Government agencies are big buyers of credits, often to offset damage caused by infrastructure projects, but the link between infrastructure and restoration goes even deeper than that. In Philadelphia, for example, restoration workers are using water fees to restore degraded forests and fields as part of a plan to better manage storm runoff.

In California, meadows and streams that control floods are legally treated as green infrastructure, to be funded from that pot of money. “Green infrastructure,” it turns out, is prettier than concrete and lasts longer to boot.

Trump wants to “expedite” infrastructure rollouts, and he can do so without weakening environmental provisions by removing unnecessary delays in the permitting process (see point 11, below).

5. Markets can reduce regulations

Nature is complex, and rigid regulations often fail to address that complexity, as environmental economist Todd BenDor makes clear when he points to regulations requiring the placement of silt fences in new subdivisions along waterways.

“They’re supposed to prevent erosion, but they often fail or are put in the wrong places,” he says. “Markets can simply enact a limit on erosion, allowing the landowner the freedom to be creative and efficient in any way they see fit in order to meet that limit.”

Done right, environmental markets can replace overly prescriptive regulations, but they still require government oversight and regulation.

“Markets are entirely reliant on strong monitoring, verification and enforcement of limits,” says BenDor. “Provisions must be made to ensure that, but in reality it’s often a problem.”

6. Restoration stimulates rural economies

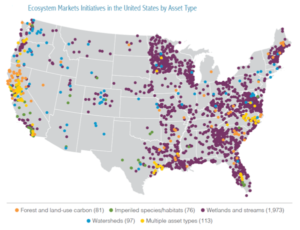

In 2015, BenDor published a study called “Estimating the Size and Impact of the Ecological Restoration Economy,” which found restoration businesses in all 50 states. California had the most, but four “red” states filled out the top five: Virginia; Florida; Texas; and North Carolina. Last place went to North Dakota.

In 2015, BenDor published a study called “Estimating the Size and Impact of the Ecological Restoration Economy,” which found restoration businesses in all 50 states. California had the most, but four “red” states filled out the top five: Virginia; Florida; Texas; and North Carolina. Last place went to North Dakota.

By their very nature, restoration projects are in rural areas, and a study by Cathy Kellon and Taylor Hesselgrave of EcoTrust found that Oregon alone had more than 7,000 watershed restoration projects, which generated nearly 6,500 jobs from 2001 through 2010. Many of those jobs went to unemployed loggers.

“The jobs created by restoration activities are located mostly in rural areas, in communities hard hit by the economic downturn,” report authors wrote. “Restoration also stimulates demand for the products and services of local businesses such as plant nurseries, heavy equipment companies, and rock and gravel companies.”

7. It’s been mapped

Last year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of Environmental Markets, together with Ecosystem Marketplace publisher Forest Trends and the Environmental Protection Agency, published an online Atlas of Ecosystem Markets, which you can access here.

8. The jobs are robot-proof

Environmental regulations didn’t kill coal; natural gas and renewables did. Regulations didn’t stifle the western oil boom, either; that was low energy prices. Even if Trump & Co. do prop-up the coal sector, jobs won’t go to people; they’ll go to machines, which took most of the jobs (PDF) America lost in the last decade.

BenDor’s research shows restoration jobs are evenly divided between white-collar planners, designers and engineers and the green-collar guys doing the actual earth moving and site construction.

Almost all involve time in the great outdoors, and they can’t be exported or done by robots.

9. The jobs are cost-effective

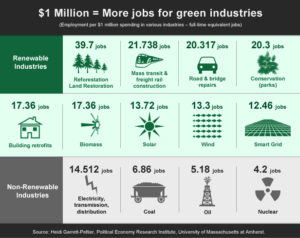

Because restoration work is labor-intensive, the money goes to people instead of machines, and every $1 million invested generates 33 jobs on average. Every $1 million invested in oil, on the other hand, generates 5.2 jobs per $1 million invested. In coal, the figure is 6.9 jobs.

10. It doesn’t stifle business

Some industry groups claim the Endangered Species Act blocks development, but researchers reviewed 88,000 consultations between 2008 and 2015 and found that no projects had been stopped or even changed in a major way to protect habitat.

Even proponents of the system concede, however, that the permitting process is slow and tedious.

11. It can be improved

While the FWS administers credits for mitigation of endangered species, the Army Corps of Engineers approves mitigation credits for streams and wetlands, and they’re notoriously underfunded.

This leads to long and costly delays, according to unpublished research that BenDor conducted with Daniel Spethmann of Working Lands Investment Partners and David Urban of Ecosystem Investment Partners.

Delays are so costly, they argue, that companies in the restoration sector might be better off paying fiftyfold higher permitting prices that would give the agencies the staff needed to properly process permits, akin to expedited building permits, rather than paying banks the interest on loans for land where environmental improvements are being held up.

Featured photo of rain garden courtesy of Philadelphia Water Department.