In the year following Hurricane Katrina disaster in August of 2005, I (Storm Cunningham) was was brought down to New Orleans four times by a variety of organizations: the non-profit City-Works, the University of New Orleans, the University of Louisiana, and the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), which retained me do a public talk in the city council chambers.

In each case, they were seeking insight into better ways to rebuild their lovely city. As a result, I met with a wide variety of public and private leaders, often with the great community advocate Ray Nichols as the middleman.

One potential project that came up over and over, especially when African-American leaders were in the room, was the revitalization of the North Claiborne Avenue corridor.

When U.S. urban highway planners in the 60s and 70s were seeking routes for new highways, they had an unerring eye for low-income immigrant and/or ethnic minority neighborhoods.

It didn’t seem to matter how vibrant or historic the neighborhood might have been: if darker skin, foreign languages and/or emptier wallets were common, planners inevitiably declared it “blighted” so they could have their way with it.

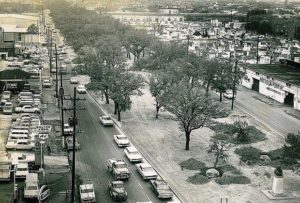

North Claiborne Avenue was one such victim. A beautiful boulevard whose median boasted over 300 ancient live oak trees, as well as over 300 black-owned businesses.

It was the beating heart of the local African-American culture, and a destination for vacationing southern blacks in many states.

“It was drop-dead gorgeous, an oasis, a place to meet friends,” says Jessie Smallwood, 85, in a Next City article by Katy Reckdahl. “You were underneath trees. You knew people a block over.”

Planners demolished it and replaced it with an elevated concrete monstrosity of a highway that divided and devitalized the area and largely stopped that heartbeat.

For nearly a half-century, people have mourned how this raised section of federal highway sliced through more than two miles of the city’s historically black neighborhoods, dooming Claiborne Avenue’s thriving business corridor.

Today, the outermost pillars along this stretch of Claiborne Avenue are painted to look like trees, while about 40 of the inner pillars are the canvas for original paintings by some of the city’s finest artists. They were created as part of a project called “Restore the Oaks,” spearheaded by painter and teacher Richard Thomas through the city’s New Orleans African American Museum of Art and Culture.

The result is an open-air art gallery that reflects the live oaks, people and culture of Claiborne Avenue, Tremé, the 7th Ward and New Orleans as a whole.

Those strolling under the elevated highway on ground-level asphalt can walk past both Charlie Johnson’s and Charlie Vaughn’s images of Big Chief Allison “Tootie” Montana, the famed Black Masking Indian who lived a few blocks away. They can view a detailed image of a typical jazz funeral, painted in by Nat Williams, who works as a barber nearby.

The recently released Claiborne Corridor Cultural Innovation District Master Plan is rooted in the ideas and desires of residents.

Informed by a series of 11 design charrettes held with residents and architects from May 2017 to February 2018, the master plan sets out to beautify and revitalize the corridor. It hopes to increase jobs and economic stability through innovations such as a marketplace built with green infrastructure, which will run within a 25-block segment of the corridor.

Here’s the Cultural Innovation District Community Vision Statement:

“We, the residents of the Claiborne neighborhoods, are at the heart of the future Claiborne Avenue corridor. In that future, we celebrate our culture and family traditions where our historic neighborhoods are safe and affordable for all who want to live here.

“We, the residents of the Claiborne neighborhoods, are at the heart of the future Claiborne Avenue corridor. In that future, we celebrate our culture and family traditions where our historic neighborhoods are safe and affordable for all who want to live here.

Our neighborhood streets, community parks, and the Lafitte Greenway fill with family gatherings and the music and parades of second line and Mardi Gras Indian traditions.

Claiborne, St. Bernard, Esplanade Avenues, Broad and Canal Streets, and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard thrive with locally owned businesses, affordable goods and services for daily living, reliable employment for residents, and positive learning experiences for neighborhood youth.

Quality public transit is convenient, reliable, clean, and affordable with a broad reach to jobs and neighborhoods city-wide. Traffic even on business streets yields to bicyclists, crossing pedestrians, and the festivities that sometimes spill out from local cross streets.

Quality public transit is convenient, reliable, clean, and affordable with a broad reach to jobs and neighborhoods city-wide. Traffic even on business streets yields to bicyclists, crossing pedestrians, and the festivities that sometimes spill out from local cross streets.

The Medical District provides affordable healthcare and living-wage jobs. New industries in the city attract workers who support Claiborne Corridor businesses and respect and appreciate what we value in our communities.”

Mural photos are by Linda Pfeiffer / University of Wisconsin – NOLA.

See full Next City article by Katy Reckdahl.