On April 12, 2019, the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum—the birthplace of restoration ecology in the United States—was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

This news is of great personal interest to me (Storm Cunningham), as it was the science of restoration ecology—and the practice of ecological restoration—that led to my first book, The Restoration Economy, which I started writing in 1996, and was published in 2002. One of my first professional memberships related to restorative development was in the then-newly-formed Society for Ecological Restoration.

This news is of great personal interest to me (Storm Cunningham), as it was the science of restoration ecology—and the practice of ecological restoration—that led to my first book, The Restoration Economy, which I started writing in 1996, and was published in 2002. One of my first professional memberships related to restorative development was in the then-newly-formed Society for Ecological Restoration.

National Register designation provides access to certain benefits, including qualification for grants and for rehabilitation income tax credits, while it does not restrict private property owners in the use of their property.

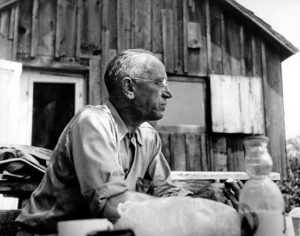

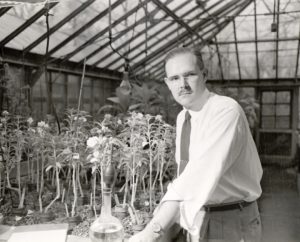

The listing recognizes the Arboretum’s historic significance for pioneering developments in conservation science and ecological research led by influential conservationists like John Curtis and Aldo Leopold.

In Wisconsin, the Arboretum is recognized because of its landscape architecture, education and research, architectural elements, and its hosting of a Civilian Conservation Corps camp in the 1930s.

The Arboretum joins 70 other properties around campus already listed in the historic register. Listing in the register extends protection to buildings and structures that ensures their historic significance will be considered as any changes are made. The National Park Service, which oversees the register, approved the listing of the Arboretum in March.

Protection helps “maintain the ability of the property to tell its story,” says Daniel Einstein, the historic and cultural resources manager for Facilities Planning and Management, who assisted with the nomination of the Arboretum to the register.

The Arboretum was dedicated in 1934. Two years later, Curtis, Leopold and others designed and planted the first restored prairie in the world, now known as Curtis Prairie. Along with other projects at the Arboretum, Curtis Prairie established that restoring an ecosystem to an earlier state is an effective way to study and preserve endangered habitats.Many of those restored habitats were built with the assistance of workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps, part of the Great Depression-era New Deal work programs, between 1935 and 1941. Corps workers also helped build roads, buildings and trails around the Arboretum. Original CCC buildings still stand on the property.

Madison architectural historian Elizabeth Miller wrote the Arboretum’s nomination for listing in the register. Across a career spanning more than 30 years, Miller has written the nominations for several historic campus properties.

She first assessed the Arboretum for its eligibility back in 2003. Miller is now working to nominate the Arboretum to be a National Historic Landmark, a rarer designation that bestows greater protection than listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Existing national landmarks on campus include North Hall—the first university building—and Science Hall.

To be listed in the register, a property has to be at least 50 years old and meet at least one of the following criteria: significance in architecture; association with a person of importance; archaeological potential; or significant events in its history. History is a broad area of significance with many categories, including education and conservation.

The nomination is first sent to the Wisconsin Historical Society for evaluation before going to the National Park Service for final approval.

“It’s been a long time and I’m just so thrilled the Arboretum is listed in the National Register,” says Miller, who recalls visiting the Arboretum as a schoolchild and now lives nearby.

“It’s just the most amazing property,” she added. “It absolutely deserves it.”

In addition to Curtis Prairie (begun 1936), the Arboretum also maintains other examples of the nation’s oldest collection of ecologically restored ecological communities including Teal Pond (begun 1940), Gallistel Woods (begun 1941), Greene Prairie (begun 1943), and Wingra Woods (begun 1943).

Research and experimentation carried out at the Arboretum beginning in 1934 pioneered and refined techniques and procedures for restoring and managing many different ecological communities from Wisconsin forests, prairies, and wetlands. These ecosystems are found not only in Wisconsin but in many areas across the country.

Methods developed at the Arboretum have been disseminated through technical and popular journals and through the academic and professional careers of the many graduates of the University of Wisconsin in conservation-related fields who have studied in the Arboretum.

The ecological communities themselves have served as models, inspiring other ecological restoration projects (especially prairies), and have provided seeds to other arboreta and botanical gardens worldwide through the seed exchange program (from 1952 into the 1990s).Ecological restoration and ecologically restored ecological communities were slow to gain approval from conservationists, whose goals were erosion control and sustainable productivity of natural resources, and from preservationists, who sought to preserve pristine natural areas.

However, the modern environmental movement of the late 1960s, with its dual aims of preserving natural areas and healing degraded land, brought ecological restoration into the mainstream in the 1970s.

It is now regarded as “best practice” in land management for both restored and natural landscapes. Governmental agencies employ ecological restoration to improve and maintain parks, recreational and natural areas. Ecological restoration is utilized for mitigation projects mandated by the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) and similar federal and state legislation.

Increasingly, landscape architects use ecological restoration to re-create native plant communities on small sites, from corporate properties to school grounds, to back yards. The ecologically restored ecological communities at the Arboretum and the research their development has generated have provided a model and a proving ground for ecological restoration, making the Arboretum the catalyst for transforming ecological restoration into best practice in land management nationwide.

The register is the official national list of historic properties in America deemed worthy of preservation and is maintained by the National Park Service in the U.S. Department of the Interior. The Wisconsin Historical Society administers the program within Wisconsin. It includes sites, buildings, structures, objects and districts that are significant in national, state or local history, architecture, archaeology, engineering or culture.

The Wisconsin Historical Society, founded in 1846, ranks as one of the largest, most active and most diversified state historical societies in the nation. As both a state agency and a private membership organization, its mission is to help people connect to the past by collecting, preserving and sharing stories.

Featured photo by Jeff Miller/UW-Madison shows native prairie plants surround a commemorative rock marking Curtis Prairie at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum during a summer morning on Aug. 15, 2013. All other photos courtesy of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum.

See University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum website.