The single most crucial component in rejuvenating decaying urban areas around the world is private sector participation, according to a report released today from the World Bank and the Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) during the World Cities Summit taking place in Singapore this week.

“Urban regeneration projects are rarely implemented solely by the public sector. There is a need for massive financial resources that most cities can’t meet,” said Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez, Senior Director for the World Bank’s Social, Urban, Rural and Resilience Global Practice. “Participation from the private sector is a critical factor in determining whether a regeneration program is successful – programs that create urban areas where citizens can live, work, and thrive.”

Every city has pockets of underused land or distressed urban areas, most often the result of changes in urban growth and productivity patterns. In developing countries, which are absorbing 90 percent of the world’s urban population growth, decaying inner cities are home to an increasing number of poor and vulnerable citizens. These areas marginalize and exclude residents, and can have a long-term negative effect on their upward mobility.

Regenerating Urban Land: A Practitioner’s Guide to Leveraging Private Investment looks at regeneration programs from eight cities around the world – Ahmedabad, Buenos Aires, Johannesburg, Santiago, Singapore, Seoul, Shanghai, and Washington, DC – documenting the journeys they have faced in tackling major challenges in this area.

Building on the experience of cities from different regions around the world, the report looks at projects for inner cities, former industrial or commercial site, ports, waterfronts, and historic neighborhoods. While the cases vary in many aspects, what they have in common is significant private sector participation in the regeneration and rehabilitation of deteriorating urban areas.

The report singles out successful policy and finance tools in each city case study, and points out issues and challenges the city faced during the process. It identifies four distinct phases for successful urban regeneration: scoping, planning, financing, and implementation. Each phase includes a set of unique mechanisms that local governments can use to systematically design a regeneration process.

For example, in Singapore, the polluted Singapore River was no longer used for trading activities as large-scale container ports gained prominence.

“Capitalizing on the Singapore River’s historical importance and potential for redevelopment, the government launched a transformational program that preserved cultural heritage, improved the environment, and opened the area for recreational pedestrian use. Similar efforts elsewhere can rejuvenate cities and regional economies,” said Jordan Schwartz, Director of the World Bank’s Infrastructure & Urban Development Hub, based in Singapore.

Yet there is no “one size fits all” approach when looking for solutions to cities’ declining areas. The report stresses that while the tools presented in the report yielded successful results in many cities around the world, no one solution is universally applicable to all cities and situations. The report also emphasizes that with strong political leadership, any city can start an urban regeneration process, but the successful use of land-planning and finance tools depend on sound and well-enforced zoning and property tax systems.

“No two cities are alike, so to meet this challenge, the World Bank created an online decision tool, based on the specific issues the city faces and its current regulatory and financial environment,” said Rana Amirtahmasebi, author of the report. “Local governments can use the information curated in this report to begin to reverse the process of economic, social, and physical decay in urban areas, moving toward the sustainable, inclusive development of their cities.”

Illustrating the transformation, other case studies from the new report include:

Santiago, Chile lost almost 50 percent of its population and 33 percent of its housing stock between 1950 and 1990. But the city turned this around, using a national housing subsidy to specifically target the repopulation of the inner city. The private investment reached USD 3 billion throughout the life of project, stimulated by a USD 138 million subsidy.

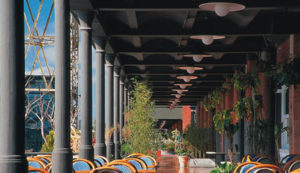

Buenos Aires, Argentina found itself on the verge of becoming unsustainable, when urban sprawl moved away from downtown leaving prime waterfront land, with significant architectural and industrial heritage, vacant and underused.

To tackle this problem, the city used a self-financing urban regeneration initiative in Puerto Madero to redevelop the unused 170-hectare land parcel to an attractive mixed-use waterfront neighborhood. The total investment reached USD 1.7 billion, with USD 300 million invested by the city through the sale of land.

Seoul, Republic of Korea experienced a major decrease in residential and commercial activity in its downtown, where small plots, narrow roads, and high land prices made development too costly. From 1975 to 1995, Seoul lost more than half its downtown population, while substandard housing for mostly squatters and renters was more than twice the city’s average.

Seoul launched the Cheonggyecheon revitalization project to redevelop an 18-lane elevated highway into a revitalized stream with green public space totaling 16.3 hectares, dramatically increasing real estate values and the variety of uses for the downtown areas.

Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India saw the closure of mills along the Sabarmati Riverfront, which caused unemployed laborers to form large informal settlements along the riverbed, creating unsafe and unclean living areas and reducing the flood management capacity.

In response, the city created a development corporation to reclaim 200 hectares of riverfront land on both sides and paid the project costs through the sale of 14.5 percent of the reclaimed land, while the rest of the riverfront was transformed into public parks and laborers resettled through a national program.

In the 18-square kilometer inner city of Johannesburg, South Africa, a series of targeted regeneration initiatives achieved a decline in property vacancy rates from 40 percent in 2003 to 17 percent in 2008, and a similar jump in property transactions.

Since 2001, for every rand (R) 1 million (about USD 63,000) invested by the Johannesburg Development Authority, private investors have put R 18 million into the inner city of Johannesburg, creating property assets valued at R 600 million and infrastructure assets valued at R 3.1 billion.

Photo of Puerto Madero, Argentina featured at top of article courtesy Adobe Stock Photos

Photos of Johannesburg and of Santiago, Chile via Adobe Stock Photos