Even if global average temperature increases are limited to below 2°C, there will still be serious climate impacts. Since pre-industrial times, we have witnessed a global average temperature increase of 1.1°C, while ocean acidity has increased by 26%. An increasing number of destructive weather-related extreme events are taking place.

The intensity and scale of the wildfires that affected Australia and California in 2019-20, for example, were attributed to climate change.

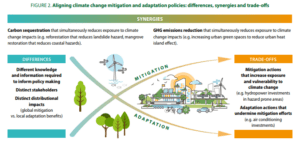

Until now, efforts to mitigate and to adapt to climate change have been led by distinct policy communities, building on specific knowledge and information, and mobilizing different stakeholders to address distinct technological and distributional challenges.

However, the issues of mitigation and adaptation are linked and when addressed jointly, their impact and effectiveness can be reinforced.

The G20 leaders recently acknowledged “the importance of fostering synergies between adaptation and mitigation, including through nature-based solutions and ecosystem based approaches”. National climate policies also reflect this synergy, such as in the UK’s Adaptation Communication issued in December 2020, which highlights the allocation of EUR 700 million from the Nature for Climate Fund to nature-based solutions that promote synergies between mitigation and adaptation.

Where can we find synergies between climate adaptation and mitigation measures?

Linkages and synergies can be found in a number of policy areas, including forestry, agriculture, water and urban planning:

- Forest conservation can enhance the sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere, while helping to reduce the impact of extreme precipitation events (e.g. floods). Successful reforestation examples include the Sloping Land Conversion Programme and the Reforestation Programme in China, which have managed to increase carbon sequestration and enhance soil retention;

- Agricultural soil improvement measures help increase the amount of carbon sequestered, while rendering crops more resilient to extreme weather (such as droughts). The Canadian climate policy framework explicitly aims to increase the carbon storage capacity of agricultural soils to partially offset the sector’s GHG emissions;

- Urban green measures, such as parks and green roofs, help mitigate GHG emissions from energy use by lowering the urban heat island effect. At the same time, vegetation and permeable grounds increase water absorption capacity, thereby significantly reducing the risk of urban flooding. The French cities of Paris and Seine-Saint-Denis have developed measures that encourage ecosystem restoration, obtaining significant improvements in flood management; and

- In the context of water management, nature-based solutions such as wetland restoration and mangrove rehabilitation can enhance their carbon sink size, while at the same time offering a natural defense against water-related risks. The UK actively supports peatland restoration as natural flood management measures contributing to both mitigation and adaptation.

What are the potential trade-offs between mitigation and adaptation objectives?

While harnessing the synergies between adaptation and mitigation offers important opportunities to enhance policy effectiveness, trade-offs need to be considered, both between mitigation and adaptation objectives, as well as among climate and other environmental policy priorities.

For example, while hydropower dams mitigate climate change by supporting the production of clean energy, they may exacerbate the impacts of extreme weather events downstream and contribute to local ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss. Similarly, the increased use of desalination plants are an important adaptation measure to cope with water scarcity, but they may increase energy demand from potentially GHG-intensive sources of energy production.

Furthermore, certain nature-based solutions rely on ecosystem services that are themselves subject to climate change. For example, rising temperatures can alter the stability of forests (e.g. through wildfires), thus affecting their capacity to store carbon. Similarly, between 70% to 90% of coral reefs – a fundamental ecosystem for coastal protection – are set to disappear if global surface temperatures increase by 1.5°C and more than 99% of corals would be lost if temperatures increase by 2°C.

Exploring opportunities for win-wins can make important contributions to the race against climate change.

In its future work, the OECD will continue to assess adaptation-mitigation linkages and will help countries identify and manage trade-offs, such through its work on managing extreme wildfires and coastal risk – both are areas in which linkages hold a significant potential to reinforce each other in achieving resilience to climate change.

Photo of Los Padres forest fire in California via Pixabay.

This article by Catherine Gamper and Mikaela Rambali of the OECD Environment Directorate originally appeared on the OECD blog site. Reprinted here (with minor edits) by permission.