Engineers often have to deal with conflicting constraints. For instance, an aircraft designer might be told that a new airplane must be both faster and more fuel efficient. Some will tell you that resolving conflicting constraints is the primary purpose of engineering.

But it’s not just engineers who are asked to achieve apparently-contradictory goals. Vendors of all kinds often tell customers, “Faster. Better. Cheaper. Choose two.” And so it is in cities worldwide.

Some say that the primary purpose of local government is to resolve conflicting constraints, such as faster economic growth with increased environmental health.

Public leaders are increasingly told to boost property values, tax revenues and quality of life (revitalization) without excessive or unfair displacement of long-time residents (gentrification).

As cities develop more expertise in restorative development and neighborhood revitalization, the issue of gentrification becomes ever-hotter. (Before we go any farther, I should point out that this article isn’t meant to be an in-depth analysis of gentrification’s causes and manifestations. I only wish to draw attention to some of the dynamics that seem to be impeding progress on the issue.)

The controversy has become so widespread now, that it’s become quite common to hear ill-informed people here in the USA using “gentrification” and “revitalization” as if they were synonymous. They are not. That’s like saying “high-speed car crash” is the same as “transportation”. When gentrification is the result, the underlying planning assumption is usually “better people make better neighborhoods”, with “better” being defined as “wealthier”.

Equitable revitalization is a better neighborhood with (mostly) the same neighbors. I say “mostly” because poor neighborhoods often benefit from increased income diversity. In such cases, the difference between revitalization and gentrification becomes a matter of degree.

If we do something good badly–or do too much of it–that does not make the good thing bad. The failure is in our implementation. Unnecessarily painful gentrification is simply revitalization done badly. Revitalization should lift people up, not push them out.

If one defines gentrification as a rise in incomes and quality of life, then it’s safe to say nobody complains when gentrification comes to a neighborhood, provided they are participants, not just onlookers.

The affordable housing crisis being experienced in most revitalizing cities these days is normally perceived as a shortage of low-end residential units. But it can also be seen as inequitable economic growth, whereby the benefits of revitalization aren’t flowing to those who need it most. So, is it really an affordable housing shortage, or is it a shortage of well-paying jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities? Or both?

In recent years, Denver, Colorado has done a wonderful job of revitalizing its downtown (as reported several times in REVITALIZATION, such as here and here), and they’ve used light rail to spread that revitalization across the metro region.

As a result, residential rents have suddenly skyrocketed from below the national average to 12.6% above average. “Before we’ve realized it almost, we’re a high cost housing city,” says Ismael Guerrero, director of the Denver Housing Authority. “We’re new to that club, but we’re clearly there, because the wages haven’t kept up.”

Stimulating property value enhancement without anticipating and making some attempt to ameliorate the predictable negative impacts on lower-income families indicates a lack of concern by public leaders. These dynamics are universal: they should take no one by surprise. But Ismael isn’t to blame: revitalization is a systemic process that can only be addressed at higher levels of public management than a housing authority.

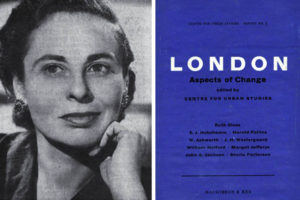

British sociologist Ruth Glass coined the term “gentrification” in her book London: Aspects of Change (1964). She was referring very specifically to the displacement of lower income residents with higher higher income residents.

British sociologist Ruth Glass coined the term “gentrification” in her book London: Aspects of Change (1964). She was referring very specifically to the displacement of lower income residents with higher higher income residents.

Although the term derives from the “landed gentry”, the “displacers” in these regenerating London neighborhoods were usually only middle class.

So, when the middle class is displaced by the upper class, should that too be called gentrification?

The sad state of affairs is that American cities and neighborhoods that are dramatically revitalizing almost always experience gentrification.

Gentrification, as I’m using it here, is the traumatic disruption of long-time residents’ lives, often leading to displacement. It’s caused by rapidly-rising property values, which raises property taxes and rents, meaning that both low-income homeowners and low-income renters are forced from their homes.

But wait: isn’t increasing the value of property–and boosting public revenues–the whole goal of revitalization? No, it isn’t.

That’s the whole goal for most private redevelopers (as opposed to developers, who do sprawl projects), and that’s fine: that’s a market force that can be harnessed for revitalizing capital.

But if market forces are the only forces at work, then there’s a failure of government.

In the emotion-packed, fact-free, money-driven chaos that passes for political dialog in the United States, Americans seem to have forgotten the role of government.

It’s the job of the government (together with the justice system) to watch over the welfare of their citizens.

That means:

- raising the quality of life for all;

- increasing job and business opportunities for all;

- boosting health, safety, and social justice for all;

- restoring natural resources, reactivating abandoned properties, rehabilitating heritage, and regenerating the economy for all;

- constantly renewing, repurposing, and reconnecting the community’s assets to keep it vibrant and relevant in a changing economy.

All of those factors together comprise the definition of true revitalization. That’s far beyond the remit of real estate investors.

The simple fact of the matter is that traumatic, unjust gentrification is preventable. What’s more, it’s easily preventable. Yes: it’s a complex problem. But the solution is dead simple: the government simply has to WANT to prevent it.

Once that desire is established, the tactics and strategies that can produce revitalization with a minimum of trauma and dislocation are numerous. Desire is the key. Add social justice to your local revitalization vision, and it will flow through into your strategy, policies, plans, programs, projects, and partnerships.

I’ve been discussing these solutions in my talks and workshops for most of the past decade. I documented two simple solutions that were actually put in place by conscientious private redevelopers (who stepped in to fill the gap left by unconcerned local government officials) in my 2008 book from McGraw-Hill: Rewealth. One used TIF to ensure that any increased taxes came back to those communities in the form of neighborhood improvements. The other set up a non-profit fund using a surcharge on the sale of new residences, which refunded any increase in property tax paid by the long-established residents.

I also address the creation of effective strategies in my new Resilience Strategy Guide.

Attracting higher-income folks to a poor neighborhood is exactly what local leaders are trying to accomplish when they launch revitalization initiatives. What’s more, communities are living systems that change as they evolve. Just as species migrate to different environments as ecosystems evolve over time, so too do residents change neighborhoods as cities evolve.

None of this is evil or racist, and it’s not really those dynamics that people are objecting to when they throw around that weighted word “gentrification”. The real problem is that both governments and private developers often lack the sensitivity and humaneness to ensure that these changes happen in a way that minimizes suffering and unnecessary displacement.

So the solution is more in changing HOW we do revitalization, not in changing its basic dynamics. Revitalization is change, and change is inevitable. As one wag said “Cities change. Get over it.” But callousness isn’t inevitable. It can easily by avoided by greater awareness and more caring about each other. Kinder, gentler redevelopment, if you will.

In a personal communication, Aksel Kargård Olsen, Senior Planning Analyst at the San Francisco Bay area’s Metropolitan Transportation Commission told me “I think this is generally true: all manner of things are policy failures at their core. Income inequality? Sure, folks like to blame greed as if it were an anomaly in markets, the just once in a blue moon occurrence requiring swift and public denunciation. Markets do what markets do, which is why we have policies shaping them in the first place. Gentrification and its expressions is a great example of that.”

Does this mean that private redevelopers are blameless? Of course not. Some are brazenly insensitive to the needs of lower-income residents, especially ethnic minorities. The modus operandi of others is to buy influence on the city council, sometimes to the point of not just getting their own project approved, but to enact unhealthy changes to zoning, building codes, and development incentives that undermine the community for decades. That’s just who they are. But when they get their way, it counts as a failure of government.

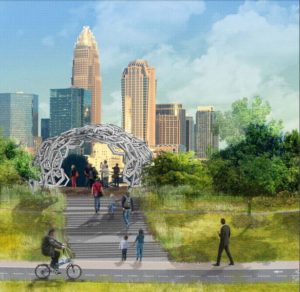

Charlotte, North Carolina is building massive greenway system that revitalizing neighborhoods throughout the greater area. They are basically trying to produce the High Line Effect with a metropolitan area scope. For those new to the world of urban redevelopment, a bit of background about the High Line follows.

Excerpt from the Resilience Strategy Guide about the High Line:

Just look at the High Line Park. New York City planned to spend millions of dollars demolishing this defunct elevated railway. Keeping the ugly relic made no sense, until two local citizens–Robert Hammond and Josh David–envisioned repurposing it as a linear park.

Redevelopment along High Line in 2014.

Photo by Storm Cunningham.

That unleashed funding for renewing the structure as a beautiful green pedestrian space, which more than doubled nearby real estate values. In its first decade, the High Line generated $2.2 billion in new economic activity. The city expects over $1 billion in increased tax revenues over the next 20 years. It’s visited by over 5 million people annually, making it the city’s 2nd most visited cultural attraction.

But that’s not all. By reconnecting neighborhoods on the lower west side of Manhattan with the Hudson Rail Yards, the High Line enabled the city to do something they had envisioned for decades: cap and develop the space above the rail yards.

Sign on the High Line.

Photo by Storm Cunningham.

This is now happening: the $20 billion Hudson Yards mixed-use redevelopment is the largest real estate transaction in New York City history. That’s a 3Re-based strategy at work.

Here’s the key lesson from the High Line: Repurposing, renewing, and reconnecting are each powerful and effective on their own. Many communities have been revitalized using just one of these tactics. But the magic occurs when all three are combined to reinforce each other, thus forming a true revitalization strategy.

Charlotte wants their greenway system to produce the revitalizing power of the High Line,. The article excerpted from the Charlotte Observer below asks whether they can do it without the notorious gentrification the High Line created on the lower West Side of Manhattan.

Excerpt from Charlotte Observer article by Ely Portillo:

As Charlotte looks to grow its greenway system, especially through economically distressed areas north of uptown, the benefits are clear: Higher property values, more access to transportation alternatives and exercise, an incentive for developers to build.

What’s less clear: How to stop such investments from spurring gentrification and displacement of residents who already live there.

“If just left to the market forces, it’s very likely that displacement and gentrification would occur,” said Kyle Vangel of HR&A Advisors. “You have to be proactive to preserve and create affordable housing in certain corridors.”

The $35 million Cross Charlotte Trail is expected to open over the next decade, running from Pineville through uptown and north to Cabarrus County, and its final budget is expected to be higher. It’s the city’s most ambitious greenway project under development, meant to span 26 miles and connect existing greenways.

If you want to see how a greenway can transform an area, look at the Little Sugar Creek Greenway near uptown. That’s where Mecklenburg County uncapped a paved-over creek and built a walking and biking trail, helping to spur developments such as the Target, Trader Joe’s, and condominium-anchored Metropolitan.

Beth Poovey of LandDesign says, “People will pay a premium to live along these corridors,” she explained, noting that conservative estimates put rent and commercial prices 5 to 15 percent higher in such areas. There’s a corresponding increase in for-sale prices as well.

That generates more property taxes and can revitalize a blighted area.

Excerpt from the Executive Summary of the master plan for the Cross Charlotte Trail:

The City of Charlotte is partnering with Mecklenburg County to build a 26-mile trail and greenway system that will stretch from Pineville, through uptown Charlotte, and on to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte campus and the Cabarrus County line.

Called the Cross Charlotte Trail, when complete, people will be able to use this trail to travel continuously across the city and county to connect with many destinations including parks, employment and retail centers, neighborhoods and more.

About 98,000 jobs and 80,000 residents currently are within a half-mile of the proposed trail route. As Charlotte-Mecklenburg has grown, so has residents’ demand for greater connectivity through an expanded transportation-by-trail network within our community. City and county leaders have long advocated the far-reaching benefits of investing in trail infrastructure. In 2014, residents demonstrated their strong support for an extensive new trail system by approving the first $5 million in City bonds to begin development of the Cross Charlotte Trail. Hopefully, some of that money will be spent on proactive approaches to reducing displacement along that corridor.

One organization that’s helping cities do exactly this is Transportation For America (TFA), which recently prepared a report for Nashville, Tennessee. Nashville is on the verge of adding much-needed, high-capacity transit to a struggling area called the Nolensville Pike corridor.

As soon as the transit project is approved, real estate speculators will swoop in, as confidence in the revitalized future of the corridor sinks in. Those speculators can seriously undermine the community’s revitalization vision, so anti-gentrification controls need to hardwired into all entitlements and incentives (see below).

As soon as the transit project is approved, real estate speculators will swoop in, as confidence in the revitalized future of the corridor sinks in. Those speculators can seriously undermine the community’s revitalization vision, so anti-gentrification controls need to hardwired into all entitlements and incentives (see below).

The tactics and strategies outlined in TFA’s report—called Envision Nolensville Pike II—are applicable to any city that wishes to add transit and stimulate revitalization in a more-inclusive, sensitive manner.

Here’s an excerpt from TFA’s description of the report:

“Our detailed analysis offers specific recommendations to help decision-makers in the city and region make the corridor safer for everyone, improve the economic prospects (and equity) of the area, and provide new opportunities for adding housing and jobs — all while avoiding displacement of the vital communities of residents and businesses that call the Pike home. Now is the time to take proactive measures to prevent displacement and preserve the unique identity of the area, while simultaneously making Nolensville Pike safer for everyone, improving the economic prospects (and equity) of the area, and providing new opportunities to add housing and jobs. By tackling these issues now, before development pressures have driven large-scale business closures or widespread displacement of current residents, the region will have the best chance of seeing its future growth occur in an equitable way, shared by all.”

Maybe the most promising “new” trend in long-term solutions to the gentrification/affordable housing challenge is the rise of community land trusts. We’ve addressed CLTs several times here in REVITALIZATION, such as here, here, and here.

Community land trusts have been around a long time in various forms. One of the best known is in Burlington, Vermont, where a then-little-known mayor named Bernie Sanders helped make it possible by championing the idea of land trusts in the 1980s. Community land trusts allow the residents of rapidly-revitalizing neighborhoods to own and manage real estate for perpetual public benefit.

As community land trust expert David Freed told me in an email, “A new way of thinking and talking about measures of success of anti-displacement strategies is needed. Community land trusts are based on development AND preservation of affordable community assets in perpetuity. This is quite a radical shift in how redevelopment success is measured: set-asides of affordable housing units in one-off developments or comprehensive revitalization isn’t a sufficient measure of anti-displacement. The Burlington, Vermont community land trust works, I believe, because priority for public dollars for housing goes to developments that assure permanent affordability. This priority for the use of affordable housing dollars began with the City and then was embraced by the State.”

Taking the affordable housing challenge seriously isn’t just a matter of good governance and social/economic justice: it can save your career. Look at what happened with the Atlanta Beltline, which is the best thing that’s happened to that notoriously badly-planned metro area in a long, long time. Ryan Gravel’s original vision for the Beltline (which he formulated as a grad student at Georgia Tech) made affordable housing a key component of the plan, which repurposes old rail lines into pedestrian and bicyclist trails to green and reconnect Atlanta’s inner-ring neighborhoods. As a result, Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. (ABI)–the managing entity–promised some 5,600 units of affordable housing.

Almost a year after Gravel and Nathaniel Smith resigned from the ABI board in protest of the way developers had co=opted the Beltway dream to maximize their profits, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation revealed that “halfway to the Beltline’s scheduled completion, it has only funded 785 affordable homes, more than 200 of which remain under construction.”

Shortly thereafter, on July 26, 2017, while speaking at the Atlanta Commerce Club, Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed indicated that a leadership change was in the making at ABI. In response to an attendee’s question about affordable housing along the BeltLine, Reed said there was going to be more funds available to improve equity along the corridor. Then, in a comment obviously surprising Paul Morris, the then-current CEO of ABI (who was sitting in the back of the room), Reed said “You’ve got to have a leader of the BeltLine that is committed to affordability as a first thought and not an after-thought.”

That could be said of public leaders nationwide, and all around the world.

The good news is that there’s a simple mechanism by which affordable housing and other inclusive, equitable practices can be “baked into” the redevelopment process: attach these anti-gentrification elements to any funding (such as TIF) or other incentives offered by the city, county, or state. The state, for instance, could build it into their historic tax credits for residential (and commercial) projects, for instance. I added “or commercial” because gentrification isn’t just about residents: long-standing local businesses also get pushed out.

The best approach would probably be a point system, whereby developers need to accumulate a certain number of “fairness” points to qualify for the incentive. That gives them the flexibility they need. Tactics that are too arbitrary (such as a fixed ratio of affordable-to-market-rate units, can undermine the area’s revitalization by making too many projects financially unfeasible.

And speaking of TIF, here’s another idea: One way to discourage the short-term speculators who create a lot of the displacement is by taxing the increase in residential property values. This could be called “tax increment stabilization” (TIS), a complement to tax increment financing (TIF).

The purpose of TIF is catalyze the redevelopment in the first place. The purpose of TIS would be to moderate property values, and help ensure that increases are driven by “real” redevelopment, rather parasitic speculation.

TIS could be made even more effective if the proceeds of the tax in this “TIS District” were earmarked to directly address affordabilty. The money could fund Housing Choice Vouchers, or could be offered as a credit towards the increased tax bills of long-term residents.

Maybe the simplest way to speed the creation of solutions is to stop using the term “gentrification”. A word is useless if there isn’t broad concensus on its meaning. In this case, the spectrum of meanings runs from desirable (revitalization) to undesirable (involuntary displacement).

The problem is displacement, so let’s stop confusing people and just call it that: displacement. Here’s an article about displacement that never uses the term “gentrification”, by way of example.

Potential solutions are numerous. What’s in short supply is a desire for those solutions on the part of public leaders. That’s the root of the problem.

About the Author:

Storm Cunningham publishes REVITALIZATION.

Storm Cunningham publishes REVITALIZATION.

A former Green Beret SCUBA Medic, Storm lives in Arlington, Virginia, and is the author of two highly-acclaimed books: The Restoration Economy (Berrett-Koehler, 2002), and Rewealth (McGraw-Hill Professional, 2008). His upcoming 3rd book is RECONOMICS: (coming January 2020).

His 100+ global client list includes: US State Department, Boeing, Harvard University, Ontario Chamber of Commerce, Israel Planners Association, European Property Italian Conference, University of Guadalajara, National Arbor Day Foundation, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, American Institute of Architects, Project Management Institute, US Embassy (Poland), Governor of Montana, Canadian Urban Institute, Santee Cooper, Urban Land Institute, University of Texas, Leadership Cleveland, and many more.

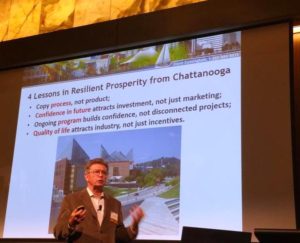

Learn more about his consulting, books, talks, and workshops at StormCunningham.com [Image: Storm keynoting conference of the Planning Institute of Australia (2015). Photo by Adam Beck.]

See full article by Ely Portillo in the Charlotte Observer.

See the Cross Charlotte Trail master plan Executive Summary (PDF).