A new analysis of reef restoration projects in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary suggests they could play a key role in helping staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) recover from being endangered. Matthew Ware of Florida State University in Tallahassee and colleagues presented these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on May 6, 2020.

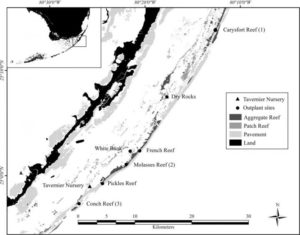

Location of the coral restoration foundation™ nursery (24.9882° N, 80.43633° W), coral outplant sites, and reef types. Reef types are from the Unified Florida Coral Reef Tract Map v2.0 (74). Carysfort (1), Molasses (2), and Conch Reefs (3) were used as examples to calculate restoration times based on NOAA Recovery Plan criteria.

A central part of this plan is outplanting, in which corals are cultivated in a protected area before being transplanted to the restoration site.

While outplanting efforts have been in place for many years, only recently has enough time passed to analyze their long-term potential.

Now, Ware and colleagues have applied photographic monitoring and in-person measurements to assess 2,419 staghorn coral colonies outplanted to 20 different sites in the Florida Keys between 2007 and 2013 by the Coral Restoration Project.

The analysis revealed that survivorship–the percentage of colonies containing living tissue–was high for the first two years after outplanting, but declined in subsequent years.

The researchers used statistical modeling to predict future survivorship, finding that 0 to 10 percent of the colonies would survive seven years post-outplanting. This means that large numbers of colonies need to be outplanted to start, so ecologically relevant numbers survive longer-term. Coral growth rates were similar to the wild population.

The authors acknowledge some limitations of their analysis, including a lack of comparison to natural populations at outplant sites, differences in colony numbers and outplant strategies among sites, and low sample sizes for some years.

Still, the findings suggest that outplanting could help restore staghorn coral populations by protecting against local extinction and maintaining genetic diversity in the wild.

Meanwhile, the same major stressors that have plagued these corals over the last few decades–disease and bleaching, both related to global warming–remain. The new findings support NOAA conclusions that mitigating these stressors is needed to achieve full, long-term recovery.

Photo of bleached staghorn coral by PublicDomainImages from Pixabay.