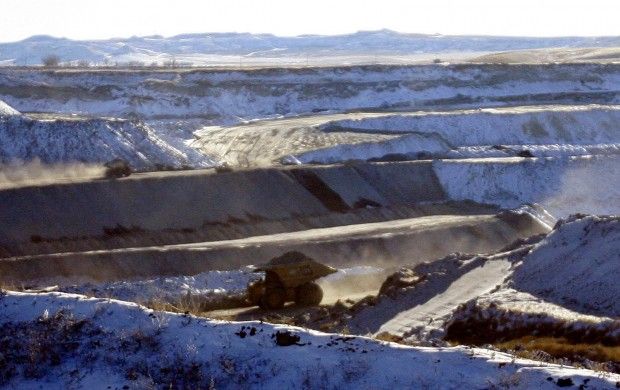

L.J. Turner gazes across a pit so massive its size is hard to fathom. Enormous draglines dredge up shiny black coal. Once, Turner grazed cattle on 6,000 acres of publicly owned grassland here. Then the land was swallowed by Peabody’s North Antelope Rochelle Mine, the world’s largest coal mine.

Thirty-some years ago, the rancher says, before mining companies turned Wyoming’s Powder River Basin into the nation’s most productive coal region, they made a promise: When they finished extracting coal, they would restore the land.

Under federal law, companies must reclaim the land they’ve mined. To ensure that cleanup is completed, they must provide financial guarantees — bonds, cash or collateral to cover the entire cost of reclamation.

Wyoming and West Virginia have much in common when it comes to coal.

As the country’s first- and second-largest producers, coal is central to their economies. Their governors are outspoken supporters of the industry. And both have been forced to grapple with the prospect that coal companies, under increasing financial stress, may no longer have the money to pay for the reclamation they once promised to complete.

But on the last point, that is where the similarities end. America’s leading coal-producing states have pursued different strategies to address the emerging challenge raised by the bankruptcy of Alpha Natural Resources. The Virginia-based firm, one of America’s largest coal companies, has unsecured reclamation obligations totaling $655 million in the two states.

West Virginian regulators struck a deal with Alpha aimed at gradually transitioning the Virginia-based coal company away from a form of reclamation insurance known as self-bonding, where firms use their own finances as collateral on future cleanup costs.

Mountain State officials notably reserved the right to object to any restructuring plan that does not replace Alpha’s self-bonds with a secured form of credit, like cash or a surety bond. The agreement also called on Alpha to immediately reduce its self-bonding obligation by $10 million and to begin reclamation work at one of its mines.

Their Wyoming counterparts say they too want to move Alpha away from self-bonds, but the Cowboy State agreement with the company contains few of the provisions called for in the West Virginia deal.

Environmentalists are skeptical. They believe Wyoming’s deal with Alpha represents a giveaway to the coal company.

On January 23, 2016 the federal Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation ordered Wyoming regulators to conduct an investigation into two bankrupt coal companies’ mining permits, saying the state may be allowing the firms to operate in violation of the law.

The orders follow the bankruptcy of two of the country’s largest coal companies, Arch Coal and Alpha Natural Resources, and comes amid growing concern they may not be able to afford their hefty reclamation obligations. The combined cost of cleaning up the two companies’ Wyoming mines is about $900 million.

See full article & photo credit.

See Grist article on the larger problem of coal mine cleanups.